Appears in: Mary Jane #1-4, Mary Jane: Homecoming #1-4, Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane #1-20. Collected in: Mary Jane Vols 1-2, Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane Vols 1-4. The Mary Jane comics are one of Marvel’s many attempts to appeal to the preteen/teen girl demographic. It’s one of the few times that the comic book industry as a whole has tried and succeeded in creating an entertaining comic targeting young girls that wasn’t horribly sexist. The comic itself takes place in an alternate version of the Marvel universe where Mary Jane Watson and Gwen Stacy went to high school with Norman Osborne, Peter Parker, Flash Thompson, and Liz Allen. Despite occurring within a superhero infested universe, the book has very little superhero fare. Spiderman makes few appearances and is presented largely as an unrealistic celebrity crush of Mary Jane’s until very late into the comic’s run. The comic is largely centered around the typical teenage problems experienced by Mary Jane and her friends, particularly problems involving teenage dating and crushes. Thankfully Mary Jane completely shies away from more complex social issues facing teens like teenage sex and drug abuse, subjects that works of this nature seem drawn to and typically tackle in simplistic, unrealistic and condescending ways. At a glance the book does seem to lack any real depth, but if you give it a chance it does actually have a lot to say, particularly concerning teenage romance. And even if you’re not a teenaged girl, the book’s still a fun read. McKeever has written some of the most amazing and delightful dialogue to ever appear in a comic book. The characters are all deep and well drawn out while remaining average, immature, angst-ridden teens. What really sets McKeever’s comic apart though is that he manages to perfectly capture how it feels to be a teenager and what most of us went through when we first started developing romantic feelings.

Appears in: A Superman for All Seasons #1-4. Collected in: A Superman for All Seasons graphic novel. A Superman for all seasons is a retelling of Superman’s beginnings, dealing with Clark Kent’s transition from a teenager in Smallvile to his early days as Superman in Metropolis. Each of the four books that make up the series is dedicated to a different season in which it takes place, and the ideas and symbolism of each season correspond to what Superman happens to be going through and what is happening in his life. The symbolism of the seasons and the cycle of nature is hardly new in literature, but luckily in this instance it’s handled well by a more than capable author. The end result is a coming of age story that’s rich in symbolism and themes and is also an entertaining read. The book was the main inspiration for the Smallville television show.

Appears in: The Sandman Presents: Lucifer #1-3, Lucifer #1-75, Lucifer: Nirvana #1-3. Collected in: Lucifer Vols 1-11. Lucifer is a spin-off of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman comic book centered around Gaiman’s interpretation of Satan, arguably the most interesting character in his book and one of the most interesting depictions of Satan since Paradise Lost. In Sandman, Lucifer realized he had been deceived, that he had never been the rebel he thought himself to be, but was instead nothing more than just a pawn in God’s master plan. So, to truly rebel, he quit as ruler of hell, kicking everyone out before he left. By the end of The Sandman comic book Lucifer was running a nightclub, Lux, in Los Angeles. Carey’s Lucifer picks up right where Gaiman leaves off, and initially the book seems to be largely modeled after Sandman, but very quickly it becomes clear that where Sandman took one of the powers of the universe and dealt with his day-to-day life and relationships, Lucifer is a true fantasy epic with larger than life characters involved in wars that will determine the fate of the universe. With its interesting characters and epic storylines Lucifer is a fun read. So much so, it seems like nothing more than a fun read, until you reach the end. And then you realize just how deep the work actually is, themed largely around the idea of predestination versus free will.

Appears in: Demon Annual #1, Demon #42-45, 52-54, Batman Chronicles #4, Hitman #1-60, JLA-Hitman #1-2. Tommy Monaghan is arguably the best hitman in Gotham City, although he only kills other criminals. After being infected with an alien engineered plague he gains x-ray vision and telepathy and decides to specialize in doing hits on other superhumans and demons. He first appears in Demon Annual, which is his origin story, and later appears in two other storylines in Demon. He then appears in Batman Chronicles before getting his own series. Several years later Ennis did a two-part JLA-Hitman miniseries that serves as a sort of epilogue. The earlier stories featuring Tommy in Demon are important to read because later stories draw on events that occur in them, but the story doesn’t start to hit its stride until Hitman #1. It’s hard to say exactly what Hitman’s about or what makes it stand out, because there are so many different things, most of which alone could have gotten Hitman on this list. The comic deals with characters deeply entrenched and moving through various crime syndicates in Gotham City, an aspect of the DC universe that is rarely seen. The characters themselves are for the most part ordinary people, often times commenting on popular culture and treating current events in the DC universe much the same as comic book fans (e.g. being upset over Superman’s long hair or making crude sexual remarks about Catwoman). The book de-glamorizes criminal life and has themes covering the inaccuracies of history, the nature of death, and how niceness and ethics are different from being a good person.

