From fierce Vikings who did not use their swords to clumsy-looking paddles designed to crush skulls, unexpected uses are coming to light. Researchers also look to weapons to clarify old murder cases, unknown cultures, and the ways in which nobility quietly killed each other off.

10 Saga’s Sword

In 2018, an eight-year-old girl went for a swim near her family’s holiday home in Sweden. At one point, Saga Vanecek stepped on something. The object she pulled out of Vidostern Lake reminded her of a sword. When she told her father she had found something with a handle, he thought it was just a weird branch. However, when he showed the crusty thing to a friend, the truth dawned. Saga had been right all along. Researchers at the local museum in Jonkoping County confirmed her diagnosis—it was a sword.[1] Expert analysis proved that the rare relic was a 1,500-year-old pre-Viking weapon. In addition, the blade was well-preserved. Sword fans can thank the region’s drought for this discovery. The dry spell lowered the lake’s water, and this was likely the reason why Saga found the sword. Its presence suggested that more ancient trinkets might be lurking in Vidostern. Indeed, when the museum staff investigated, they found a third-century brooch.

9 The Buzau Sword

In 2018, a worker did his shift at a gravel pit in Buzau, Romania. That day, his job placed him at the site’s conveyor belt. To his surprise, he found a sword among the debris. The man immediately handed the artifact over to the right authorities, which was lucky because this was no ordinary sword. It was over 3,000 years old and forged sometime during the Late Bronze Age. Interestingly, it was made in a mold that created decorations on the surface. The blade, measuring 47.5 centimeters (19 in) long and 4 centimeters (1.6 in) wide, was in good condition. Sadly, the handle was gone. Made of some kind of organic material, it had decomposed and disappeared over time. The sword was among the best finds to recently come out of Buzau and could be the tip of the iceberg. There is a chance that its owner, most likely a nobleman, might be buried near the gravel pit or even inside it.[2]

8 Africa’s Bone Age

The Stone Age in Africa is notable for one thing. Besides stone tools, people were adept at making bone implements. In 2012, archaeologists found a knifelike artifact near Morocco’s coast. The quality suggested that bone craft had hit a remarkable level around 90,000 years ago. Prior to this discovery, bone-cutting tools were used for simple and general tasks. However, this one appeared to be a specialized knife. Analysis indicated that it was used to cut something soft, most likely leather. The hands that made it belonged to the Aterian culture, a society dating as far back as 145,000 years ago. With exceptional skill, the knife maker took the rib of a cow-sized animal and split it lengthwise. One half was worked into the 13-centimeter-long (5 in) artifact. This find is not just about being good at making things from bones. It also challenged the idea that advanced toolmaking (to support survival) did not happen until much later.[3]

7 North America’s Oldest Weapons

When it comes to ancient spear points in North America, the Clovis variety was the oldest. This lost culture invented trademark stone tools from 13,000 to 12,700 years ago. In 2018, the dream of finding spear points older than Clovis came true. Archaeologists at a Texas site that had been under investigation for 12 years came across a dirt layer containing Clovis and Folsom points. (Folsom is a younger culture.) Beneath this layer were the long-awaited pre-Clovis spears. Made of chert and measuring 8–10 centimeters (3–4 in), the points were jumbled together with other tools. The age of the surrounding sediment dated the cache to a record-breaking 15,500 years.[4] This introduced a new hunter society as America’s first arrivals, an accolade that had always been given to the Clovis culture. In addition, the weapons were positively identified as game hunting equipment, the first to be discovered from any pre-Clovis site. Previous finds were usually just stone tools.

