See Also: 10 Ways The History Of Thanksgiving Is Nothing Like You Imagined Pretty much everything American children were taught about the first Thanksgiving is a lie. That’s not to say the teachers of America were lying to their students—they were taught the same lies when they went to school. Sadly, history is often told in a different light than what actually happened centuries ago, and because of this, what we know of Thanksgiving today is mostly a myth. The holiday is celebrated every year in the United States, and many other countries have their own Thanksgiving celebrations, but how much do you really know about the first one? There wasn’t even a United States when it happened, so why do we celebrate it now? There are a ton of interesting facts about that celebration, but these are some of the most fascinating you probably believed to be true.

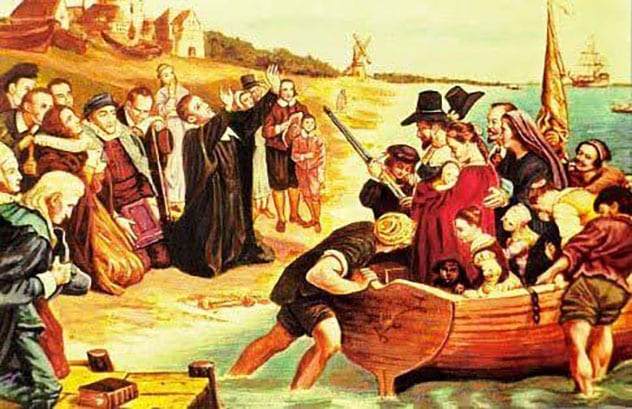

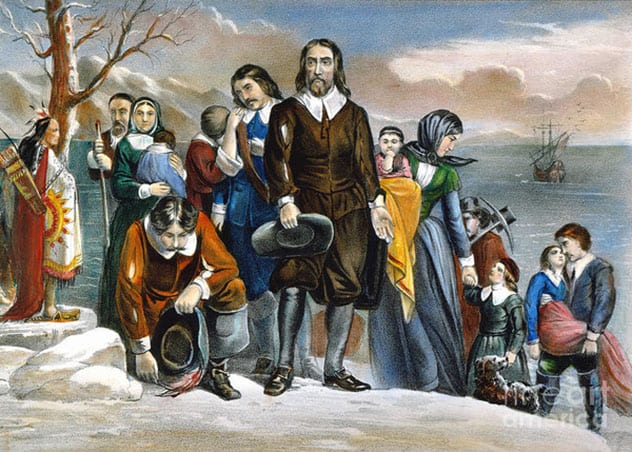

10The Pilgrims Left England For The New World

For starters, nobody on the Mayflower, or at the first Thanksgiving, called themselves a Pilgrim. That name wasn’t associated with the European settlers until the late 19th century. The Pilgrims, as we call them today, referred to themselves as either Brownists, Saints, or, more commonly, Separatists due to their disagreements with the teachings of the Church of England. Their reason for leaving their homeland centered around their belief that the Church of England violated the biblical precepts of true Christians. Because the Church of England was the law of the land in their native England, the Separatists were forced to flee or face accusations of treason. The Separatists didn’t initially flee England for the New World either. When several of their congregational leaders were executed, many of them fled England for Holland. They remained in the area for a decade before issues with aging and unemployment threatened their sustainability. Eventually, the congregation successfully petitioned for a land grant north of the Virginia territory, which they would call New England. They joined others fleeing England and set sail in September of 1620 with 102 passengers eager to settle the New World. By December, they had arrived and began to settle an area formerly called Patuxet, which they named Plymouth.[1]

