Government officials have enacted shocking policies and medical procedures. We can now look back upon some of these moments and wonder what exactly our ancestors were thinking? Many of these ideas were developed in a time when racial and female segregation was a problem, and the accepted social behavior was different from what we experience today. This article will be examining ten shocking beliefs and diagnosis that were developed during modern history.

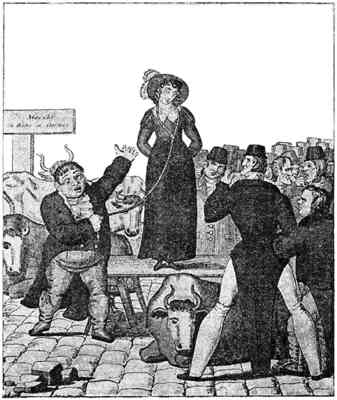

During medieval times, women were completely subordinated to their husbands. After marriage, the husband and wife became one legal entity, a legal status known as coverture. During this time in history, married women could not own property in their own right, and were, indeed, themselves the property of their husbands. It is unclear when the ritualized custom of selling a wife by public auction first began, but written records indicate it was some time towards the end of the 17th century. In most reports, the sale was announced in advance, perhaps by advertisement in a local newspaper. It usually took the form of an auction, often at a local market, to which the wife would be led by a halter (usually a rope) looped around her neck, arm or waist. The woman was then auctioned off to the highest bidder and would join her new husband after the sale was complete. Wife selling was a regular occurrence during the 18th and 19th centuries, and it acted as a way for a man to end an unsatisfactory marriage. In most cases, a public divorce was not an option for common people. In 1690, a law was enforced that required a couple to submit an application to parliament for a divorce certificate. This was an expensive and time consuming process. The custom of wife selling had no basis in English law and often resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards. However, the attitude of the authorities was passive. It should be noted that some 19th century wives objected to their sale, but records of 18th century women resisting are non-existent. In some cases, the wife arranged for her own sale, and even provided the money to buy her way out of the marriage. Wife selling persisted in some form until the early 20th century. In 1913, a woman claimed in a Leeds police court that she had been sold to one of her husband’s workmates for £1. This is one of the last reported cases of a wife sale in England. Today, you can visit a number of websites and get an online divorce.

The tobacco smoke enema was a medical procedure that was widely used in western medicine, during the turn of the 19th century. The treatment included an insufflation of tobacco smoke into the patient’s rectum by enema. The agricultural product of tobacco was recognized as a medicine soon after it was first imported from the New World. During this time, tobacco smoke was widely used by western medical practitioners as a tool against many ailments, including headaches, respiratory failure, stomach cramps, colds and drowsiness. The idea to apply tobacco smoke with an enema was a technique appropriated from the North American Indians. It was believed that the procedure could treat gut pain, and attempts were often made to resuscitate victims of near drowning. Many medical journals from this time noted that the human body can undergo a stimulation of respiration through the introduction of tobacco smoke by a rectal tube. In fact, by the turn of the 19th century, tobacco smoke enemas had become an established practice in western medicine. The treatment was considered by Humane Societies to be as important as artificial respiration. Meaning, if you stopped breathing, the doctor’s first action was to shove a tube up your rectum and to begin pumping tobacco smoke in your body. Tobacco enemas were used to treat hernias and the smoke was often supplemented with other substances, including chicken broth. According to a report from 1835, tobacco enemas were used successfully to treat cholera during the “stage of collapse”. Attacks on the theories surrounding the ability of tobacco to cure diseases began early in the 17th century, with King James I publically denouncing the treatment. In 1811, English scientist Benjamin Brodie demonstrated that nicotine, the principal active agent in tobacco smoke, is a cardiac poison that can stop the circulation of blood in animals. This ground breaking report directly led to a quick decline in the use of tobacco smoke enemas in the medical community. By the middle of the 19th century, only a small, select group of medical professional offered the treatment.