Appears in The Sandman #1-75, Annual #1, and the Sandman: Endless Night graphic novel. All but Endless Night are collected in Sandman Vols 1-10 The Sandman deals with the life and times of Dream of the Endless, one of seven immortal powers that act on the universe and routinely deal with gods, angels, demons, and other supernatural beings. Drawing heavily from the horror and suspense comics, Sandman paints a portrait of Dream through a series of seemingly disconnected stories, sometimes having Dream as the central protagonist, but other times having him do as little as a cameo appearance. However, the stories ultimately connect back together through various characters and themes. Another signature of Gaiman’s Sandman was pulling obscure characters from DC’s past and incorporating them into his stories. One of the first things that stands out about Sandman is it revolves around a being of epic stature, Dream, but the majority of the stories are centered around his personal life and relationships. From there The Sandman goes on to explore the ideas of stories, mythology, and folklore, their role in the world, and the role of the storyteller, and in doing so modernizes and retells many classic stories from mythology and history incorporating them into The Sandman universe. In the end the story deals specifically with character arcs and the necessity for change within our characters and within the universe.

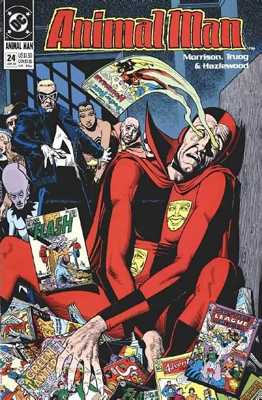

Appears in: Animal Man #1-26. Collected in: Animal Man Vols #1-3. Animal Man is an atypical superhero. He supports Green Peace, PETA, and animal rights in general. He wants to be a superhero and he wants to be able to make a living doing it, but he also dislikes violence. That isn’t to say that he’s against killing someone in a fit of vengeful rage, or accidentally joining a violent animal rights group. He isn’t even beyond something as simple as making a snap decision that he and his family are going vegetarian without thinking it through or even discussing it with his wife. Animal Man is a good and moral person with big ideals, but at the same time he’s far from perfect and, like most people, prone to making mistakes and letting his emotions take control of him. Morrison is known for being one of the writers to first introduce higher literary devices into comics. Animal Man is the first serious work of postmodern metafiction in mainstream comics. The Psycho Pirate is regurgitating old comics from our world in an attempt to bring back the characters erased from continuity during the Crisis on Infinite Earths. Animal Man takes peyote and sees the reader reading the comic. Ultimately Animal Man ends up on a quest to seek out what he rightfully believes to be his supreme being, Grant Morrison. Despite the fact that the book is very clear that it is just a comic book, the characters and their stories are still incredibly engaging and remain important to the reader. Plus if you can read the entire series and get through the final book without crying, you have no soul.

Appears in: Superman: Red Son #1-3. Collected in: Superman: Red Son graphic novel. What if Superman landed on Earth twelve hours later? Red Son takes place in an alternate universe where that has happened. Now instead of landing on a farm in Kansas and being raised to uphold truth, justice, and the American way of life, he lands on a Siberian farm and is raised to uphold the ideals of communism, the workers’ revolution, and Marxist philosophies. Lana Lang is a Siberian farm girl. Pete Ross is the illegitimate son of Stalin. And Bruce Wayne is an anti-Soviet terrorist. Meanwhile Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen, and Lex Luthor are all still born in the United States. Red Son is the first Superman work to question the idea of Superman. In the past, Lex Luthor has been allowed to express his views about how Superman is holding humanity back and that he is too powerful of a being, but only so that Superman could reveal Luthor’s perspective to be wrong and derived from pettiness. Red Son considers that Luthor may be right, and paints him as the hero. Meanwhile Superman’s character is largely unchanged, holding steadfast to a national philosophy that he considers righteous and moral and endeavoring to better the world and save lives, however he does so with a philosophy that the Western world has long since determined to be at best, unrealistic and oppressive, and at worst, evil.