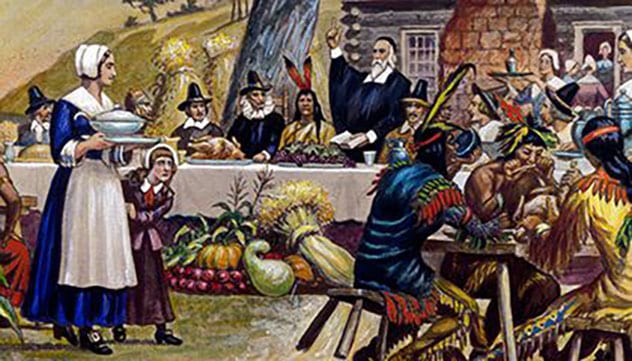

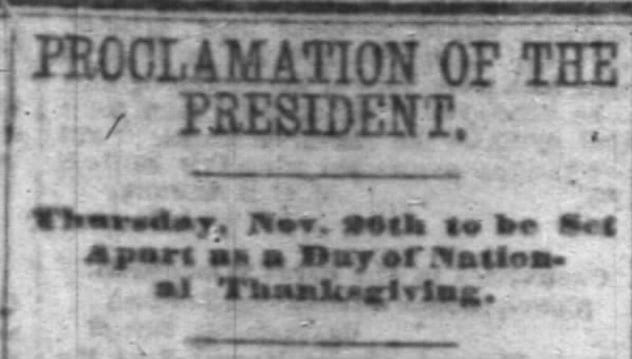

9 The First Thanksgiving Was Called “Thanksgiving”

When people refer to the first Thanksgiving in the autumn of 1621, they are getting something wrong about that feast. For one thing, the Pilgrims didn’t think of it as a “Thanksgiving” in the traditional sense, nor would they have called it that. Back in the 17th century, the settlers considered a Thanksgiving to be a solemn religious day, which revolved around a group of people gathered around to pray as a community. There were some elements of the feast that could be ascribed to a puritanical Thanksgiving, but nobody there, or even in that time period, would have referred to it as such. The autumn feast took place over three days, and it didn’t become a holiday for another 200+ years. Because Thanksgiving was previously a religious holiday, it was celebrated at different times in different places. It took a formal proclamation from President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 to establish the final Thursday in November as an American Thanksgiving holiday. This was during the height of the American Civil War, and his proclamation was written with the goal of unifying Lincoln’s “fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands.”[2]

8 The First Thanksgiving Was The First Thanksgiving

When people looked back upon the harvest celebration held in 1621, they decided it was reminiscent of their own Thanksgiving celebrations. For this reason, they retroactively called the 1621 event the first Thanksgiving, but it was neither the first nor was it truly a Thanksgiving celebration. The settlers and the Wampanoags gathered together to feast in what is traditionally called a harvest celebration, and it wasn’t unique to either culture. The Native Americans had been holding celebrations of the harvest for centuries, as had the English and many other cultures around the world. Another misconception regarding Thanksgiving has to do when it occurred. Hardly any culture celebrates the harvest in November, but that’s when Thanksgiving is held in the United States each and every year. The 1621 harvest celebration probably took place in September, or possibly early October, but certainly not as late as November. The Pilgrims offered up their harvested crops, consisting almost entirely of vegetables. The holiday was informally established in November by President George Washington in 1789, but it remained unofficial until Lincoln declared it a Federal holiday almost a century later.[3]

7 It’s All About Turkey

Modern Thanksgiving meals aren’t complete without the traditional centerpiece dish: a beautiful turkey. The bird can be roasted, fried, and even stuffed with a duck, but whichever method you and your family might go with, there absolutely has to be a turkey—Tofurky’s don’t count! It is unlikely that turkey was served at the first Thanksgiving, as the Pilgrims lacked an oven. There isn’t much known about what the Colonists did eat that day, but what is known is that the Native Americans brought five deer, but no turkeys. The presence of venison is known, thanks to the plethora of letters describing it, as deer was illegal to hunt at the time in England. It’s certainly possible that they ate turkey, but despite the birds being common in the area at the time, there’s no historical evidence it was included in the feast. There are tons of other foods commonly associated with Thanksgiving today that were certainly not at the first feast. There were no apples, pears, sweet potatoes, potatoes, or pie since they lacked flour and butter. Turkey entered into Thanksgiving celebrations when Lincoln made it a holiday. Prior to that proclamation, neither the bird nor the pilgrims were part of anyone’s Thanksgiving celebrations. In 1863, New England’s cuisine began influencing the rest of the country, and from that point forward, Thanksgiving meals required the annual sacrifice of the unfortunate, yet tasty birds.[4]

