All things botanical remained ultra fashionable in England (less so in America) in the nineteenth century. Exotic plants were grown in hothouses, gardens were filled with flowers, and floral themed goods ranged from wallpaper to fabrics and jewelry. By 1855, pteridomania, or a craze for collecting and cultivating ferns, swept through Victorian society like chicken pox in a day care center. “Fern expeditions” to the Continent (Europe), Asia and beyond brought wild fern specimens home. In fact, so many species were removed from their native environments that some became threatened, or even went extinct. Hunting for ferns was considered thrilling and dangerous, and it continued into the early twentieth century.

In 1887, Henri Rivère created the Théâtre d’Ombres in Paris’ famous Montmartre district. Much more elaborate than today’s version – a bed sheet, a flashlight, and a hand contorted into the shape of a mutant bunny – the Théâtre d’Ombres employed a twenty-voice choir, an orchestra, and Japanese-style puppets. Contemporary accounts enthuse over the beauty of the shadow plays, which included at least one patriotic, military themed play with two acts and fifty tableaux. Eventually, Rivère would produce forty-three shadow plays until the café closed in 1897. He copied the idea of shadow theater from other people, of course. Even then, you couldn’t escape the Pirate Bay.

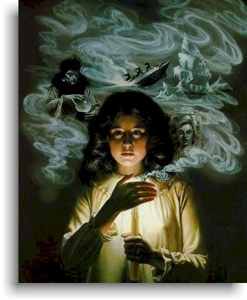

Tea leaves, palm reading, the good old crystal ball … the Victorians used all these methods and more while attempting to catch a glimpse of the future. What else did they try, you ask? Dice, apples, nuts, mirrors, candles and wax, playing cards, seeds, dreams, coins, fruit cake, moles and warts, dead people (communication with the dead through spiritual mediums was more popular than Hot Pockets at a nerd convention), all played a role in divination – and the list goes on. Many forms of divination were practiced by young women trying to find out more information about their future husbands. Seems more romantic, if less accurate, than Googling your potential spouse.

Victorians didn’t necessarily like to practice the art of taxidermy itself, but many did collect and appreciate animals of the stuffed variety. Consider the work of Walter Potter, for example, whose highly detailed anthropomorphic taxidermy tableaux included guinea pigs playing cricket, as well as cute little kittens in cute little frilly costumes getting married. Sweet, except for the fact they’re all dead, dead, dead. Allegedly of natural causes – but I have my doubts. Nevertheless, Potter’s museum in Bramber, Sussex (England) was a popular tourist attraction. Stuffed hedgehogs had delighted Victorian audiences at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and this had helped to popularize the unsavory craze. Ugh.

Did you think pr0n was invented by the Internet? Nope. Nineteenth century gentlemen had a pretty definite taste for hard-core erotic literature and photographs—sold furtively under the counter, and purchased by the gents in secret. The written erotica, mostly by that ubiquitous author, Anonymous, ranges from straightforward harem scenarios to D/S, BDSM, orgies, and fetishes in settings like a girls’ school. Magazines like the Pearl and the Oyster offered lighter fare, much like a Victorian Playboy without the pictures. And erotic photographs flourished, the new invention used to capture some very naughty goings-on, indeed. By the way, flagellation was nicknamed “the English vice.” Draw your own conclusions.

Many Victorians were avid collectors. Most specialized in one subject or another, but a select few were indiscriminate to a ridiculous degree. Their collections contained various “curiosities” such as zoological, botanical, archaeological and geological specimens, shrunken heads, seashells, antique weapons, clockwork automata, etc. Some created a “cabinet of curiosities”—in this case, cabinet meaning a room where such accumulated oddities were displayed. Far from being a new idea, such collections had been around since the seventeenth century. One of the most famous was P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York, where 15,000 patrons a day could gawk at the Feejee Mermaid, and living whales, between 1841 and 1865.