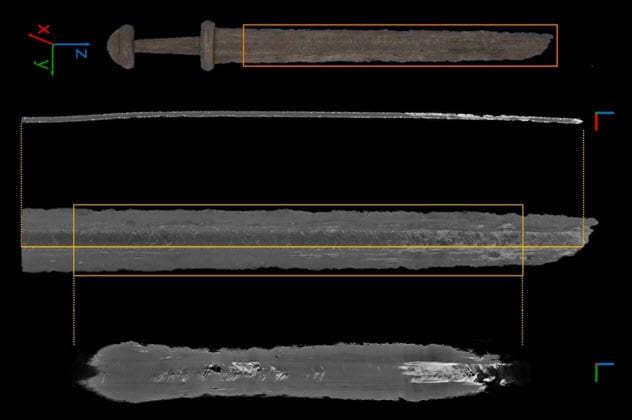

6 Brittle Viking Swords

To date, around 2,000 swords from the battle-loving Vikings have been recovered. However, not all were used for fighting. In 2017, a study looked at three swords from Denmark dating from the ninth and 10th centuries. In a world first, the weapons were analyzed with neutron scans. This technology could peek deeper than X-rays into the metal. The process took digital slices of each sword. The images revealed that the blades were produced using a technique called pattern-welding. Iron and steel strips were welded together, folded, and tweaked in different manners. This produced patterns on the sword’s surface. It also made these particular weapons unsuitable for fighting. Normal fighting swords had steel edges with impact-absorbing iron cores.[5] The three Danish swords did not have this composition. In addition, the metal strips were treated to high temperatures, a habit that could have caused oxides to appear on their surfaces. This weakened the weapons and probably caused them to rust more quickly. The swords were probably elite symbols and not actual weapons.

5 Unknown Warrior Class

In 2018, archaeologists worked at an old site north of New Delhi, India. During the three-month excavation, they found several things suggesting the existence of an unknown warrior class. At the village of Sinauli, the team uncovered eight tomb sites with some chariot remains. The three horse-drawn vehicles came from chambers built around 2000 BC to 1800 BC. Apart from suspecting that these were royal burials, the presence of weaponry supported the notion of warriors. Archaeologists found shields, daggers, and swords strong enough to be used in battle.[6] Four-thousand-year-old chariots and an elite warrior class described by the team as “technologically on par with other ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia and Greece” were fine enough. However, the coffins were also a unique find on the continent. The copper decorations that adorned the caskets had never been seen before. The culture to which the artifacts belonged remains unknown. They were found near graves belonging to the mysterious Indus Valley Civilization, but researchers are certain that the two were separate cultures.

4 A Poison Ring

In the archaeological record, assassin accessories do not show up often. In 2018, excavations in Bulgaria found a ring that probably killed a few people. It was discovered at the medieval ruins of Cape Kailakra, home to the 14th-century elite of the Dobrudja region. Other jewelry was found at Kailakra, but those pieces were normal gold and pearl decorations. The bronze ring was 600 years old, beautifully made, and probably imported from Spain or Italy. Suspiciously, the interior was hollow and came with a side cavity. The latter was an inconspicuous, easy way to tip poison out of the ring. Made for the little finger of a man’s hand, it showed that the assassin was right-handed. The cavity sat on the right, and a quick tilt would have poured death into his victim’s drink.[7] Archaeologists suspect that the ring could be linked to an old medieval mystery. In the 14th century, a man called Dobrotitsa ruled the region. History tells of many unexplained deaths around him, especially aristocrats and nobles. These deaths were probably political murders.

3 Norway’s Weapon Graves

In recent times, researchers have investigated the weapon graves of Norway. The tombs contained arms carried by the deceased during their lives. Researchers found a remarkable story. Although Norway was far away from Rome, there was a connection, especially with weaponry. Graves dating to the time when the Roman Empire flourished contained weapons reminiscent of Roman legionnaires (swords, lances, shields, and javelins). However, when the empire collapsed around AD 500, the axe suddenly became a popular burial weapon. This was odd. Ancient Norwegians fought like the Romans—on battlefields with rules where axes had no place. Researchers suspect that this weapon became the favorite after a more brutal turn of events. After the empire’s demise, the consequences hit Norway badly. Major alliances crumbled, and distant enemies were no longer the main target. The country descended into chaos, warlords popped up like mushrooms, and everybody fought each other. The axe was perfect for domestic guerrilla warfare that probably saw raids, violent clashes, and attacks on leaders and their homes.[8]