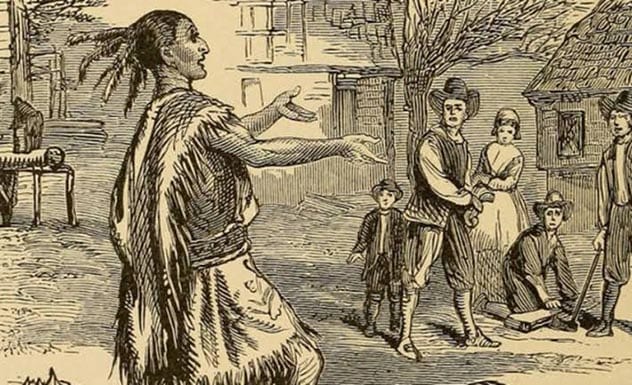

6 Native Americans Were Invited Guests

One of the most prominent aspects of any Thanksgiving story involves the attendance of around 90 Wampanoag Native Americans. In almost every account—especially in early childhood education—the Colonists invited the local tribe to celebrate with them. This was done to show unity and be neighborly, but it was mostly to offer thanks to the natives who taught the Pilgrims how to plant and harvest the local crops. There is some truth, and a little fiction sprinkled in these tales; there were around 90 Natives in attendance, and they were welcomed to join in the festivities, but there’s no indication they were invited by the Pilgrims. History being what it is, there are conflicting stories describing what truly took place during the feast. “Some accounts suggest that about 90 Wampanoag heard the settlers firing guns and came to see the cause of the stir or even ready to enter battle.” Whatever their reason for showing up, they were welcomed by the settlers with open arms. It’s possible Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag, was there to make a diplomatic call, but this is also unconfirmed, though it’s clear that nothing in the historical record describes an invitation of any kind.[5]

5 The First Thanksgiving Was A Celebration Of Friendship

When we gather around the table each November to celebrate Thanksgiving, most families describe what they’re thankful for that year. It’s possible that the colonists did the same thing, but in reality, the celebration of the harvest was likely a solemn affair. When they first arrived in the New World, the passengers aboard the Mayflower remained on the ship through the harsh winter. Half of them died, but more than that, of the 19 women who boarded the Mayflower, only five survived the brutal winter. The Wampanoags eventually helped the settlers survive by teaching them how to hunt local game, fish their waters, and grow corn, beans, and squash. They were able to communicate through an English-speaking Abenaki named Samoset, who helped broker an alliance with the local tribe. There was definitely a lot to be thankful for during the festivities, but with half of their people gone, it’s likely the people were mostly somber and thankful to be alive. One thing that’s certain, though, it wasn’t a celebration regarding the friendship between the Natives and the Pilgrims; rather, their inclusion was mostly serendipitous.[6]

4 The Pilgrims Wore All-Black And Had Buckles All Over The Place

In just about every depiction of the first Thanksgiving, and really any depiction of the people we call Pilgrims, they are wearing black clothing adorned with buckles on their hats, belts, and shoes. This depiction of Pilgrims isn’t entirely accurate, and it may have stemmed from the Victorian romanticization of the period some 200 years later. The all-black look seems to be pinned to their puritanical nature, but it couldn’t be further from the truth. Women in Pilgrim society wore a long-sleeve white undergarment, which was worn beneath a petticoat and dress, which typically was colored anything from violet to green, blue, red, or any colored cloth the ladies could get at the time. Men’s outfits generally consisted of a white collared shirt, which was worn beneath a doublet. The doublet could be black, but it could also be blue, brown, or a similar dark color. The pants would be worn as either breeches or drawers and knee-length colored stockings. The shoes were low or high-cut leather boots, typically brown in color. Other than wearing bright, colorful clothing, the most prominent feature of modern depictions of Pilgrims, the buckle, was nowhere to be seen. Some men may have had buckles on their belts (if they wore one), but they weren’t affixed to their hats, nor were they found on their shoes.[7]