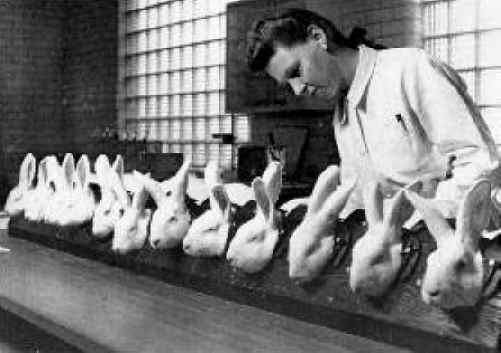

It is an advantage for a woman to understand that she is pregnant before having a child. It allows her to mentally prepare for the birth and avoid using drugs and alcohol. As you can imagine, world history is full of bizarre techniques that were used to test for human pregnancy. In ancient Greece and Egypt, watered bags of wheat and barley were used for this purpose. The female would urinate on the bags and if a certain type of grain spouted, it indicated that she was going to have a child. Hippocrates suggested that if a woman suspected she was pregnant, she should drink a solution of honey water at bedtime. This would result in abdominal cramps for a positive test. During medieval times, many scientists performed uroscopy, which is an ineffective way of examining a patient’s urine. In 1928, a major breakthrough in the development of pregnancy tests was made when two German gynecologists named Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek introduced an experiment with the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Before this time, hCG was thought to be produced by the pituitary gland, but in the 1930s, Georgeanna Jones discovered that hCG was produced by the placenta. This discovery was vital in the development of modern day pregnancy tests, which rely heavily on hCG as an early marker of pregnancy. In 1927, Zondek and Aschheim developed the rabbit test. The test consisted of injecting the woman’s urine into a female rabbit. The rabbit was then examined over the next couple days. If the rabbit’s ovaries responded to the female’s urine, then it was determined that hCG was present and the woman was pregnant. The test was a successful innovation and it accurately detected pregnancy. The rabbit test was widely used from the 1930s to 1950s. All rabbits that were used in the program had to be surgically operated on and were killed. It was possible to perform the procedure without killing the rabbits, but it was deemed not worth the trouble and expense. Today, modern science has evolved away from using live animals in pregnancy tests, but the rabbit test was considered a stepping stone during the middle of the 20th century.

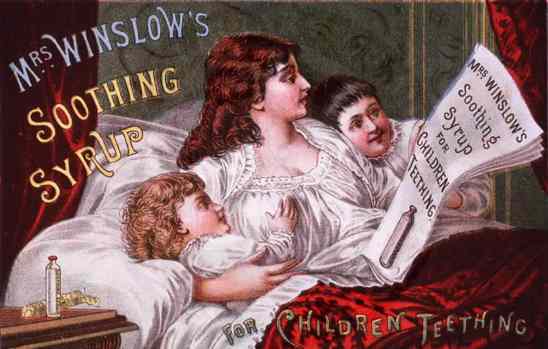

During the 19th and 20th centuries, as the world’s population began to expand, many industries experimented with a wide range of medicines. During this time in history, the scientific community conducted many trials with new drugs. New substances were often discovered that had a direct impact on the human brain. In some cases, international companies took advantage of the loose market standards and released potentially hazardous products. A good example of this is Mrs Winslow’s soothing syrup, which was a medical formula compounded by Mrs. Charlotte N. Winslow, and first marketed in Bangor, Maine, USA, in 1849. The product was advertised as “likely to sooth any human or animal”, and it was specifically targeted at quieting restless infants and small children. The formula’s ingredients consisted of a large amount of morphine sulphate, powdered opium, sodium carbonate and aqua ammonia. Mrs Winslow’s soothing syrup was widely used during the 19th century to calm wild children and help babies sleep. This cocktail of drugs worked immediately and slowed the children’s heart rate down by giving them harmful depressants. The syrup had an enormous marketing campaign in the UK and the US, showing up in newspapers, recipe books, calendars and on trade cards. During the early 20th century the product began to gain a reputation for killing small babies. In 1911, the American Medical Association incriminated Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup in a publication named Nostrums and Quackery, in a section titled Baby Killers. Mrs Winslow’s soothing syrup was not withdrawn from shelves in the UK until 1930. In 1897, chemists at the Bayer pharmaceutical company in Elberfeld, Germany, began experimenting with diacetylmorphine, or heroin. From 1898 through 1910, the Bayer Company sold diacetylmorphine to the public. The substance was marketed under the trademark name Heroin and was put on supermarket shelves as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough suppressant. In fact, the Bayer Heroin product was two times more potent than morphine itself and caused countless people to become addicted. The public response was immediately evident, but the company continued to sell Heroin for over ten years. The era has since become a historic blunder for the Bayer Company, and world organizations in charge of keeping people safe from these harmful chemicals.