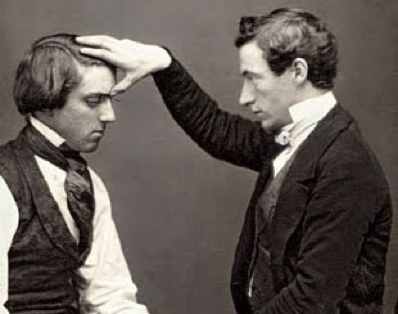

Nineteenth century folks found mesmerism—“animal magnetism” or hypnotism—utterly fascinating. Apart from providing plot fodder for a number of erotic novels, displays of mesmerism were, like now, popular entertainment. Victorian stage mesmerists didn’t make grown men cluck like chickens very often. Some demonstrated their prowess by making their subjects insensible to pain and passing surgical needles through their forearms to the delight of audiences. Ordinary people took to mesmerism to entertain their friends. One practitioner allegedly mesmerized live lobsters in a fish market, and in front of awestruck witnesses, proceeded to cut off their legs and tails with scissors. The story has it that the lobsters showed no evidence of pain – I suspect only because no one could hear their tiny, agonized screams.

Unsanitary environments, poor sanitation, bad hygiene, tainted water, adulterated food, contagious diseases, and other hazards of living in the nineteenth century made life expectancy short for the average person. Hence, lots of funerals. With the death of Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, in 1861, publicly mourning the deceased became not just a social necessity, but an event with quite elaborate rituals. Whole industries sprang up offering mourning clothes, stationary, funeral wreaths, funeral biscuits (cookies, like Goth party favors) and mourning jewelry, often made of jet or onyx and featuring the deceased’s hair. Showing the proper degree of mourning was a sport taken as seriously as the Super Bowl, but with less face painting, shirtlessness, and clowns holding John 3:16 signs.

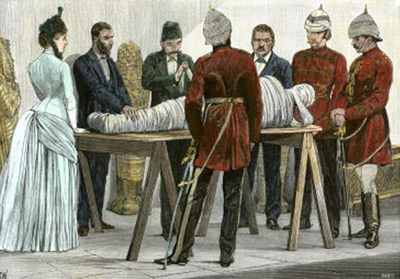

The nineteenth-century craze for all things Egyptian led naturally to an unwrapping or “unrolling” of mummies. Contrary to a popular urban legend, people didn’t do this at home. Who wanted all those bits of preserved flesh and bitumen scattered over the carpet like Ed Gein’s favorite confetti? Instead, the public attended lectures and exhibitions, where self-titled experts cut into the mummies they’d purchased at auctions. Travelers also liked to bring mummies home from their Egyptian vacations. So much so, in fact, that American newspaper accounts from the latter part of the century complained about mummies being made to order, usually from the bodies of recently deceased beggars and other poor people..

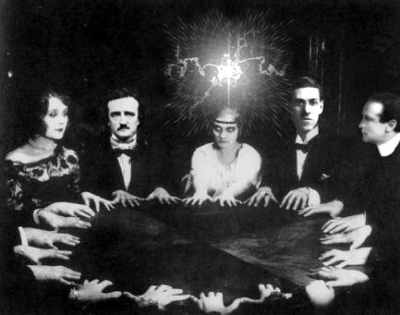

Remember I mentioned communication with the dead? The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were the heyday of spiritualism. Séances at which mediums produced phenomena like table rapping, ghost materialization, and ectoplasm were very popular. At home, people tried automatic writing and Ouija boards. Many mediums were women, as it was thought that “sensitive” females were well suited to opening themselves up to spiritual possession. And if that’s not a metaphor for something Freudian … but I digress. Of course, as soon as mediumship became a lucrative business, deliberate frauds got into the act. The escape artist and magician, Harry Houdini, exposed many fraudulent mediums. Victorians may not have had Twilight movies to look forward to (those lucky, lucky bastards), but they managed to find entertainment in some other fairly weird ways … and all without the benefit of electricity, texting, iProducts, or illegal downloading. Amazing. Read More: Facebook