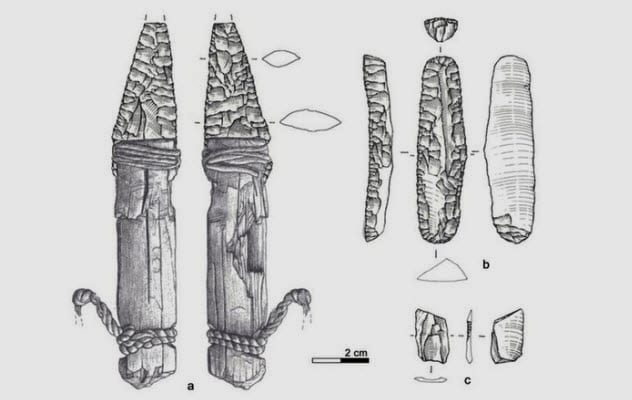

2 Otzi Surprised By Attacker

Years after his discovery in the Italian Alps, Otzi now ranks as one of the best-studied mummies in the world. Everything from his health to his genes has been checked. For some reason, his tool kit did not receive the same thorough investigation. In 2018, the combined collection of tools and weapons were scanned. The 5,300-year-old cache delivered interesting clues to the ongoing debate about what had happened to this man. He was undoubtedly murdered by a well-placed arrow. What remained unclear was whether he expected the enemy. Researchers analyzed a dagger, borer, end scraper, flake, antler retoucher, and pair of arrowheads. Apart from showing that the 45-year-old’s culture traded widely for the chert from which most of his weapons were made, cut marks revealed something interesting. In the days before his death, Otzi sharpened some of his tools. The end scraper and borer showed fresh modifications, but none of his weapons did. Otzi likely thought he was safe and prepared the two tools for a chore. Who killed this man so far up in the lonely Alps remains a mystery.[9]

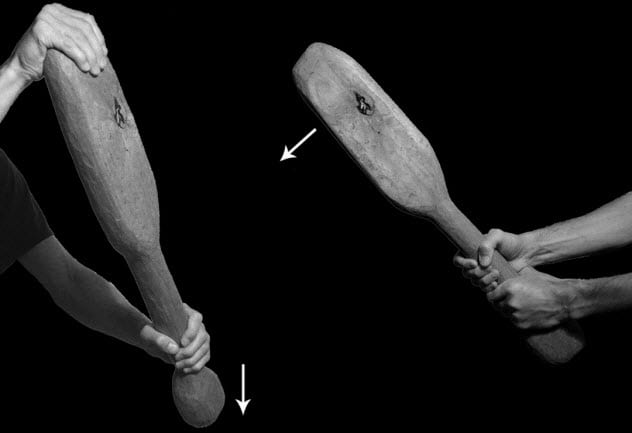

1 Thames Beater

The Stone Age was violent. Many skulls showed the preferred way of killing—bashing somebody in the head. In 2017, researchers tried to identify the weapon of choice. The study focused on victims from Neolithic Europe because violence was abundant in the region. The era had archers, but the idea was to find something used only on people. It should not double as a hunting tool. The Thames beater fit this profile. A 5,500-year-old wooden artifact resembling a cricket bat was pulled from the River Thames. Researchers whipped up a replica and artificial human skulls, complete with skin, bone, and brains. The beater was handed to a healthy 30-year-old man, who was asked to attack the heads as if his life depended on it. The results delighted the team. They never asked the volunteer to try to replicate the fractures, just to start hitting heads. Despite this, the wounds closely matched Neolithic injuries. One artificial skull even resembled a broken skull found at a 5200 BC massacre. The clumsy-looking Thames paddle turned out to be deadly. It was likely designed to serve exclusively as a human-killing device.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages