Poor Edward Braddock always gets a drubbing for his mismanagement of the Monongahela Campaign. But the French and Indian War saw an equally stupid disaster perpetrated by James Abercrombie, who wasted thousands of men in a futile assault against Fort Ticonderoga in July 1758. The French position at Ticonderoga was not insurmountable. The terrain gave the British a chance to flank the fort without difficulty, while unoccupied hills nearby offered prime artillery positions. “It is rare in military history for a commander to be faced by such a range of options,” notes Geoffrey Regan, “any one of which guaranteed success.” Instead, Abercrombie opted for a suicidal frontal assault. The result was a bloodbath: 2,000 men fell, including nearly half of the famous “Black Watch” Highland regiment, and the attack was repulsed. Abercrombie lost his job to Edward Amherst, who captured Ticonderoga a year later with fewer men at a fraction of the cost.

The Crimean War (1853-1856) is the apotheosis of British military incompetence, a conflict mismanaged on every level. Presiding over it was Lord Raglan, a former aide to the Duke of Wellington completely out of his depth. “Without the military trappings,” wrote Cecil Woodham-Smith, “one would never have guessed him to be a soldier.” Raglan was an amiable man but at 65 years-old he was senile and unhealthy. On multiple occasions, he referred to the Russians as “the French,” forgetting France was now his ally. His inability to sort out differences amongst his subordinates, especially cavalry commanders Lucan and Cardigan, led to disaster in Balaclava’s infamous Charge of the Light Brigade. Raglan blundered into victory at the Alma, making assaults to capture and recapture the same ground and allowing the routed Russians to escape unhindered. His mismanagement of Balaclava turned a potential victory into an epochal gaffe; the Light Brigade’s fate hinged on his inability to articulate a clear order. His troops then hunkered into trenches before Sebastopol, dying of disease and cold from atrocious medical care and inadequate provisions. Raglan suffered along with his troops, and in 1855 died of dysentery.

“A brave man who loved action but feared responsibility for the lives of others” (Byron Farwell), Buller was Britain’s equivalent of Ambrose Burnside. Affable and well-liked, he had no business commanding an army. Early in the Boer War he lost battle after battle, never realizing infantry assaults against well-entrenched opponents rarely works. Spion Kop (January 23-24, 1900) is a representative case. Buller’s first mistake was delegating responsibility to Charles Warren, his equally incompetent second-in-command. Warren’s lead brigade smashed into the teeth of the Boer position, becoming pinned down between two Boer forces. Without entrenchment tools, artillery support or proper leadership they were forced to endure a brutal crossfire. Buller’s non-management is inexplicable. He made no effort to reinforce Warren, even calling off a flank attack that may have won the day. 1,700 troops fought while 28,000 remained idle. When Highland troops launched an unauthorized charge he angrily ordered them to withdrawal – after it succeeded! Ultimately 1,500 men died pointlessly. The bright side? Buller and Warren were finally sacked.

As Britain’s commander-in-chief in the Revolutionary War, Howe won several battles and executed one brilliant campaign. But nearly all were Pyrrhic victories, Howe winning the battlefield while forfeiting long-term advantage. Howe managed the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, winning a tactical victory only after suffering 30 percent casualties. Howe then offered a passive defense of Boston, playing cards instead of campaigning and ultimately abandoning the city without a fight. Howe redeemed himself routing George Washington’s army on Long Island and seizing New York City. Howe’s hesitance in attacking Brooklyn Heights, however, allowed Washington to escape. Worse, Howe left scattered outposts throughout New Jersey, allowing Washington easy victories at Trenton and Princeton that winter. Howe’s final blunder came during 1777’s Saratoga Campaign. John Burgoyne’s New York offensive threatened to split the colonies in two, and Howe was to join in a pincer movement against Horatio Gates’ Continentals. Howe instead marched on Philadelphia. He won a costly victory at Brandywine and captured Philadelphia but again allowed Washington to escape. Meanwhile Burgoyne was trounced by Gates and forced to surrender – an event that brought France into the war. After this debacle, Howe was finally sacked.

Sir John Fortescue described Whitelocke as “bound up indissolubly with foolish expeditions.” He spent most of his career in the West Indies, notably in Britain’s disastrous attempts to conquer Santo Domingo during Touissant L’Overture’s slave revolt. He earns his place here for mismanaging the 1807 Buenos Aires expedition, a costly sideshow of the Napoleonic Wars. Whitelocke’s troops landed outside Buenos Aires on July 1st and routed a token Spanish force. However, Whitelocke delayed following up, giving local militia time to organize. Whitelocke’s troops marched into the city, only to face a hostile citizenry. Every window housed a sniper, an artilleryman or an angry local with a pot full of boiling oil. Whitelocke exercised little control, allowing his force to be divided and attacked piecemeal in the streets. Trapped in Buenos Ares, Whitelocke capitulated to Spanish General Liniares on August 12th. He’d lost more than 3,000 of his 10,000-man force in the meantime. He was ignominiously cashiered upon returning to England.