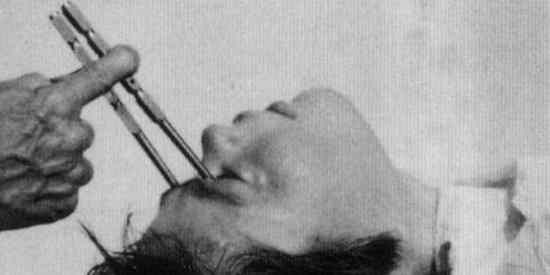

The first half of the 20th century will forever be known for a series of radical and invasive physical therapies developed in Europe and North America. Since the beginning of time, world cultures have treated mentally and physically challenged individuals in different ways. During the early 1900s, the medical community began developing some bizarre treatments. Some examples include barbiturate induced deep sleep therapy, which was invented in 1920. Deep sleep therapy was a psychiatric treatment based on the use of drugs to render patients unconscious for a period of days or weeks. Needless to say, in some cases the subjects simply did not wake up from their comas. Deep sleep therapy was notoriously practiced by Harry Bailey between 1962 and 1979, in Sydney, at the Chelmsford Private Hospital. Twenty-six patients died at Chelmsford Private Hospital during the 1960s and 1970s. Eventually, Harry Bailey was linked to the deaths of 85 patients. In 1933 and 1934, doctors began to use the drugs insulin and cardiazol for induced shock therapy. In 1935, Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz introduced a procedure called the leucotomy (lobotomy). The lobotomy consisted of cutting the connections to and from the prefrontal cortex, the anterior part of the frontal lobes of the brain. The procedure involved drilling holes into the patient’s head and destroying tissues surrounding the frontal lobe. Moniz conducted scientific trials and reported significant behavioral changes in patients suffering from depression, schizophrenia, panic disorders and mania. This may have something to do with the fact that the patient was now suffering from a mental illness and brain damage. Despite general recognition of the frequent and serious side effects, the lobotomy expanded and became a mainstream procedure all over the world. In 1949, António Egas Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine. During the 1940s and 50s, most lobotomy procedures were performed in the United States, where approximately 40,000 people were lobotomized. In Great Britain, 17,000 lobotomies were performed, and in the three Nordic countries of Finland, Norway and Sweden, approximately 9,300 lobotomies were undertaken. Today, the lobotomy is extremely rare and illegal in some areas of the world.

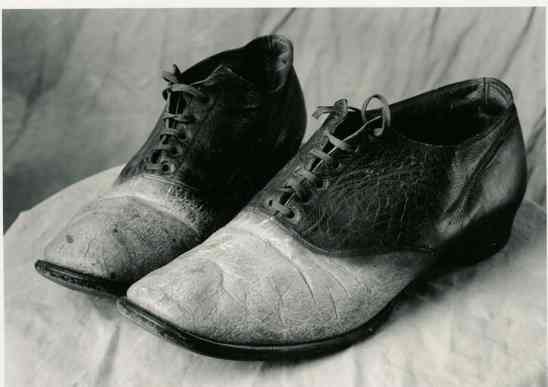

Anthropodermic bibliopegy is the practice of binding books in human skin. Surviving examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy include 19th century anatomy text books bound with the skin of dissected cadavers, estate wills covered with the skin of the deceased, and copies of judicial papers bound in the skin of murderers convicted in those proceedings. In America, the libraries of many Ivy League universities include one or more samples of anthropodermic bibliopegy. Towards the end of the 1800s, many outlaws emerged in the American West. One of these criminals was named Big Nose George Parrott. In 1878, Parrott and his gang murdered two law enforcement officers in the US state of Wyoming. The killings occurred as the men tried to escape a bungled train robbery near the Medicine Bow River. In 1880, Parrott’s gang was eventually captured by police in Montana. The men were apprehended after getting drunk and boasting of the killings. Big Nose George was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1881, following a trial, but he attempted to escape while being held at a Rawlins, Wyoming jail. When news of the attempted escape reached the people of Rawlins, a 200-strong lynch mob snatched George from the prison at gunpoint and strung him up from a telegraph pole. Doctors Thomas Maghee and John Eugene Osborne took possession of Parrott’s body after his death, in order to study the outlaw’s brain for signs of criminality. During these procedures, the top of Parrott’s skull was crudely sawn off and the cap was presented to a 15-year-old girl named Lilian Heath. Heath would go on to become the first female doctor in Wyoming, and is noted to have used Parrott’s skull as an ash tray, pen holder and doorstop. Skin from George’s thighs, chest and face was removed. The skin, including the dead man’s nipples, was sent to a tannery in Denver, where it was made into a pair of shoes and a medical bag. The shoes were kept by John Eugene Osborne, who wore them at his inaugural ball after being elected as the first Democratic Governor of the State of Wyoming. Parrott’s dismembered body was stored in a whiskey barrel filled with a salt solution for about a year, while the experiments continued, until he was buried in the yard behind Maghee’s office. Today the shoes created from the skin of Big Nose George are on permanent display at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, Wyoming, together with the bottom part of the outlaw’s skull and George’s earless death mask.