3 The First Thanksgiving Was Held In A Grand Log Cabin

When the Pilgrims and Native Americans sat down to break bread for the so-called first Thanksgiving, they did so outside. There are tons of illustrations of the party enjoying a feast inside or in front of a log cabin, but log cabins didn’t exist in the 17th century, at least, the English had never heard of them, and there was no record of them existing until the 1770s. If you go to visit Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts today, you will see exactly what the Pilgrims resided in while they were establishing their colony, and it wasn’t made up of log cabins. The Pilgrims mastered the building of wooden clapboard houses made from sawed lumber. The rooves consisted of thatching, which was packed tightly to keep out the sun, wind, and rain. They used cut grasses and reeds from the local marshes, bundled them together, and layered them on the roof. Similarly, they made the walls of a framework of small sticks called wattle. They used mortar consisting of clay, mud, and grass, which they shoved into the wattle to create a smooth plaster-like wall similar to sheetrock in modern homes. As to the first Thanksgiving’s eating arrangements, they had tables outside where they enjoyed a meal alongside the Native Americans.[8]

2 The Pilgrims Were A Zealous And Overtly Religious Group

These days, we think of the Pilgrims as a puritanical society of highly conservative people, but that type of Puritanical lifestyle is better attributed to the Puritans of the 19th century. Back in the 17th century, the Puritans weren’t anything like that, and depictions of them as some sort of religious cult who never engaged in anything fun are far from the reality of their lifestyle. “The Sabbatarian, antiliquor, and antisex attitudes usually attributed to the Puritans are a nineteenth-century addition to the much more moderate and wholesome view of life’s evils held by the early settlers of New England.” Life for the Pilgrims was difficult and required a lot of work, but that doesn’t mean they couldn’t have some fun. They weren’t against marital copulation as some depictions have attested, nor were they clothed in drab outfits all the time. They enjoyed singing and dancing whenever the time allowed, and when things went well, they held a feast, and it’s that tradition that ensured the Puritans of the 17th century remain a part of the modern Thanksgiving tradition. They may not have looked or acted in the ways we believe today, but they did love a good party whenever possible.[9]

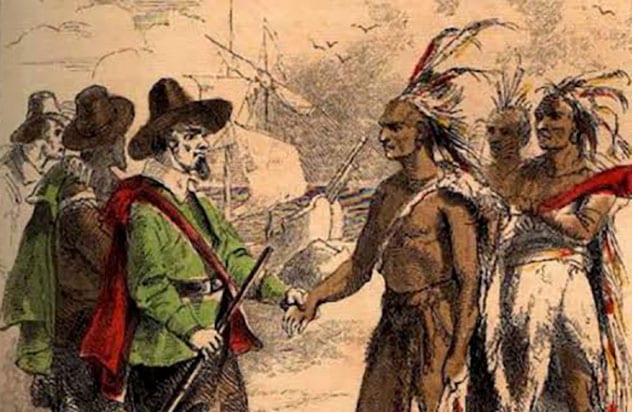

1 The Pilgrims United At Thanksgiving After A Series Of Conflicts

There’s no denying that the Native American Wampanoag Tribe suffered in the years following the first Thanksgiving, but modern interpretations and media descriptions of the event have refused to shine anything but a negative light on their relationship. Yes, they later engaged in the Pequot War, but prior to that conflict, the Pilgrims and Native Americans had a peaceful time living near one another. Members of the Wampanoag helped the Pilgrims construct their homes, and they even showed them the best places to catch fish, which is how cod landed on the menu at their three-day feast we now think of as the first Thanksgiving. Not only did the Pilgrims and Wampanoags not fight one another in the early 1620s, they had a peace treaty. The Wampanoag leader, Ousamequin (He was known as Massasoit to the Pilgrims) negotiated a peace treaty with several key points: neither party would harm members of the other, if any items were stolen, it would be returned with their own people handling punishment, weapons would be left behind when they met for any reason, and they would serve as the others’ allies during a time of war. Eventually, the peace was broken, but it was in place before, during, and for many years after the first Thanksgiving.[10] Read More: Twitter Facebook Fiverr JonathanKantor.com