Ian Fleming probably didn’t realize what a seed he was planting when he created James Bond. Almost immediately after his big screen debut, Bond had a whole generation of imitators following him on TV and film. There were suddenly spies everywhere—some surreal and campy, others sophisticated and witty, some hip and groovy. There was even a wedding of the spy with the western. By 1970, the anti-establishment sentiments of the hippies had fully taken hold in pop culture, and the spy craze was suddenly no more. Only James Bond was left, last as he was first, to carry on. PLEASE NOTE: This list excludes Bond—this is, of course, about the OTHER spy series of the day. Bond, naturally, is the biggest and best known. The point is, he wasn’t alone.

One of the iconic bits of Sixties spy shtick was the weekly-repeated, unforgettable speech of the unseen, unknown voice on the tape recorder: Good morning, Mr. Phelps. Your mission, should you decide to accept it… as though Phelps ever would have refused. The dirty secret of spies, of course, is that they aren’t allowed to refuse. If you refuse, John Drake (of “Danger Man,” etc.) could tell us, they kill you—or worse, they send you somewhere. And their “somewheres” are never pleasant; Villages and gulags of all sorts, and it doesn’t matter whose side you’re on—in the end they’re all the same place. To punctuate this truth, there was that ominous caveat spoken near the end of each of Mission: Impossible’s mission tapes: if you or any of your IM Force are caught or killed, the Secretary will disavow all knowledge of your actions. In other words, you’re on your own, pal, and nice knowin’ ya. And to further emphasize the idea that there would be no witnesses, no paper trail, no trace of a chain of command should Phelps and his team fail: this tape will self-destruct in five seconds. Perhaps Phelps could count on vanishing just as quickly if he decided sometime to say, “no, I’m not takin’ this one.” But of course he never did—Peter Graves was far too reliable, and, yes, wooden, for such dramatic disobedience. So every week he and the faces of his ever-changing group of IMF spies and professionals would take on another corrupt dictator or spirit another willing defector out of the hands of the commies. Cast changes were part and parcel of Mission: Impossible, and the faces changed more than the improbable and occasionally formulaic plots. The original “team leader,” Dan Briggs, (played by Steven Hill) left after the first season and was replaced by the aforementioned Graves. Then, later, master of disguise Rollin Hand and resident hottie Cinnamon Carter (played by Martin Landau and his wife of the time, Barbara Bain) left, to be replaced by Leonard Nimoy, in his first post-Spock role as “The Great Paris”, and Linda Day George, among a slew of others. Stolid strongman Peter Lupus remained throughout the show’s run, as did Greg Morris. But none of these characters, nor the actors who played them, made the cut of the successful films based on the series (starring the annoying and detestable master scientologist himself, Tom Cruise) though there was a brief TV revival in the Eighties. Interesting tidbit: Mission: Impossible was the “sister show” of the original Star Trek – the two series were filmed back to back and side by side at the same Desilu Studios by the same production team, though their creative teams were totally different. Star Trek, on its slim budget, would often “borrow” props from Mission: Impossible, paint them weird and garish colors, and pass them off as alien sculpture and whatnot for visual ambience.

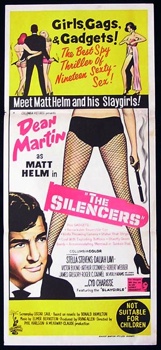

Introduced in a series of novels by Donald Hamilton, the Matt Helm character was originally a somewhat out-of-shape, aging spy, gnarled and grizzled, somewhat in keeping with the spies of old. When, however, Matt finally reached the silver screen, he had morphed into a parody James Bond, a slick lounge lizard with a bevy of spy babes around him, part comic Bond and partly a reflection of the persona of the man who played him in four films, Dean Martin. Martin’s Matt Helm was one of the chief inspirations for Mike Myers’ Austin Powers… amongst other similarities, the “secret identity” of each character was the same: fashion photographer.

The idiot as spy, as it were, Don Adams’ Maxwell Smart was the creation of the keen and deadpan wit of Mel Brooks and Buck Henry, late of the writing staff of That Was the Week that Was and future host (ten times over) of Saturday Night Live, and eternal straight man to John Belushi’s rotating Samurai character. Maxwell Smart labored for the ever-suffering Chief against the sinister machinations of KAOS, usually facing peril at the hands of Bernie Kopel (later to be granted a floating medical degree on The Love Boat) and his Silly Eastern European Accent. Max had at his disposal, of course, all the tools of the trade for fighting the pesky adversaries out for world domination: shoe-phone, cones of silence (their use, naturally, meant that you couldn’t hear what the other guy was saying, but what the hell), robots (Hymie, played by slick Dick Gautier, perennial game show celeb), and best of all, a beautiful female partner—one of the best of her league—the nameless but gorgeous Agent 99, played cutely and smartly by the cute and smart Barbara Feldon, object of this writer’s affections when he was but a tadpole. Yes, spies could be funny. Why not? The trappings of Sixties Spydom were so ludicrous as it was—not just in fiction, but in fact. Why not Maxwell Smart and his “sorry about that Chief,” or, “missed it by that much,” when our own CIA was trying to snuff Castro with poisoned mustache wax, or the British MI6 was being sold down the river by turncoat double agents named Kim? Now that’s funny.

Unless you’re just too young to know this—or don’t ever bother to watch TV Land—or you spent the bulk of your life living under a large block of sandstone—you know that the western was the most successful and most popular genre of TV series in the 50s and 60s, with its only serious contender being the cop drama. Well police shows are still with us, but the western is long gone, and not just from our TV screens but largely from our movie theaters as well. Oh, every so often there’s talk of a resurgence of the western in films, and there’s been quite a few good ones in the last twenty years. But it’s never really come back, and certainly not to television. Perhaps we’re too sophisticated and jaded and gritty urban, these days, for hicks on horses. But once upon a time the western was the big thing. And there were some great ones in the 60s – Bonanza being the best, arguably, along with Gunsmoke and The Big Valley, Bat Masterson, Have Gun Will Travel, The Rifleman… well, you get the idea. But the 60s were also the decade for Pure TV Escapism and Swinging Fun, the decade of Star Trek, Batman, Hullabaloo… of Lost in Space, Land of the Giants, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea… and it was also the decade of the subject of this list… the decade of Swingin’ Spies. So what would be more natural than combining the western with the spy? Thus, the heroes of Wild Wild West—agents of the United States Secret Service waging war on the 19th century frontier against such villains as the diminutive mad genius, Miguelito Loveless. Occasionally surreal (what else could it be?) with its bizarre villains and their bizarre schemes, the show’s strength was its buddy relationship between handsome tough guy Robert Conrad’s Jim West and Ross Martin’s urbane master of disguise Artemus Gordon. Remade as an unmemorable film in the 90s, starring Will Smith and Kevin Kline.

Derek Flint, suave genius as spy, was the first parody secret agent in film. James Coburn played him fairly straight (unlike Dean Martin’s campy Matt Helm or Don Adams’ bumbling Maxwell Smart) but still, Flint was thoroughly over the top: the ultra-cool spy who was a master of everything—martial arts, science, electronics, food, languages… and of course a master with the ladies. Flint even had a bevy of multi-national babes who lived with him (so it seemed) and catered to his every needs. Sexist? You bet. Absurd? Oh yeah. But what fun, and who could take any of it seriously? Flint’s superhuman expertise was such that he could identify the boulliabase from a specific French restaurant by taste alone, dance a perfect Swan Lake with a Russian agent, go into rigid, impossible yoga trances at will, and any number of other impossible things.

Ian Fleming helped create this series—one of the first spy shows on American television—and lent to the hero the name of one of his characters: Napoleon Solo, one of the mobsters in Fleming’s Goldfinger who dies at the hands of the eponymous character. Originally called simply Solo, the series incorporated a Russian partner, Illya Kuryakin (played by David McCallum) into the mix, to work alongside the lead character (Solo was played by the semi-redoubtable Robert Vaughn—I always thought of him as less an imposing figure than other secret agents). McCallum became a huge hit with teenage fans. UNCLE, of course, stood for United Network Command for Law Enforcement; acronyms were part and parcel of sixties spy-dom, which can be traced back to the line in Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest”: “FBI, CIA, OSI… we’re all part of the same alphabet soup” and as Bond had had supervillainous SPECTRE to look after, UNCLE had THRUSH — Technological Hierarchy for the Removal of Undesirables and the Subjugation of Humanity. Naturally all this silliness got out of hand after a while. There was Derek Flint’s ZOWIE, Get Smart’s CONTROL (and villainous KAOS) and after a while one wonders why, instead of Al Qaeda, we didn’t get something more inventive for our first world-wide terrorist organization. MAD ARAB anyone? At any rate, the show became popular enough to spawn a spin-off in The Girl From UNCLE, which was the ever-engaging Stefanie Powers playing another Ian Fleming-created character, April Dancer. Her partner in the series was Mark Slate, though she shared Solo’s boss, Mr. Waverly (the tarantula-swelling and Gregory-Peck-framing Leo G. Carroll, who delivered the aforementioned famous alphabet soup line in North by Northwest). Sadly not as successful as the parent series, Stefanie Powers was at least nicer to look at, in this writer’s humble opinion. And she swung with the best of the sixties swinging babes, let’s face it.

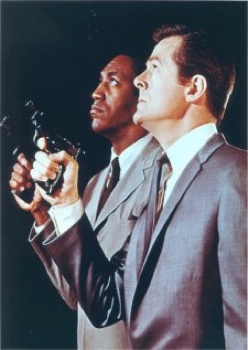

Another successful Sixties TV show later resurrected as a bad movie, I Spy, I always felt, had a certain edge to it. Oh, not a gritty, reality sort of edge… this was still the Sixties, when reality on television was not wanted, thank you. But there was something. Part of it had to do with Bill Cosby’s role as spy-in-training Alexander Scott—one of the first times in American television that a black man played in a starring role. He and fellow star Robert Culp (playing tennis pro-turned-tennis-bum Kelly Robinson, a fake ne’er-do-well who was actually a secret agent) had a buddy relationship which captured the affection of viewers, with their rapid-fire, hip banter and suave, smooth personalities. Also, the series was innovative in the way it went location-hunting, filming several episodes in Europe (Greece, Spain, etc.) and the far east. It never descended into camp territory, and like the British Danger Man, emphasized the somewhat harder-edged, tough side of the spy business.

Len Deighton’s Harry Palmer (played on the screen by Michael Caine in his first starring role) was meant to be a counterpoint to the ultra-sophisticated, upper-class James Bond. Palmer was working class, wore glasses, and lived in seedy surroundings. His sole “upper” quirks were that he was a gourmet cook and preferred to listen to classical music. Palmer’s insubordinate, vaguely criminal side was played up in the series—in fact, the story was that he had been an army sergeant arrested for some unexplained bit of illegality committed while he was stationed in Germany. Offered the chance to remain in the stockade or work for British Intelligence, Palmer wisely chose the latter—but he never found the compromise to be a comfortable one. Hating stiff-lipped bureaucracy and ever in fear that his stuffy, harsh boss (Colonel Ross) would send him back to prison—or worse—Palmer went through each mission with the omnipresent sense of having to look over his shoulder at all times. The Ipcress File is surely one of the best spy movies ever made (it has only one clunker of a moment: the line “that was the most delicious meal.”) and is particularly fun for not only Sydney Furie’s odd-camera-angle-direction and for John Barry’s influential and later highly-sampled soundtrack (bits of it, or riffs very similar to it, turn up in various trip-hop compositions from Portishead to Mono) but also for the remarkable insight into the tough and by no means glamorous day-to-day life of an agent for the government. Palmer is as close to a real human being as any secret agent gets—expressing his hope that, with a slight pay rise, he can buy that “new infrared grill,” or having to cope with the impending threat from an American agent (whose partner Palmer has accidentally killed) that he plans to “tail” Palmer until he’s satisfied that Palmer’s “clean, and if you’re not clean… I’m gonna kill you.” Not to mention the cold indifference of his superiors, who remark that, if the Americans do find anything suspicious about Palmer, they’ll take care of him, and save the Brits a lot of trouble. Not the happy life of women, fast cars, fun gadgets and martinis shaken-not-stirred that James Bond leads… for sure.

Lots of people have heard of the iconic and cult-fave series The Prisoner, but fewer people today know that Patrick McGoohan played the character (well, sort of) before, in a successful (and longer-lived) series called Danger Man. Of course, Americans knew the series by a different name: Secret Agent, and we knew very well its eponymous signature song by Johnny Rivers—a monster hit in 1966. (In the UK the signature tune was instrumental music very similar to that of the later series, The Prisoner). Danger Man had a long if bumpy run, going on the air in the UK originally in 1960 (thus predating the first James Bond film, Dr. No, by two years) and hanging on until 1968. McGoohan was cool and dispassionate agent John Drake, another “true-to-life” type almost as different from James Bond as Harry Palmer was, although Drake was clearly not working class. Drake was, however, a character increasingly displeased with his superiors’ sometimes unethical and cold-blooded tactics, and as the series wore on he was clearly becoming more insubordinate and more unhappy, as nearly every mission he was sent upon involved some kind of moral ambiguity or nasty compromise of principles that he was forced to endure. This, interestingly, set things up for McGoohan’s next series, the allegorical and Kafka-esque The Prisoner. McGoohan played “number six,” a British secret agent who had resigned because of some unknown disagreement with his superiors. As the opening credits and signature tune rolled and played for each episode, we were treated to a quick pastiche of what happened to the character: he resigns, angrily… he drives off, while, in a cavernous hall full of filing cabinets, his ID card is transported mechanically to a file, marked “RESIGNED.” He returns home and begins to pack… followed by a sinister character in funeral attire. Too late, he realizes his apartment is filling with gas. He faints… and then awakens in a room similar to his own… but not the same. Looking out a window, he sees he’s no longer in London… but in some bizarre spa-like Village. Then follows the now-famous bit of dialogue everyone knows: Where am I?” “In the Village.” “What do you want?” “Information.” “Whose side are you on?” “That would be telling…. We want information. Information! INFORMATION!” “You won’t get it.” “By hook or by crook, we will.” “Who are you?” “I am Number Two.” “Who is Number One?” “You are Number Six.” “I am not a number — I am a free man!” Each episode then involves a new plot by a different Number Two to try to break the will of Number Six. And each episode he wins… sort of. He escapes only twice: in an episode where he ends up spirited back to the village by a treacherous pilot, and in the final, surreal episode where… well… we’re not sure what really happens. Except that it appears “number six” has really been Number One all along. All in all, the entire series was an allegory for the struggle of modern man to maintain his freedom and independence in a world increasingly massified and totalitarian. Number Six is the ultimate individual who never gives in. But is he John Drake, McGoohan’s previous incarnation from Danger Man? Well legally, no… McGoohan didn’t own the rights to the earlier character he’d played. But surely, in every other sense, he was. Drake was the same kind of obstinate rebel, and he’d seen too many decent people suffer unfair consequences due to his own actions—because he was forced to follow orders. As Danger Man wore on he became more and more bitter—and there’s little doubt that the man who resigns, at the start of each episode of The Prisoner, is the same John Drake who had to do terrible things in the name of his government. Whatever the finale of The Prisoner meant—it was definitely John Drake’s ultimate triumph. He drove off, alone—and free.

Saving the best for last, we have The Avengers, the longest-lived of the Sixties spy series (1961 – 1969, with a revival series in the mid 70s). In its heyday, from 1965 – 1969, it was one of the most influential and most popular shows on British and American television, and its imagery become iconic overnight: umbrellas with tape recorders built into them, and bowler hats lined with steel; natty fashions straight of Swinging London—tight leather bodysuits and other figure-hugging outfits; champagne and liquor running freely (there hadn’t been as much imbibing by a couple since The Thin Man series); sports cars, Bentleys, and antique automobiles; cybernauts, electric men, invisible men, diabolical geniuses and deadly nannies… sometimes surreal and science-fictional, and always teeming with clever banter and double entendres. The constant was John Steed (the ever-graceful and ever-gentlemanly Patrick Macnee): originally a shady character who worked somewhat in the background, he first appeared in the life of Dr. David Keel, a surgeon whose wife had been murdered by a drug ring. Steed appeared to work for some unnamed, unknown official agency, though this was by no means made clear until later in the series. He and Keel spent their time tracking down crooks and other evil-doers to bring about their downfall… hence “the avengers,” bringing vengeance to those who otherwise would not be punished for their crimes. After Keel, John Steed was paired with Cathy Gale, a judo expert and another in the long line of “talented amateurs” that Steed worked with. It was now clear that Steed was a secret agent of some kind, and he was becoming less of the shady anti-hero and more of the trim sophisticate. But the true innovation was Gale. Played by the desirable Honor Blackman—who would leave the series to play “Pussy Galore” in Goldfinger—Cathy Gale was a kind of woman not seen before on television—tough, smart, strong-willed… a Sixties Sarah Connor. She was Steed’s match in the wit-and-banter department, and the sexual tension between them fueled the show’s popularity. Gale’s exit from the series came just as it was sold to American television… and Steed was on his own again. And then came… Mrs. Peel. We know Nick and Nora (the Thin Man and wife), Mulder and Scully, David and Maddie (Moonlighting)… but for many, there are none better than Steed and Mrs. Peel. In a way she was Cathy Gale with the edges smoothed a bit, but she was more. Honor Blackman had a rough desirability; but Diana Rigg had a more intellectual sexuality. She played Emma Peel (the name chosen because the producers had penned a note saying that Cathy Gale’s replacement had to have “M. Appeal”—“man appeal”) as a devastatingly intelligent, quick-witted expert-of-all-trades who also just happened to know martial arts and was a deadly shot. Indeed, Mrs. Peel killed more people than Steed had ever done (in fact, he offed very few in the series run) and where his photograph was marked by Russian agents with a notation that said “Very Dangerous,” hers simply read on the back, “Most Dangerous of All – AVOID.” The series went downhill somewhat after Rigg left, and Steed’s younger partner Tara King came on. After all, following up on that kind of chemistry was frankly impossible. The shows were highlighted with inventive and amazing plots, smart dialogue, fun and interesting characters, wild and weird villains, and set in an imaginary Britain where it was always summer and always sunny, and was ever Swinging Carnaby Street. But what made it the most enjoyable were Steed and Mrs. Peel—like being able to hang with the smartest, quickest and most fun couple imaginable—AND get to watch them best the villainous criminal, megalomaniac or foreign agent of the week. From maniacal geniuses out for revenge, to repugnant blackmailers who mark their targets with cards that read “You Have Just Been Murdered,” to homicidal androids and escaped lunatics, killer “robot houses” and madmen powered by “broadcast energy,” Steed and Mrs. Peel handled them all with nonchalant panache and confident detachment. Mrs. Peel… we’re needed.

Simon Templar (hero of a series of books by Leslie Charteris) or “the Saint” was an ambiguous rake of a character, brought to life by such distinguished actors as George Sanders, Ian Ogilvy, and Vincent Price (along with a latter day Saint portrayed by Val Kilmer). His best-remembered incarnation, however, was played by a pre-James Bond Roger Moore. (And in fact it’s Moore’s stint as the Saint that helped land him the role of Bond when Sean Connery walked away from it). The Saint was never actually established as a spy or secret agent per se; rather he is something of a criminal (but of the Robin Hood variety… occasionally anyway) and sometimes an amateur detective… but often he worked as a sort of free-lance agent of various police/government agencies, qualifying him as a member of the exclusive club of swingin’ sixties spies. After all, the Saint (particularly when played by Moore) had the whole image down pat. Suave, sophisticated, rakish, intelligent… a hit with the chicks and able to hold his own against the villains. His skills and talents were beyond the average man, and even his anti-hero status is in keeping with the overall idea of the best sixties spies—a sort of cheeky, smart rebel who does what has to be done.

The removable motion alarm stops thieves and intruders Case shoots darts (4 included) to “stun” enemy spies Removable flashlight spots hidden spies Special spy scope lets you spy from far away Case has a secret compartment and gear storage for more spy gear