Scientific racism is the act of using scientific findings to investigate the differences between the human races. In history, this type of research was conducted in order to suppress individuals. It was most common during the New Imperialism period (1880-1914). During this time in history, some scientists tried to develop theories in order to justify white European imperialism. Since the end of the Second World War and the occurrence of the Holocaust, scientific racism has been formally denounced, especially in The Race Question (July 18, 1950). Beginning in the late 20th century, scientific racism has been criticized as obsolete, and as historically used to support racist world views. One example of scientific racism is a theory named drapetomania. Drapetomania was a supposed mental illness described by American physician Samuel A. Cartwright in 1851 that caused black slaves to flee captivity. Cartwright described the disorder as unknown to the medical authorities, although its diagnostic symptom, the fleeing of black slaves, was well known to planters and overseers. Cartwright delivered his findings in a paper before the Medical Association of Louisiana. The report was widely reprinted in the American colonies. He stated that the disorder was a consequence of masters who “made themselves too familiar with slaves, treating them as equals.” Quoting the document, “If any one or more of them, at any time, are inclined to raise their heads to a level with their master, humanity requires that they (slaves) should be punished until they fall into the submissive state. They have only to be kept in that state, and treated like children to prevent and cure them from running away.” In addition to identifying drapetomania, Cartwright prescribed a remedy. In the case of slaves “sulky and dissatisfied without cause,” Cartwright suggested “whipping the devil out of them” as a preventative measure.

The divine right of kings was a political and religious doctrine that asserted that a monarch has ultimate authority over man, deriving its right to rule directly from the will of God. The law ensured that medieval kings were not responsible for the will of the people, but rather working under God’s power. The doctrine implies that any attempt to depose the king, or to restrict his powers, runs contrary to the will of God and may constitute heresy. The theory came to the forefront in England under the reign of James VI of Scotland (1567–1625), James I of England (1603–1625), and also Louis XIV of France (1643–1715). The divine right of kings was slowed in England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689. The American and French revolutions of the late 18th century further weakened the theory’s appeal, and by the early 20th century, it had been virtually abandoned all over the world. The idea of the divine right of kings implicitly stated that no one but the king was worthy of punishing his own blood. This law created a problem for tutors in ancient times because the king was often times not available to raise his son. Royal educators found it extremely difficult to enforce rules and learning. For this reason, whipping boys were assigned to every young prince. When the prince would misbehave in class or cause problems for the tutors, the child’s whipping boy would be physically punished in front of the prince. Whipping boys were generally of high birth, and were educated with the prince since they were a young child. For this reason, the future ruler and whipping boy often grew up together and in some cases formed an emotional bond. This occurred because the prince did not have any other playmates or schoolmates to bond with. The strong connection that developed between a prince and his whipping boy dramatically increased the effectiveness of using this technique as punishment for the royalty. However, as history has often taught us, some rulers have no sympathy for others who are perceived to be a lower class. In these cases, the royal whipping boys were tortured at the expense of the prince. The principle of the divine right of kings molded young ruler’s minds into the perception that they were untouchable. The life of a whipping boy was usually one of sorrow and pain. These children are noted for being an example of one of the first fall guys.

