This worm was trawled from the sea floor (3,900 feet/1,200 metres) off the northern coast of New Zealand this year. Yes, it may be pink; and yes, it may reflect rainbows – but polychaete worms can be ferocious predators. The “tentacles” on its head are sensory organs designed to detect prey. This one can turn its pharynx inside out in a sudden grab for smaller creatures – think Alien. Thankfully, these types of worms rarely grow longer than 10cm. They also tend to stay well out of our way, often found near hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor.

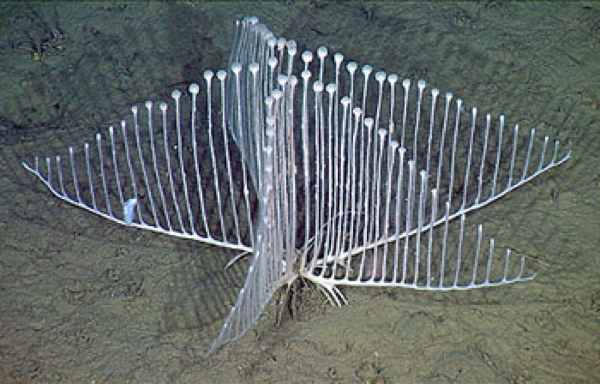

Looking rather unnervingly like a headcrab, these unique lobsters were found on the same dive that discovered the polychaete worm, but a little deeper, at around 4,600 feet/1,400 metres. Although the squat lobster was already known to science, this particular species had never before been seen. Squat lobsters live as deep as 5,000 metres, and are distinguished by their large front claws and compressed bodies. They can be detritus-feeders, algal grazers, scavengers or predators. Not much is known about this particular species, except that it was almost exclusively found near deep-sea corals. Most corals obtain nutrients from photosynthetic algae that live within the coral’s tissue. That also means that they have to live within 200ft/60m of the surface. Well, not this species, also known as the harp sponge. It was discovered in 2000 off the coast of California, but only confirmed to be carnivorous this year. Shaped somewhat like a candelabra to increase its surface area, it traps tiny crustaceans with tiny Velcro-like hooks and then spreads a membrane over it, slowly digesting it with chemicals. As if that wasn’t weird enough, it reproduces using “sperm packets” – see those balls at the top of each branch? Yes, those are packets of spermatophores, and every now and then they float away to find another sponge and reproduce. This handsome fellow is a species of tonguefish, which are usually found in shallow estuaries or tropical oceans. This one lives in the deep sea, and was trawled from the bottom of the western Pacific earlier this year. Interestingly, some tonguefish have been spotted around sulphur-spewing hydrothermal vents, but scientists are unsure of the mechanism that allows this species to survive the conditions there. Like all bottom-dwelling tonguefish, both of it eyes appear on one side of its head. Unlike many tonguefish, however, they happen to look exactly like googly eyes from a golliwog. The goblin shark is a really strange creature. In 1985, it was discovered in the waters off eastern Australia. In 2003, more than a hundred were caught off north-eastern Taiwan (reportedly after an earthquake). However, apart from sporadic sightings of this nature, little is known about this unique shark. It is a deep-sea, slow moving species that can grow to be 3.8 metres long (or longer! That’s only the largest one we know about). Like other sharks it can sense animals with electro-sensitive organs, and possesses several rows of teeth, but in the goblin shark some are adapted for catching prey and others for crushing crustacean shells. If you are interested in seeing how it captures prey with that mouth, you can watch this video. And try to imagine a nearly 4m long shark coming at you with those jaws! Thank goodness they (usually) live so deep.