To hear Charles Townshend tell it, he was a genius comparable to Napoleon and Clausewitz. The 43,000 troops lost during the Siege of Kut might beg to differ. Driven by ambition and overconfidence, Townshend led his 6th Indian Division into Britain’s greatest humiliation of World War I. Ordered to advance on Baghdad in September 1915, Townshend expressed private misgivings. Publicly though, he leaped at the chance for glory, dreaming himself Governor of Mesopotamia. After several initial victories, stiffening Turkish resistance and heavy casualties stopped Townshend’s advance. Ordered to withdraw to Basra, Townshend instead hunkered down in the village of Kut. Townshend’s men endured a horrific 147-day siege. Townshend made little effort to escape or prevent the Turks from surrounding him. He even forbade sorties on the grounds that “withdrawing” afterwards sapped morale! A hastily-organized relief force lost 23,000 men trying to raise the siege. His troops decimated by starvation and cholera, Townshend finally surrendered on April 29th, 1916. Townshend enjoyed a cushy captivity in Constantinople while his troops endured forced labor. The British government was so embarrassed by Kut that they censored mention of it. Townshend became a Lieutenant-General, knight and MP, but history remembers him as an arrogant boob.

When Japan entered World War II, Britain was understandably preoccupied with Nazi Germany. The Japanese overran Hong Kong, Malay and Burma in lightning campaigns. The biggest prize, however, was Singapore, the heavily-fortified port considered “the Gibraltar of the East.” Fortunately for Japan, its opponent was the singularly inept Arthur Percival. Percival apparently occupied a strong position. His 85,000 Commonwealth troops vastly outnumbered Yamashita’s 36,000 Japanese. But his men were badly overstretched, with few tanks or modern planes to oppose Yamashita. Percival’s myopic focus on a naval attack – he believed landward defenses would be “bad for the morale of troops and civilians” – ceded initiative to Yamashita, who navigated the “impassible” Malay jungle and overwhelmed the British. Percival folded with a whimper, surrendering to Yamashita in “the worst disaster in British history” (Winston Churchill). Unlike Townshend, Percival endured imprisonment just as bad as his men. Percival came out of it worse, however; he became the only Lieutenant-General in British history not to receive a knighthood.

What’s worse than surrendering an entire army? How about utterly destroying one? “A decent, proud, but stupid man” (James M. Perry), MacCarthy inherited a difficult situation as Governor of Africa’s Gold Coast. Ongoing disputes with the powerful Ashanti tribe led to war in 1824. MacCarthy mismanaged the resultant campaign in bizarrely comic fashion. MacCarthy anticipated a colonial mistake repeated by Custer, Chelmsford and Baratieri. Starting with a 6,000-man force, he divided it into four uneven columns. MacCarthy’s own force numbered a mere 500, against 10,000 Ashanti. When the Ashanti initiated battle on January 20th, the other columns were tens of miles away. At the battle’s onset, MacCarthy ordered his musicians to play God Save the King, thinking this would scare the Ashanti away. It did not. A ferocious battle ensued, MacCarthy’s troops holding their own until ammunition began running out. Hard-pressed, MacCarthy called up his reserve ammunition, only to find macaroni instead of bullets! The Ashanti overran and massacred the British force, with only 20 survivors. MacCarthy was killed, his heart eaten and head used as a fetish for years. It took 50 years of intermittent warfare to subdue the Ashanti.

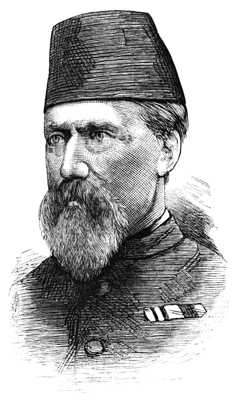

Assigned to suppress the Mahdist Uprising in the Sudan, Hicks led what Winston Churchill called “the worst Army that has ever marched to war” – a rabble of Egyptian prisoners and ex-rebels, some shipped to the front in shackles. Arrogant British officials assumed this paltry force would put the pesky Mohammedans in their place. Hicks proved them wrong. In fall 1883, Hicks marched his jerry-rigged 10,000-man army into Sudan. Misled by treacherous guides, Hicks’ army fell victim to the desert clime, losing hundreds to desertion and dehydration. On November 3rd, the Mahdists, 40,000 strong, finally pounced at the oasis of El Obeid. After two days of desperate fighting, the army was overrun and massacred, with all but 500 men killed (Hicks included). Hicks’ stupendous failure set the stage for Charles Gordon’s doomed stand at Khartoum and fifteen years of fighting in Sudan.

Britain won the Anglo-Afghan War’s first round, routing Dost Mohammed and capturing Kabul. But the Afghans hated English rule and quickly revolted. Into this firestorm stepped William Elphinstone, the only man to lose an entire British army. Riddled with gout and heart disease, Elphinstone was a poor choice to command. He arrived in Kabul in 1842, with disaster looming. British encampments were sighted lower than Kabul’s city walls, with provisions located outside them. Afghan bandits murdered Britons who ventured out of camp. Patrick Macrory characterizes Elphinstone as “[seeking] every man’s advice… he was at the mercy of the last speaker.” Fatally indecisive, he allowed Afghans to kill envoys Alexander Burns and William Macnaghten, capture his supplies and snipe at his men without response. Elphinstone finally capitulated, agreeing to withdraw his army to India. Elphinstone’s army, accompanied by thousands of camp followers, staggered through the Afghan mountains. Their numbers were whittled down by disease, cold weather and incessant Afghan attacks. In the Khyber passes, the Afghans finally massacred the survivors. A single European, Dr. Brydon, survived of 16,000 who’d left Kabul. Elphinstone himself died in Afghan captivity. Novelist George Macdonald Fraser aptly called Elphinstone “the greatest military idiot, of our own or any day.”