These 10 films are a mix of both. Although these directors might not have been at the peak of their talents, their early movies still stack up among their best work. The following films affirm the adage: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. 15 Great Movies From Directors Under 30

10 Bad Taste (1987)

Director: Peter Jackson

With The Lord of the Rings franchise, Peter Jackson is a modern master of fantasy. His films epically rendered J.R.R. Tolkien’s mythic story with a remarkable eye for detail. Every element of Frodo’s adventure was individually crafted to serve the story. On a fraction of the Rings budget, Jackson told another story just as entertaining.[1] Bad Taste is a schlocky science fiction movie. A group of aliens invade New Zealand to harvest humans to serve as the meat in an intergalactic fast-food franchise. Made for only $25,000, the film saved money by casting Jackson and his friends as most of the characters. The rest of the cash went into hilarious displays of body horror. Chunks of brains drip out of people’s skulls. Intestines explode with slapstick-like glee. Bad Taste is not a deep film by any means. It is mostly an exercise in reveling in destroying man-eating aliens with chainsaws or rocket launchers. Yet there is a charm in that kind of B-movie nonsense.

9 This Is The Life (2008)

Director: Ava DuVernay

Ava DuVernay’s movies are always grounded in reality. With Selma, When They See Us, and 13th, DuVernay has consistently drawn upon African-American history to find a compelling story. This instinct was first honed in This Is the Life. If This Is the Life is to be believed, hip-hop all but evolved out of one building, Los Angeles’ Good Life Cafe (aka Good Life Health Food Centre). Before expressing herself as a director, DuVernay regularly attended the cafe’s open mic sessions. There, she rubbed elbows with many burgeoning rappers. In the early 1990s, future all-stars like Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, will.i.am, Common, and Lenny Kravitz cut their teeth at the open mics. The venue provided these up-and-coming talents with an outlet to sharpen their skills. Told from the vantage point of someone who witnessed it firsthand, the documentary is a personal recollection of one of the most important artistic explosions of the last half of the 20th century.[2]

8 Pushing Hands (1991)

Director: Ang Lee

In the West, Ang Lee is best known for spectacle. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; Hulk; and Life of Pi were visually transformative movies that pushed the boundaries of special effects. Yet Ang Lee wishes that this was not his legacy. He prefers his earlier intimate work in Taiwan. In their own way, those films are just as impactful. Pushing Hands was cowritten with Ang’s regular partner James Schamus. The film deals with the central question in many future Ang Lee projects—the conflict between family and duty. In Pushing Hands, Sihung Lung plays Mr. Chu, a retired tai chi master. Together with his son, Alex (Bo Z. Wang), Mr. Chu leaves China for America. In a classic take on the fish-out-of-water story, the traditional Chinese father struggles to adjust to American life, creating a wedge in the family. The put-upon son is torn between his duties to his father and his wife (Deb Snyder). Lee’s deft handling prevents the nuanced story from devolving into caricature. Comedic moments are undercut with legitimately harrowing scenes. It is a touching meditation on what we owe to each other. Lee and Sihung Lung further explored the theme in the later films The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman. These three films make up the pseudo trilogy Father Knows Best.[3]

7 Hard Eight (1996)

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Among all of Paul Thomas Anderson’s movies, Hard Eight is distinct. It is the only one that feels like it could have been made by somebody else. Even with the wave of thrillers that exploded in the 1990s, Hard Eight still stands as a dark portrait of the follies of gambling. Outside of being a tightly told story of the corrosive nature of greed, the movie interestingly showcases the director trying to discover his voice.[4] In Hard Eight, Anderson honed many of the elements that would define his later films. Calling cards like narrative twists, idiosyncratic characters, and the cruelty of coincidence first emerged. The movie featured three actors to whom Anderson would return for most of his career. The bulk of the story follows Philip Baker Hall as Sydney, a gambler in his sixties, and John C. Reilly as John, Sydney’s protege. Another one of Anderson’s muses, Philip Seymour Hoffman, makes a brief appearance. Hard Eight also launched the partnership of Anderson mainstays Robert Elswit and Jon Brion behind the camera. For both the characters and the director, Hard Eight was a movie about finding identity. Within a few years, Anderson was set on one of the most unique filmographies of the millennium.

6 I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978)

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Universal Pictures did not want Robert Zemeckis to make this movie. The 26-year-old upstart only got the job because Hollywood’s wunderkind Steven Spielberg believed in him. Spielberg assuaged the studio’s fears by promising to take over directing if Zemeckis stumbled. Spielberg never got the chance. Instead, Zemeckis fell upon the winning formula of his career: nostalgia.[5] Like Marty McFly in Back to the Future or Forrest Gump in the eponymous movie, the characters in I Wanna Hold Your Hand serendipitously shape some of the greatest moments in history. The movie follows a group of six New Jersey teenagers as they try to score tickets to The Beatles’ imminent debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. Enraptured by the band, the gang goes to absurd lengths to see their idols. The film toys with the truth to a hilarious degree. As with Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Zemeckis turned a love letter to icons of 20th-century pop culture into a delightful romp. Though the director achieved greater success later, his first film remains his most unabashedly earnest tribute to the past. 10 Little-Seen Films by Great Directors

5 Medicine For Melancholy (2008)

Director: Barry Jenkins

Ostensibly, Medicine For Melancholy is a romance. Trailing two potentials suitors walking around town after they have a one-night stand, the film convincingly argues that love can blossom from a single encounter. However, this is not a traditional meet-cute. By the movie’s end, there is no guarantee that the couple will ever see each other again, let alone run off together. The whole film simply presents two people enjoying each other’s company while unsure of what will happen next.[6] Genre limitations never undercut the broader themes of the work. Most of the film deals with the interplay between race and navigating the dating scene. Like the relationship itself, Medicine For Melancholy leaves many questions unresolved. The movie works solely because it feels so genuine, practically natural. To much greater acclaim, Jenkins’s next film again struck the emotional balance between societal contemplations and budding love. That film, Moonlight, landed him a Best Picture winner at the Oscars.

4 Targets (1968)

Director: Peter Bogdanovich

On a technical level, the first film directed by Peter Bogdanovich was Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. However, that movie was so bad that Bogdanovich refused to put his name on it. He hid behind the pseudonym Derek Thomas. Instead, he decided that the first movie to bear his name would be Targets. He made the right choice. Targets is a fascinating harbinger of the future of horror as well as an ode to the genre’s past. In his last starring role, Boris Karloff is perfectly cast as an aging horror actor bemoaning the collapse of the traditional movie monster. This story is told parallel to Tim O’Kelly’s performance as a young man on a murderous spree with a rifle. The two tales eventually converge as Karloff confronts the assassin at a drive-in theater that is screening one of his films. In the movie, Karloff is victorious. In reality, O’Kelly won in the long term.[7] Released in the aftermath of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the film initially flopped. In subsequent decades, it has been reappraised. Now the film is celebrated as one of the earliest templates for the slasher trope that dominated horror in the years to come.

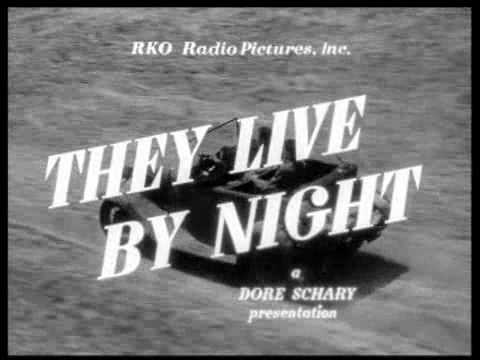

3 They Live By Night (1948)

Director: Nicholas Ray

It takes a certain level of talent to create a new genre on your first try. Though firmly indebted to noir, They Live by Night is now seen as a precursor to the trope of two lovers on the run.[8] Based on Edward Anderson’s novel Thieves Like Us, the movie introduced the now-familiar cliche of an innocent woman (Cathy O’Donnell) enticed into the criminal lifestyle by a seductive fugitive (Farley Granger). The film’s structure directly inspired Arthur Penn’s innovative Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 and Robert Altman’s Thieves Like Us in 1974. Altman’s film was also based on Anderson’s book. Even if it did not result in legions of imitators, They Live By Night remains a stirring meditation on life on the edge. Instead of over-the-top bloodshed, the film wallows in the existential dread of having no refuge. Seven years later, Ray’s allegiance to the misunderstood reached its apex with the immortally profound Rebel Without a Cause.

2 The Connection (1961)

Director: Shirley Clarke

Few movies have been as divisive upon release as The Connection. Everyone who saw it had a strong opinion. However, after two showings, police arrested the projectionist and shut down the theater. The Connection became infamous in art house cinemas as one of the most forbidden films ever. By today’s standards, it is relatively tame.[9] The Connection shocked audiences with its subject matter and delivery. Based on the play with the same name by Jack Gelber, The Connection portrays a group of jazz musicians and drug addicts as they monologize while waiting for their latest fix. Frank about the perils of heroin abuse, the movie was filled with profanity, which was considered Clarke’s most scandalous decision by early 1960s standards. Equally as innovative, the jazz soundtrack captured the emotion of the kinetic, avant-garde storytelling. Only a handful of people saw the movie upon release. They credit it as being one of the most influential movies of all time.

1 Ascenseur Pour L’echafaud (1958)

Director: Louis Malle

Ascenseur pour l’echafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) was the first crest of the French New Wave. All the key elements of the movement—convoluted plots, close-up cinematography, and tight editing—were pioneered by the 24-year-old Malle. The story structure of teenage lovers and a perfect murder plot gone awry became standard fare for the genre. Along with technical achievements, Ascenseur pour l’echafaud catapulted Jeanne Moreau to the position of major movie star.[10] Perhaps no aspect of the film better established the look and feel of French New Wave than the still-iconic soundtrack by Miles Davis. The jazz legend improvised a score after only hearing the plot. The songs were synced to the scenes later. The resulting soundtrack laid the groundwork for modal jazz’s takeover in the early 1960s. Ascenseur pour l’echafaud changed film history in both sight and sound. 10 Early Versions Of Famous Works Of Film About The Author: This is not Nate Yungman’s debut. He has written plenty on Twitter if you want to follow him @nateyungman. If you want to write to him, you can contact him at [email protected].