The Sengoku period of Japan was an era characterized by social upheaval, political intrigue and near constant military conflict. Dating far back into Japanese history, warriors have been known to take human trophies, specifically the heads of their enemies slain on the battlefield. Often time’s remuneration was paid to these soldiers by their feudal lords based on the severed heads. By 1585, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had become the liege lord of Japan. Hideyoshi is historically regarded as Japan’s second “great unifier.” From 1592-1598, the newly unified Japan waged war against Korea. The ultimate goal of the offensive was to conquer Korea, the Jurchens, Ming Dynasty China and India. During this time in history, the gathering of war trophies was still highly encouraged. However, because of the sheer number of Korean civilians and soldiers that were killed in the conflict, and the crowded conditions on the ships that transported troops, it was far easier to bring back ears and noses instead of whole heads. The dismembered facial features of Korean soldiers and civilians killed during the war were brought back to Japan in barrels of brine. It is impossible to be sure how many people were killed, but estimates have been as high as one million. Remarkably, the incredibly large amount of decapitated Korean noses and ears taken into Japan during this time in history is still highly visible. You see, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had massive structures constructed that contained the sliced ears and noses of the killed Korean soldiers and civilians taken during the war. The largest such monument is named Mimizuka and it enshrines the mutilated body parts of at least 38,000 Koreans. The shrine is located just to the west of Toyokuni Shrine, in Kyoto, Japan. The Mimizuka was dedicated on September 28, 1597. The exact reasons it was built are unknown. It was uncommon for a defeated enemy to be interred into a Buddhist shrine. The Mimizuka is not unique. Other nose and ear mounds dating from the same period are found elsewhere in Japan, such as the Okayama nose tombs. With the expansion of the Internet, some Japanese civilians have learned about the Mimizuka. However, for a long time, the Mimizuka was almost unknown to the Japanese public. The shrines are rarely mentioned in Japanese high school text books. However, most Koreans are well aware of its existence. In many areas of Korea, the Ear Mounds are seen as a symbol of cruelty, while other Korean’s feel the Mimizuka should stay in Japan as a reminder of past savagery. It is a controversial subject and even today the majority of people who visit at Mimizuka are Korean. This may have something to do with the fact that most Japanese tourist guidebooks do not mention Mimizuka or anything about its disturbing history.

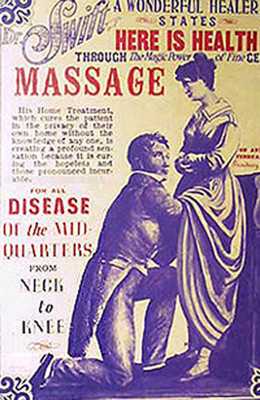

Female hysteria was a once-common medical diagnosis, found exclusively in women, which is today no longer recognized as a disorder. The diagnosis and treatment of female hysteria was routine for hundreds of years in Western Europe and America. The disorder was widely discussed in the medical literature of the Victorian era (1837-1901). In 1859, a physician was noted for claiming that a quarter of all women suffered from hysteria. One American doctor cataloged 75 pages of possible symptoms of the condition, and called the list incomplete. According to the document, almost any ailment could fit the diagnosis for female hysteria. Physicians thought that the stresses associated with modern life caused civilized women to be more susceptible to nervous disorders, and to develop faulty reproductive tracts. Women considered to be suffering from hysteria exhibited a wide array of symptoms, including faintness, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in abdomen, muscle spasm, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and “a tendency to cause trouble”. The history of this diagnosis is obviously controversial because of the wide range of bizarre symptoms and causes, but the case gets more shocking when you look at the treatment. During this time, female hysteria was widely associated with sexual dissatisfaction. For this reason, the patients would undergo weekly “pelvic massages.” During these sessions, a doctor would manually stimulate the female’s genitals, until the patient experienced repeated “hysterical paroxysm” (orgasms). It is interesting to note that this diagnosis was quite profitable for physicians, since the patients were at no risk of death, but needed constant care. Pelvic massages were used as a medical treatment on women into the 1900s. Around 1870, doctors around the world realized that a new electrical invention could help the vaginal massage technique. You see, in many cases physicians found it hard to reach hysterical paroxysm. I think you can imagine why this would be the case. In 1873, the first electromechanical vibrator was developed and used at an asylum in France for the treatment of female hysteria. For decades, these mechanical devices were only available to doctors for the use in pelvic massages. By the turn of the century, the spread of home electricity brought the vibrator to the consumer market. Over the course of the early 1900s, the number of diagnoses of female hysteria sharply declined, and today it is no longer a recognized illness.