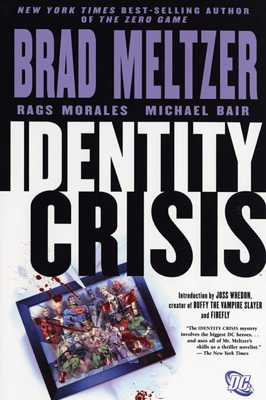

Appears in: Identity Crisis #1-7. Collected in: Identity Crisis graphic novel. Someone knows the secret identities of all the superheroes. Now they’re targeting and killing their loved ones. That is essentially the plot to Identity Crisis. Major DC heroes like Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman have small, almost cameo appearances in the story. The major characters are all lesser-known and less popular DC characters like the Elongated Man, Green Arrow, and the Atom. The story is a classic whodunit with the DC superheroes, and the reader, trying to figure out who would kill the families of superheroes and why. It also takes from modern crime dramas showing the superhero equivalent of CSI style investigations. But if you scratch the surface there’s a much deeper story hidden within identity crisis. A story centered on death, how it operates, what it does to us, and ultimately why the people we love have to die. The comic uses the rich and detailed history of the DC universe, its characters, and their relationships to fully make its points, a feat that couldn’t be accomplished without these already developed characters, some of which have existed for nearly eighty years. As much as that adds to the story, that is also the one major shortcoming of Identity Crisis. The story is so tied up in the DC characters and their histories that without a decent understanding of the DC universe many of the themes become lost, and at times the story is even difficult to follow.

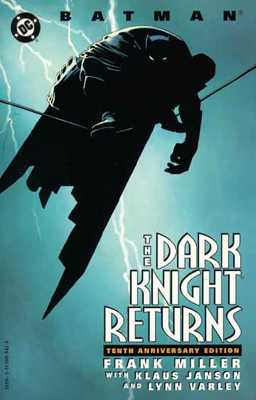

Appears in: The Dark Knight Returns #1-4. Collected in: The Dark Knight Returns graphic novel. People have gotten tired of superhero vigilantes. Superman is the last active hero, working in secret for the US government. The others have all retired of their own volition, or they’ve been forced into retirement by Superman. As the crime rate rises in Gotham City and Two-Face is released from prison, a 59 year old Bruce Wayne decides to come out of retirement and once again become Batman, ultimately leading to a fight to the death between Batman and Superman. Upon its release the comic was ill-received in the mainstream press because of its darker portrayals of Batman and Superman, but has since come to be regarded as not only one the of most important and influential Batman books, but one of the most important and influential comic books ever written. With The Dark Knight Returns, DC was once again trying to revitalize the popular Batman character for the modern era. In revamping the Batman character, Miller opted to show a more realistic version of Batman, but instead of changing Batman’s history for the sake of realism, Miller instead looked for reasons for Batman’s actions that made sense. For instance, he painted a bright target on his chest because he can’t put Kevlar on his head. Beyond simply deconstructing Batman though, the comic also explored deeper themes of how the role we’re meant to play changes as we grow older, elitism and the place superior people should hold in society, and the nature of superheroes and what they really mean to us.

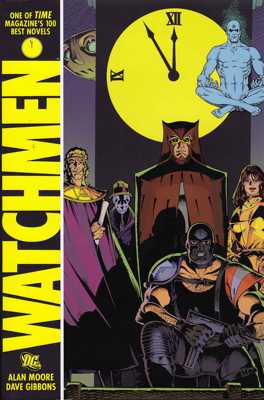

Appears in: The Watchmen #1-12. Collected in: The Watchmen graphic novel. How could any other title have made the number one spot? It is better regarded than any other comic book in history, it has won numerous awards, it was the only comic book included in Time’s list of the 100 greatest novels of all time, and it is the most popular work written by a man who is considered by most to be the greatest living comic book author. Moore started by taking the idea of what it would really be like if superheroes existed. What he ended up with was sexual deviancy, homosexuality, vigilantism, political and national exploitation, men and women who feel they are above the law and a public that ultimately scorns their existence. The work itself is meant as a deconstruction of the superhero story (and anybody who’s read a lot of criticism on literature or film knows that critics and academia alike adore deconstructions). Although it is the first real deconstruction of the superhero genre, that in and of itself is not that great of a feat. Moore however goes one step further and deconstructs Nietzsche’s superman; a philosophy, which more so than any other, has been tied into the idea of the superhero. Moore presents us with four different supermen, all conforming to Nietzsche ideal, and each following the ethics of a different school of philosophy. We then see what becomes of supermen when they exist outside theory or the idealized world typically found in comic books, and more importantly what they do to the society they exist in.