We have all some experience of a feeling, that comes over us occasionally, of what we are saying and doing having been said and done before, in a remote time – of our having been surrounded, dim ages ago, by the same faces, objects, and circumstances – of our knowing perfectly what will be said next, as if we suddenly remember it! — Charles Dickens

Déjà vu is the experience of being certain that you have experienced or seen a new situation previously – you feel as though the event has already happened or is repeating itself. The experience is usually accompanied by a strong sense of familiarity and a sense of eeriness, strangeness, or weirdness. The “previous” experience is usually attributed to a dream, but sometimes there is a firm sense that it has truly occurred in the past.

Déjà vécu (pronounced vay-koo) is what most people are experiencing when they think they are experiencing deja vu. Déjà vu is the sense of having seen something before, whereas déjà vécu is the experience of having seen an event before, but in great detail – such as recognizing smells and sounds. This is also usually accompanied by a very strong feeling of knowing what is going to come next. In my own experience of this, I have not only known what was going to come next, but have been able to tell those around me what is going to come next – and I am right. This is a very eerie and unexplainable sensation.

Déjà visité is a less common experience and it involves an uncanny knowledge of a new place. For example, you may know your way around a a new town or a landscape despite having never been there, and knowing that it is impossible for you to have this knowledge. Déjà visité is about spatial and geographical relationships, while déjà vécu is about temporal occurrences. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about an experience of this in his book “Our Old Home” in which he visited a ruined castle and had a full knowledge of its layout. He was later able to trace the experience to a poem he had read many years early by Alexander Pope in which the castle was accurately described.

Déjà senti is the phenomenon of having “already felt” something. This is exclusively a mental phenomenon and seldom remains in your memory afterwards. In the words of a person having experienced it: “What is occupying the attention is what has occupied it before, and indeed has been familiar, but has been forgotten for a time, and now is recovered with a slight sense of satisfaction as if it had been sought for. The recollection is always started by another person’s voice, or by my own verbalized thought, or by what I am reading and mentally verbalize; and I think that during the abnormal state I generally verbalize some such phrase of simple recognition as ‘Oh yes—I see’, ‘Of course—I remember’, etc., but a minute or two later I can recollect neither the words nor the verbalized thought which gave rise to the recollection. I only find strongly that they resemble what I have felt before under similar abnormal conditions.” You could think of it as the feeling of having just spoken, but realizing that you, in fact, didn’t utter a word.

Jamais vu (never seen) describes a familiar situation which is not recognized. It is often considered to be the opposite of déjà vu and it involves a sense of eeriness. The observer does not recognize the situation despite knowing rationally that they have been there before. It is commonly explained as when a person momentarily doesn’t recognize a person, word, or place that they know. Chris Moulin, of Leeds University, asked 92 volunteers to write out “door” 30 times in 60 seconds. He reported that 68 per cent of his guinea pigs showed symptoms of jamais vu, such as beginning to doubt that “door” was a real word. This has lead him to believe that jamais vu may be a symptom of brain fatigue.

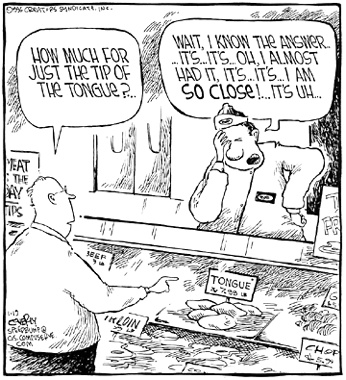

Presque vu is very similar to the “tip of the tongue” sensation – it is the strong feeling that you are about to experience an epiphany – though the epiphany seldom comes. The term “presque vu” means “almost seen”. The sensation of presque vu can be very disorienting and distracting.

L’esprit de l’escalier (stairway wit) is the sense of thinking of a clever comeback when it is too late. The phrase can be used to describe a riposte to an insult, or any witty, clever remark that comes to mind too late to be useful—when one is on the “staircase” leaving the scene. The German word treppenwitz is used to express the same idea. The closest phrase in English to describe this situation is “being wise after the event”. The phenomenon is usually accompanied by a feeling of regret at having not thought of the riposte when it was most needed or suitable.

Capgras delusion is the phenomenon in which a person believes that a close friend or family member has been replaced by an identical looking impostor. This could be tied in to the old belief that babies were stolen and replaced by changelings in medieval folklore, as well as the modern idea of aliens taking over the bodies of people on earth to live amongst us for reasons unknown. This delusion is most common in people with schizophrenia but it can occur in other disorders.

Fregoli delusion is a rare brain phenomenon in which a person holds the belief that different people are, in fact, the same person in a variety of disguises. It is often associated with paranoia and the belief that the person in disguise is trying to persecute them. The condition is named after the Italian actor Leopoldo Fregoli who was renowned for his ability to make quick changes of appearance during his stage act. It was first reported in 1927 in the case study of a 27-year-old woman who believed she was being persecuted by two actors whom she often went to see at the theatre. She believed that these people “pursued her closely, taking the form of people she knows or meets”.

Prosopagnosia is a phenomenon in which a person is unable to recognize faces of people or objects that they should know. People experiencing this disorder are usually able to use their other senses to recognize people – such as a person’s perfume, the shape or style of their hair, the sound of their voice, or even their gait. A classic case of this disorder was presented in the 1998 book (and later Opera by Michael Nyman) called “The man who mistook his wife for a hat”. Read More: Twitter Facebook YouTube Instagram