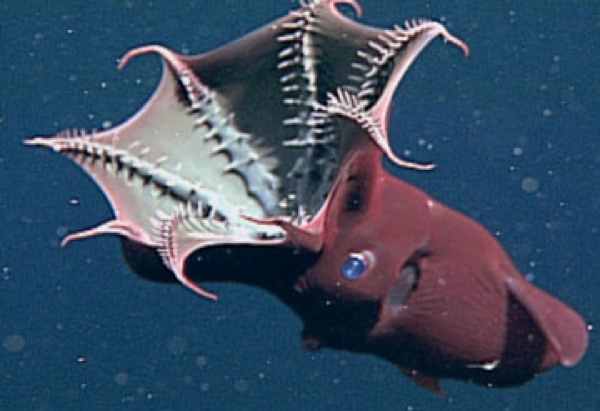

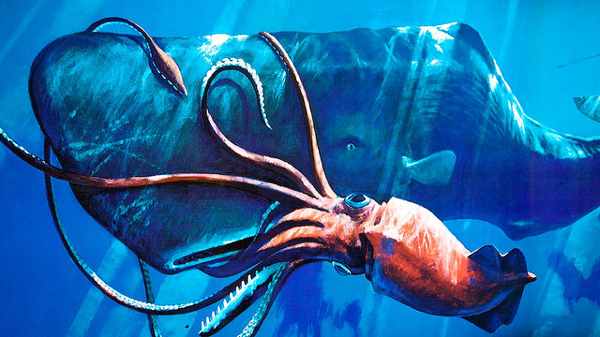

The brightly coloured specimen above (the colours are somewhat useless when you live where light can’t penetrate) is a member of the unhappily-named “flabby whalefish” species. It was trawled off the east coast of New Zealand, at a depth of more than 2 kilometres (1.3 miles). At the bottom of that deep blue sea, they did not expect to find many fish – and in fact it appears that the flabby whalefish has little company. This family of fish has been found as deep as 3,500 metres; has small eyes – they are pretty useless in this environment after all – and instead the fish tend to have a very well developed lateral line to detect vibrations. It also lacks any ribs, which is perhaps why it appears so “flabby”. First seen in 1999 and then videoed in 2009, this cute animal (for an octopus, anyway) can live as deep as 7,000 metres below the surface, making it the deepest-dwelling octopus species on record. Named for the flaps on either side of its bell-shaped head, this group of animals – there may be as many as 37 species – never sees the sunlight. The dumbo octopus can hover above the seabed with a type of siphon-based jet propulsion, where it feeds off of the snails, bivalves, crustaceans and copepods that live there. The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis, literally: vampire squid from Hell) is actually more beautiful than hellish, I think. This squid does not live at the same depths as the number one entry on this list, but at 600-900 metres, it still dwells a long way down as far as squid are concerned. At the upper levels of its range, there is some sunlight, and as a consequence it has evolved the biggest eyes of any animal (in proportion to size) in order to capture as much light as it can. What is really fascinating about this animal are its defense mechanisms. In the dark seas that it lives in, it releases bioluminescent ‘ink’ that dazzles and confuses other animals while it escapes. And check out this cool video, where a vampire squid turns itself ‘inside out’ to avoid predators: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWAnliNc6wk. This works a bit better when the sea around it is not illuminated. Normally, it can emit a bluish light which, seen from underneath, helps to camouflage; but when spotted, it wraps itself with its black-coloured underside… and disappears. Found deep off the coast of California in 2009, this mysterious shark belongs to the group of animals known as chimaeras, which may be the oldest group of fish alive today. Some believe that these animals branched away from sharks about 400 million years ago, and survived by living at such great depths. This particular ghost shark uses its fins to ‘fly’ through the water, and the male has a spiky, club like, retractable sexual organ that protrudes from its forehead. It might be used to stimulate the female or to pull her closer, but we don’t know enough about these animals to be sure. The colossal squid truly deserves its name, growing to lengths of between 12-14m (39-46 feet) – about the size of a bus. It was first “discovered” in 1925 – but only its tentacles were found, within the belly of a sperm whale. The first complete specimen was found near the surface in 2003. In 2007, the largest known specimen (10m) was captured in the Antarctic waters of the Ross Sea, and is now on display in the national museum of New Zealand. It is thought that the squid is a slow-moving ambush predator, feeding on large fish and other squid after attracting them with bioluminescence. Frighteningly, Sperm whales have been observed with scars that are believed to have been caused by the swivelling hooks on a colossal squid’s tentacles. Weird, new species of deep-sea jellyfish? Maybe a floating whale placenta, or a piece of garbage? Until earlier this year, nobody knew. Speculation reached fever-pitch after this video went viral on YouTube – but marine biologists have since identified it as a type of jellyfish, known as a Deepstaria enigmatica.