There are also the inevitable burials and bodies, but even these reveal intriguing architecture, facts, and unique artifacts. Some elaborate graves are not even for the living. The pyramids also continue to add new discoveries, even the missing ones.

10 Cemetery Of Thoth

A fruitful find insured that 2018 might become another bumper year for Egyptologists. Outside the city of Minya in the Nile Valley, a large necropolis was unearthed. The country is known for its dead and their cemeteries. But the Minya tombs did not contain civilians or pharaohs. Instead, they yielded priestly families. In life, the priests served the god Thoth, whose realms include wisdom and the Moon. One of the tombs belonged to a high priest and harbored over 1,000 statues. Forty family members shared his space, each in their own sarcophagus. The priest’s internal organs were located in four funerary vessels, known as canopic jars. Hieroglyphics adorn the jars and some of the family’s coffins. The priest himself was dressed with beads and bronze sheeting. The region is also known for mass burials of mummified birds, animals, and catacombs from the Pharaonic Late Period and the Ptolemaic dynasty. This latest discovery will take an estimated five years to fully catalog and study.[1]

9 Inside Luxor’s Private Tombs

The city of Luxor is famous for its ancient architecture and tombs. Among the latter are private tombs catching a view from the west bank of the Nile. Two were breached for the first time in late 2017. Found to be 3,500 years old, they probably held high officials as the cemetery was designed for elite Egyptians. Even so, the pair of tombs was small. Interesting building touches made up for a lack of grand space. One grave had a courtyard with mud and stone walls as well as a tunnel connected to four additional chambers. Wall decorations indicated that the person had been buried during the 18th dynasty, either during the rule of King Amenhotep II or King Thutmose IV. The second tomb’s designers felt the need to add five entrances, with each leading to the same rectangular room. The grave also contained two burial shafts and, unlike the first tomb, was packed with artifacts. These included masks, a bandaged mummy, ceramics, and 450 statues. The name of King Thutmose I on the ceiling relegated the burial to the early 18th dynasty.[2]

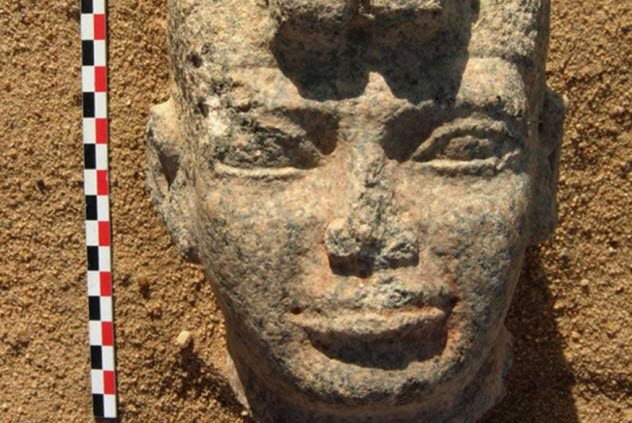

8 Face Of Aspelta

The kings of Kush once ruled ancient Egypt. By the time a ruler named Aspelta (r. 593–568 BC) came into power, they only governed their own kingdom. Even so, they kept referring to themselves as the kings of Egypt. Recently, excavations continued at Dangeil, an archaeological site in Sudan. Inside a temple of the Egyptian god Amun, researchers found sought-after fragments. They were among the missing parts of a statue discovered on location years ago. Pieced together, they revealed the face of Aspelta.[3] The 2,600-year-old statue was identified from one of the new pieces. Inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs, Aspelta was lauded as the “king of Upper and Lower Egypt” and the beloved of the Sun god Re. The statue, which appears to be life-size, was carved around six centuries after the temple was built next to the Nile. Interestingly, centuries after the building was abandoned, an elite group buried their members among the ruins. Nobody knows who these people were.

7 Sons Of Khnum-Aa

In 1907, two mummies started decades of frustration for researchers who love neat family links. Found 400 kilometers (250 mi) south of Cairo, the pair rested side by side for 4,000 years. Named Khnum-Nakht and Nakht-Ankh, they were probably nobility, judging by their rich tombs. Each coffin also bore the female name “Khnum-Aa.” She was described as the mother of both men, who were born about 20 years apart. However, scientists could not prove that she was their mother or that the men were brothers. There was no reference to their father except that he was a local ruler. After comparing the men’s physical traits, including skull shape and skin tone, researchers concluded that they were not related.[4] In 2018, DNA testing solved the mystery. Genetic material extracted from molars showed that the men shared a mother. However, they had different fathers. The half brothers represent a rare instance where an ancient claim of maternity can be double-checked with the individuals involved.

6 The Ankhnespepy Pyramidion

Queen Ankhnespepy II ruled Egypt until her son was old enough to be the pharaoh. Most of her funerary buildings have been found, including Ankhnespepy’s tomb and pyramid. She was influential and probably the first queen to have pyramid texts carved into her monuments. But now archaeologists are hunting her satellite pyramids. Late in 2017, an obelisk belonging to the queen was found near the Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo. Made of red granite, the obelisk was likely a part of her funerary temple, which would have had two obelisks—the trademark of sixth-dynasty queens. Just a week after the artifact’s discovery, a pyramidion (the tip of a pyramid) was unearthed nearby. This one was around 4,000 years old. It measured 1.3 meters (4.3 ft) high with a base that was 1.1 meters (3.6 ft) long. Considering its proximity to the obelisk and her husband’s pyramid, the granite piece could be the first physical recovery of a lost satellite. During its heyday, the pyramidion was probably sheathed in copper or gold to reflect the Sun.[5]

5 Hathor’s Musician

Around 3,200 years ago, an Egyptian woman died far from home. She was in her twenties and pregnant. Her discovery at a copper mine in Israel changed what archaeologists thought they knew about the place. At the time, Egypt controlled the region but the copper mines were located in an inhospitable place called Timna. It was arid and hardly encouraged settlers. But every winter, Egyptians visited the mines to extract metal. Until the skeleton was found in 2017, it was thought that women never made this journey. The Egyptian woman was important, too. Only people with status received proper burials at Timna. Experts believe that the woman was probably a temple musician or singer. Indeed, her grave was found close to a temple dedicated to Hathor. Among other realms, Hathor was the Egyptian goddess of mining, women, and music. The rare discovery is as tragic as it is history-changing. The young mother’s torso, arms, and head are all missing, likely the result of looting. But why she died so young remains a mystery that will probably never be solved.[6]

4 Statue’s Death And Rebirth

Ptah was the god of craftsmen and sculptors. In fact, these very artists created a statue of Ptah to be worshiped in a temple at Karnak. For years, the large limestone god enjoyed being fed, washed, and scented. In 2014, a pit was discovered next to the temple. Inside was the statue of Ptah in the company of a carved cat, sphinx, and baboon. Other god statues included Osiris and Mut. They were not discarded but viewed by the ancient Egyptians as “dead.” As such, Ptah’s statue received a proper burial. Its “life” ended about 2,000 years ago after it became too damaged to be of any use. Researchers feel that there was a purpose to the arrangement of Ptah’s grave. The inclusion of a sphinx was for protection, and an abundance of Osiris effigies (god of rebirth) could mean that the priests prepared the pit for the Ptah statue’s rebirth.[7]

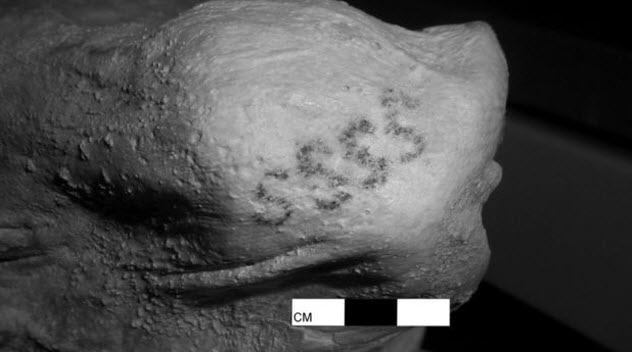

3 The Oldest Figurative Tattoos

Two shallow graves yielded the bodies of a man and a woman. The pair was found over a century ago in Gebelein, south of Luxor. The simple burials and lack of professional mummification showed that they were not important individuals. But their contribution to Egypt and the history of body art is enormous. For years, the dark coloring on the mummies’ arms was disregarded. There were more dramatic marks, such as the fatal stab wound to the man’s back. He was between 18 and 21 years old. Then in 2018, an infrared scan revealed the smudges were tattoos. A bull and Barbary sheep were identified on the man’s skin. S-shaped designs decorated the woman’s shoulder and upper arm and may have symbolized status, courage, and magic. At 5,000 years old, they push back the earliest age of tattoos in Africa by a cool millennium and globally represent the oldest body art involving illustrations. The images also corrected an assumption. Previously, it was believed that only women from ancient Egypt wore tattoos. But clearly, both genders enjoyed the habit.[8]

2 King Tut’s Camping Bed

When Howard Carter cataloged Tutankhamen’s grave goods in 1922, the bounty included several beds. One was a unique fold-up cot never seen before or since. Recently, the artifact underwent its first scientific analysis. It revealed a remarkably sophisticated design that was both practical and good-looking. Two-fold beds appeared to have been in existence before Tutankhamen, who died around 1323 BC. But the boy king’s bed was a groundbreaking three-folder that contracted into a tight Z. The piece of furniture bore the scars of attempts to perfect the folding mechanism. This supports the idea that the creators had no other three-folders to copy. The camping bed was invented for Tutankhamen.[9] Although the ancient artisans lacked previous experience with this kind of mechanism, their craftsmanship came through in the end. They devised a brilliant interplay between two different types of hinges, the ornate legs, frame, and linen matting. The bed was also more portable and comfortable than the double-folding versions. Researchers believe that Tutankhamen’s frailty prevented long journeys or hunts but that he was still passionate enough about them to have ordered the camping bed.

1 The Water Canals Of Giza

Although the Great Pyramid of Giza was built in 2600 BC, its construction remains a mystery. Researchers now believe that they have solved one step of the process. About 170,000 tons of limestone made the journey from Aswan, 805 kilometers (500 mi) to the south. Every day, 800 tons arrived to fatten up the Great Pyramid to a height of 147 meters (481 ft). Recently, the only firsthand account from one of the people involved was found. A papyrus scroll written by an overseer named Merer describes thousands of workers using wooden boats to transfer blocks along the Nile. Merer mentioned that, near the end, canals delivered the material to a port located a few paces away from the pyramid’s base. Physical evidence for Merer’s claims appeared when archaeologists found a waterway under the monument. They also identified a structure that was likely the main delivery basin for the 2.3 million blocks. The discovery added a new understanding of the complex infrastructure that evolved to build what remained the world’s tallest structure until the Middle Ages.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages