Ruins give insights into unusual cities and how leaders ruled. Meanwhile, art gives unexpected glimpses into daily life and creations so unusual that even the experts failed to credit the Maya. This remarkable society also left lessons and mysteries for future generations.

10 Drought Monuments

In 2018, archaeologists headed to central Belize to visit an ancient Mayan site. At Cara Blanca rests the remains of two structures, a platform near a deep pool and a sweatbath complex. Both were built around AD 800–900 when the region was choked by droughts. During these trying times, pilgrims visited both buildings to honor the rain god Chahk. At first, the team wanted to search for more artifacts at the poolside platform and assess looting damage at the sweatbath. Instead, they discovered new insights into the sacred site’s past. While digging at the pool, a new platform was unearthed. Not only was it completely unexpected but it dated from AD 600. This meant that the landscape was used for rituals centuries before archaeologists thought it was built and also during a time that was likely drought-free. The sweatbath also held a surprise. The damage turned out not to be the handiwork of looters but of the Maya themselves, who dismantled the monument before they abandoned the site for good.[1]

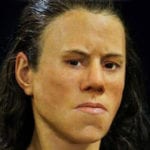

9 Face Of Pakal The Great

The Mayan king with the longest reign was K’inich Janaab’ Pakal. Also known as Pakal the Great, this beloved and important monarch ascended to the throne at age 12 in AD 615 and was still king when he died at 80. In 2018, archaeologists were excavating his palace in southern Mexico when they recovered a rare artifact. Pakal’s palace is already an engineering feat with many surprises. But when the team followed artificial waterways inside, they found a previously unknown indoor pool with seats. The same building also yielded a cache that included a life-size stucco mask. The mask was not the kind to be worn by a person. More likely, it was an architectural decoration. After comparing its facial features with images of King Pakal, a likeness emerged. The piece was crafted to show an elderly, wrinkled face. Since he ruled well into his old age, this also suggested that it was Pakal. If confirmed, it will be the first image depicting the king in his later years.[2]

8 Maya’s Environmental Footprint

For some reason, the idea spread that the Maya lived in total harmony with nature. They lacked greenhouse gases and plastic, but the culture did not leave nature intact. In 2018, researchers found evidence in the form of carbon—or the lack thereof. The Maya deforested on a massive scale. They needed firewood, farmland, and space for their temples. The culture folded around AD 900, and over the following 1,100 years, the tropical forests recovered. Today, most Mayan sites appear as ancient, untouched growth. However, several soil tests showed something disturbing—the land had not recovered. The trees may be there, but the earth can no longer store carbon like it used to—not even after a millennium without deforestation. In fact, the soil’s ability to retain carbon dropped dramatically. This is not the best news for climate change scientists who had hoped to use second-growth forests to capture excessive carbon.[3]

7 Clues About Snake Kings

In the Guatemalan jungle sleeps the ruins of La Corona, a rural Mayan city. The settlement was always believed to be isolated during the Classic period (AD 250–900). During this time, a dynasty of so-called snake kings ruled from Calakmul in Mexico. Little is known about how this kingdom ruled. In 2018, clues surfaced at La Corona. Aerial laser scanning found that thousands of people had lived at the supposedly isolated city. This already suggested that La Corona was not some forgotten backwater. Hieroglyphics told of local gods arriving again and how the rural city was under the jurisdiction of a kingdom. Archaeologists believe that La Corona was one of the settlements absorbed by the snake kings during their expansion. The “gods” were their chosen leaders who used local mythology to establish their right to rule. The number of engravings found at La Corona was also staggering considering its small area. Some were records and suggested that the settlement was a key post in the snake kings’ trade route funneling precious goods to the capital in Mexico. This kind of linked political system busts the traditional view that the Maya lived in separate city-states.[4]

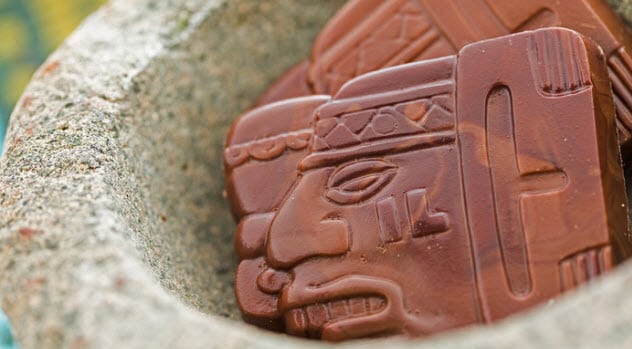

6 Chocolate Money

The Maya never used coins. Similar to many other ancient cultures, they likely bartered for necessities. In 2018, ancient art revealed something about their financial affairs—an edible currency. It is a well-known fact that the Maya were hot chocolate fans. In the past, scholars deduced from images that people consumed chocolate as a warm drink. The new art study suggested that not only did it make a good bartering piece but chocolate was also a form of tax. Pictures were chosen from the time when the Maya were at their peak, the Classic period (AD 250–900). They included murals, painted ceramics, and carvings. Market scenes showed that chocolate was used for bartering during the seventh century, sometimes in liquid form. By the eighth century, the prestigious food appeared to be used as money and tax in the shape of cacao beans.[5] Around 180 scenes showed tributes being delivered to leaders, including offers of tobacco and maize. The most frequent “tax” goods in art were identified as woven cloth and cacao beans.

5 Maya Blue

Human sacrifices and terrifying gods aside, the Maya were very artistic painters. They invented a rare color that was used in murals (and splashed on sacrificial victims). Today, it is known as Maya blue, and it took centuries for archaeologists to connect the shade and its creators. During 17th-century Europe, blue was a difficult pigment to obtain and only the masters were allowed to use it. At the time, it was produced—with great effort—from lapis lazuli stone in Afghanistan. Historians were surprised to discover that 17th-century painters from Spanish colonies in the New World used blue in abundance. This was strange. The pigment should have been scarcer in the New World than in Europe. Only during the 20th century did they realize that the limitless blue came from the painters’ knowledge about ancient Mayan dyes, which were procured from plants. Maya blue was more durable than its European counterpart, remaining vivid today in ruins as old as 1,600 years. This resilience was only solved in the 1960s when it was determined that the blue dye from the anil plant was mixed with attapulgite, a rare kind of clay.[6]

4 Submerged Mayan Underworld

In 2018, a diver investigated a small opening inside a submerged tunnel in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. As it turned out, the gap connected the Dos Ojos system and the Sac Actun cave system. This merger resulted in the world’s longest underwater cave. Experts descended on the tunnel, and incredibly, they identified 200 places that held archaeological remains. Among the things found in the 347-kilometer (216 mi) labyrinth were Mayan altars and incense burners. The latter showed images of Ek Chuah, their god of commerce. Such ritual items suggested that the cave was once part of the Mayan “underworld.” The culture believed that caves and water-filled sinkholes were doorways to the underworld and that such places spawned mankind. The preservation inside the underwater tunnel was excellent, and the sheer volume of discoveries was overwhelming. Hailed as the most important submerged region on Earth, the cave contains 15,000 years’ worth of pristine information. Apart from finding mostly Mayan artifacts, there were also fossils of extinct ice age cave bears, proto-elephants, giants sloths, and a skull that could belong to a new human species.[7]

3 Unusual City Growth

When cities grow, they tend to become denser. In other words, as the population increases, people live and work in closer proximity to each other. Researchers always thought that this encouraged the sharing of ideas and learning within a society. The tendency surfaced in most civilizations, even when they were completely separated by centuries and continents. The Maya did not follow this trend. When one of their cities grew, it expanded outward. Instead of living closer to neighbors, people engaged in what archaeologists now call “low-density urbanism”—avoiding density by moving the city’s outer borders. The Maya appeared to have liked their space, but where does that leave the close-proximity benefit of faster education? The Maya were masters of many fields, so it clearly did not impact their information sharing or learning. This unusual approach challenges the very definition of a city and the old notion that cities grow denser. Archaeologists are not even sure if Mayan society worked differently or whether this pattern is somehow an odd result of how ruins have been studied.[8]

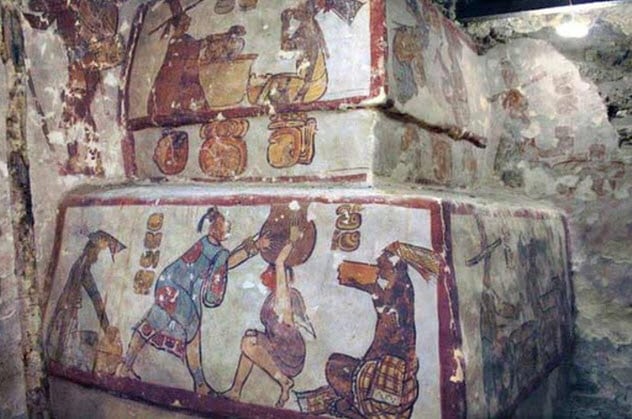

2 Glimpse Of Ordinary Maya

Lower classes made up the majority of the Mayan nation. Even so, murals and other forms of art focused almost exclusively on the elite classes. For this reason, the bulk of what daily life was like for the Maya is now lost. In 2009, researchers cleared a painted pyramid at Calakmul, Mexico. One wall had a mural, and to everyone’s shock, it showed normal Maya at work. This may sound like a tepid find, but it is the first discovery of its kind in the history of Mayan studies. The rare glimpse showed people preparing food like maize gruel, processing tobacco leaves, and drinking from pots. Each scene carried hieroglyphics to explain the person’s job or chore. Rarity was not the only prize. The hieroglyphics revealed for the first time the Mayan words for “maize” and “salt.” Interestingly, ancient builders renovated the structure and destroyed some layers and walls. But for some reason, they chose to carefully preserve the mural beneath a layer of clay. It is not clear why or even what the pyramid was for.[9]

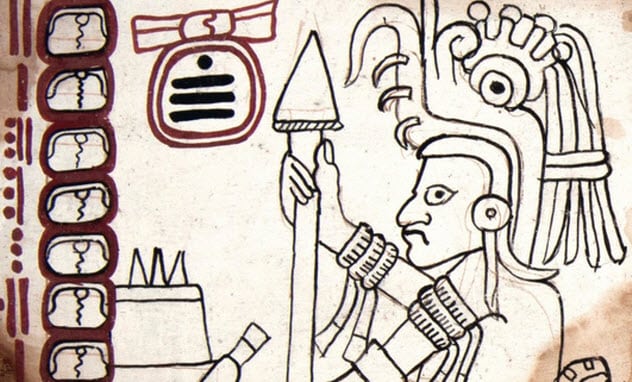

1 The Oldest Codex

In 1964, a Mayan document surfaced. Created on tree bark and containing images of Venus, the codex was deemed a fake by many. Critics said it looked unlike any other known Mayan codex and was too simplistic to be real. It changed hands several times until 1974, when an antiques collector donated it to the Mexican authorities to establish its authenticity. Years passed, and many continued to doubt the so-called Mayan Codex. Although it was old, it was a looted artifact, which erased clues about where it had been found. Without such valuable information, its “ugly” simple drawings and unique style (that did not look Mayan) continued to promote the notion of a hoax. In 2018, the bomb dropped. Tests revealed that the long-shunned document was not only authentic but also the oldest pre-Hispanic manuscript in the Americas. It was drawn between AD 1021–1154 and looked different because of the time’s poverty. People created art with whatever materials were available. This is the first-known document from that era, and it joins a handful of texts that survived burning by the Spanish during the 16th century.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages