The question remains—king or kingmaker? Is it better to be the power figure or the one pulling the strings from the shadows? These next entries have never been household names, but their influence on history is undeniable.

10 Richard Neville, Earl Of Warwick

Richard Neville, 16th earl of Warwick, was the first to earn the epithet “Kingmaker” for helping to depose two kings during the Wars of the Roses. During the second half of the 15th century, both the Houses of Lancaster and York had a claim to the throne of England. This started a series of civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses. Initially, the Nevilles sided with the House of York, led by Richard, third duke of York. However, both the duke and the earl of Salisbury, Neville’s father, died in battle. This left Richard Neville and the duke’s son, Edward, as the people leading the Yorkist side. In 1461, they triumphed, and Edward became King Edward IV of England. Meanwhile, Neville’s power reached its apex as he inherited both his father’s and his mother’s possessions and received numerous titles from the king. A letter from the governor of Abbeville to King Louis XI of France exemplified who truly held the power in England. He said, “They have but two rulers—M. de Warwick and another whose name I have forgotten.”[1] The relationship soured when Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville instead of King Louis’s sister-in-law like Neville planned. Neville tried and failed to install Edward’s brother, George, to the throne, so instead, he switched sides to the Lancastrians and brought back Henry VI. Although initially successful, Edward reclaimed the throne in 1471 after Richard Neville was killed at the Battle of Barnet.

9 The Praetorian Guard

Ever since Augustus became the first emperor of Rome, the Praetorian Guard acted as the emperor’s personal security detail. They served in this position for over 300 years, and as the Guard’s power steadily grew, it became more and more corrupt. Although it was sworn to protect the emperor, the Praetorian Guard protected, first and foremost, its own interests. If a certain ruler went against those interests, praetorians had no qualms about assassinating the ones they’d vowed to defend. Over a dozen Roman emperors were murdered by the Guard, including Commodus, Caligula, and Aurelian. The greediness and corruption of the Guard reached their apex in AD 193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. They had just assassinated the last emperor, Pertinax, because he tried to institute reforms which included the restoration of discipline to the Praetorian Guard. With several claimants to the throne, the Guard decided to auction the imperial title by offering their support to the highest bidder. Didius Julianus won the throne by offering 25,000 sesterces per soldier.[2] He reigned for nine weeks before being executed. The Praetorian Guard came to an end in AD 312, when it was permanently dissolved by Constantine. The Guard supported Maxentius in a three-way fight for the throne. However, Constantine triumphed in decisive fashion and sent whatever praetorians were left to the far corners of the Roman Empire.

8 Ricimer

Flavius Ricimer was a general who effectively ruled for the last two decades of the Western Roman Empire by exercising his influence through puppet emperors. The son of a Suebi chief and a Visigoth princess, Ricimer could not ascend to the imperial throne. However, while serving in the military, he befriended Flavius Julius Majorianus, and in AD 457, he helped him become Majorian, emperor of Rome. In turn, the new ruler made Ricimer magister militum—master of the soldiers. After Majorian was defeated in a campaign against the Vandals, Ricimer convinced the Senate to turn against the emperor. Upon Majorian’s return to Italy, his magister militum had him arrested, tortured, and executed. In 461, Ricimer appointed Libius Severus as the new emperor of the Western Roman Empire. Severus died in 465, and it took almost two years before a new ruler was appointed. At this time, the faltering Western Empire was dependent on the Eastern Roman Empire for aid. Therefore, the eastern ruler, Leo I, had even more influence than the Germanic general. Eventually, the two compromised—Leo appointed Anthemius as the new emperor, but Ricimer joined his family by marrying his daughter.[3] In 472, Anthemius also failed against the Vandals and incurred the wrath of Ricimer, who went to war against him. The emperor was captured and beheaded and replaced with Olybrius. Ricimer died after a few weeks, followed by Olybrius later that year. What followed were a few years of short reigns before Odoacer proclaimed himself king of Italy, thus marking the end of the Western Roman Empire.

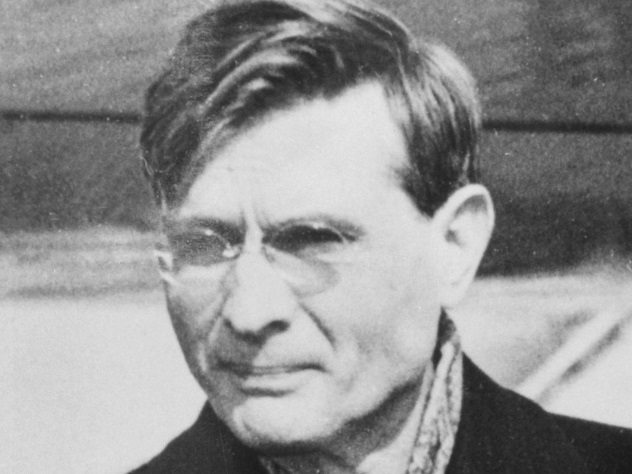

7 Mikhail Suslov

Known unofficially as the chief ideologue of the party, Mikhail Suslov was a Soviet statesman who maintained a high-ranking role within the Communist Party for over three decades until his death in 1982.[4] Under Stalin, Suslov quickly rose through the ranks. In 1941, he became a full member of the Central Committee of the Soviet Party and remained one for the rest of his life. He was named secretary in 1947 and elevated to the Politburo in 1952. Suslov saw a brief loss of power after Stalin’s death, when Nikita Khrushchev began his de-Stalinization process. However, he was back on top within a year, as the new Soviet leader needed an ideological expert like Suslov to help him justify his anti-Stalin campaign. Arguably, his first turn as kingmaker came in 1957, when Khrushchev was in a power struggle with the Anti-Party Group led by former premier Georgy Malenkov. Suslov lent his support to Khrushchev and helped him destroy the old Bolsheviks. However, seven years later, Suslov switched sides and played a key role in ousting the first secretary for political “adventurism.” Unofficially, some said that Suslov was first offered the leadership of the Soviet Union, but instead, he settled for the role of second secretary and advanced Leonid Brezhnev as a candidate. It can be argued that this actually provided him more control over the running of the Central Committee, as the Soviet ruler had to contend with international politics and official functions.

6 Carl Otto Morner

At the beginning of the 19th century, Sweden was facing a succession crisis. King Charles XIII was getting old and had no heir. He adopted Charles August, but the crown prince died of a stroke in 1810. Moreover, there was a real concern that Emperor Alexander I would invade in order to install a Russian candidate and turn Sweden into a puppet of the Russian Empire. As a result, a growing number of Sweden’s military and political elite believed that the wisest course of action was to name as heir a French marshal supported by Napoleon. Therefore, a Swedish delegation went to Paris to seek the emperor’s advice. The delegation’s junior member was a lieutenant named Carl Otto Morner. Although he was only a minor member of Sweden’s formal assembly, called the Riksdag, Morner took it upon himself to propose as heir a marshal named Jean Bernadotte. The move was considered so daring and outrageous that it almost got Morner arrested. His choice didn’t have the support of Napoleon because the emperor and the marshal were not on the best of terms. It didn’t even have the full support of Bernadotte himself, who was still apprehensive about the plan. At first, Napoleon refused to endorse or veto Bernadotte’s candidacy.[5] However, upon closer reflection, he eventually consented. Now that he had France’s support, the Swedish public began to warm up to Bernadotte, and the Riksdag unanimously elected him crown prince. He took the name Charles XIV and founded the House of Bernadotte, which still reigns today. Morner served as his advisor, retired as a colonel, and then became a deputy governor.

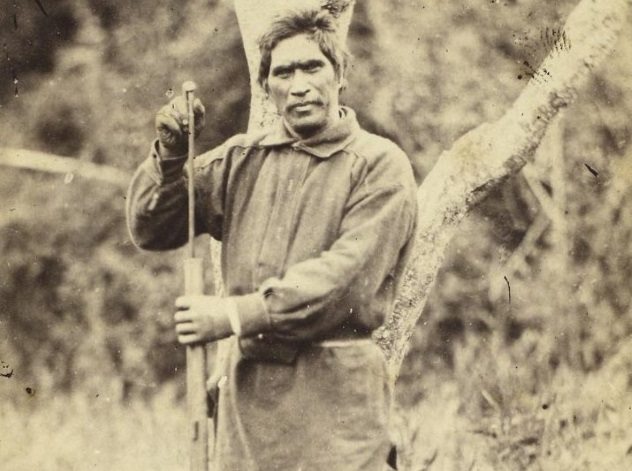

5 Wiremu Tamihana

During the 1850s, tensions were rising in New Zealand between Maori tribes (known as iwi) and white Europeans (called the Pakeha) over the latter’s continuous encroachment on indigenous Maori land. This prompted the Kingitanga, or Maori King Movement, which sought to unite the iwi under one monarch. Eventually, Waikato iwi chief Te Wherowhero became the first Maori king, but another man named Wiremu Tamihana was dubbed “kingmaker” by the Pakeha for his instrumental role in the movement. Leader of the Ngati Haua iwi, Tamihana was well-liked by the Pakeha for founding several flourishing Christian communities and trading with European settlers in Auckland. He was one of the main forces behind the Kingitanga and not only put forward Te Wherowhero as a candidate but convinced other iwi to accept his kingship. When the latter was confirmed as king in 1859, Tamihana placed a Bible on his head in a ritual which his descendants still perform on new Maori kings today.[6] Even with a newly elected king, the disputes between Maori and Pakeha led to an armed conflict known as the Taranaki Wars in 1860. Tamihana tried to act as mediator and sought a peaceful resolution, but other iwi leaders preferred to fight. The wars ended in a government victory, which led to significant confiscation of Maori land.

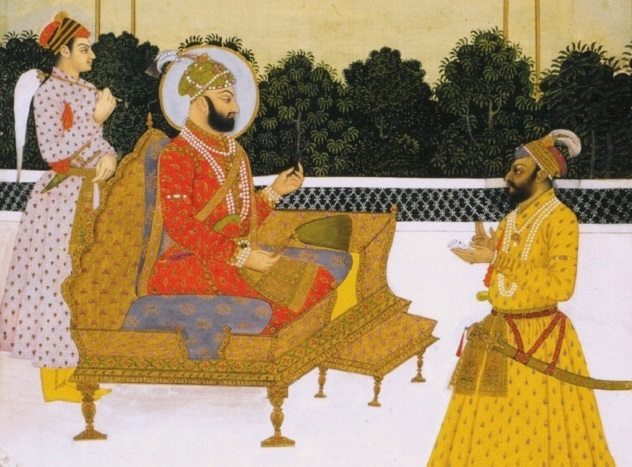

4 The Sayyid Brothers

By the time Emperor Aurangzeb died in 1707, he left the Mughal Empire a mighty domain which almost stretched over the entire Indian subcontinent. However, what followed was a series of short-lived reigns of emperors who were either crowned or deposed according to the interests of two highly influential courtiers—Hussain and Hassan Sayyid.[7] Aurangzeb’s successor was his son, Mu’azzam, who became Emperor Bahadur Shah. He ruled until 1712, after which he was succeeded by his son, Jahandar Shah. The new emperor’s reign was short, though, as he angered many people by elevating a dancing girl to the position of queen consort. The Sayyid brothers decided to back one of Jahandar’s nephews, Farrukhsiyar, who defeated his uncle at Agra and became emperor in 1713. Both brothers were given titles and high-ranking positions with the court. The relationship between the Sayyids and Farrukhsiyar deteriorated after a few years, as the emperor regularly sought out other advisors and left out the brothers. Eventually, this escalated to war in 1719. The Sayyids won, deposed Farrukhsiyar, and installed one of Bahadur’s grandsons, Rafi ud-Darajat, as the new emperor. He acted mainly as a puppet ruler as the Sayyid brothers became the true power brokers of the Mughal Empire. However, Rafi ud-Darajat ruled for roughly 100 days before dying. He was followed by his elder brother, Rafi ud-Daulah, who filled the same role. Unfortunately, he also died after 100 days. The new emperor was Muhammad Shah who, although young, had no interest in serving as a puppet for the Sayyid brothers. Instead, he gathered support from many disgruntled nobles and ended their reign by assassinating one sibling and defeating the other in battle.

3 Godwin, Earl Of Wessex

Between 1016 and 1035, Denmark, Norway, and England formed the short-lived North Sea Empire under King Cnut the Great. The empire collapsed with the king’s death, but those two decades saw the appearance of so-called “new nobles,” who managed to rise from relative obscurity to prominence at Cnut’s court. Chief among them was Godwin, who became the first earl of Wessex around 1020. After Cnut’s death, his son, Harold Harefoot, fought with Alfred, son of Ethelred the Unready, over the English throne. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Godwin conspired with Harold to lure the young prince to his death. First, the earl of Wessex professed his loyalty to Alfred and convinced him to go to London. He led him into an ambush in which Alfred’s men were killed, and the prince was blinded. He was sent to Ely Monastery, where he died shortly. Harold died in 1040 and was succeeded by his brother Harthacnut, who was also Alfred’s half-brother. Angered by the assassination, the new king had Harold’s body dug up, decapitated, and thrown in the sewer. Godwin managed to escape severe punishment by convincing Harthacnut that he was only following orders and providing a lavish ship as a gift. A new power struggle occurred in 1042, after Harthacnut’s death, between Magnus I of Norway and Edward the Confessor, son of Ethelred. Godwin’s support of Edward was considered crucial to securing the throne.[3] During Edward’s reign, the earl of Wessex was regarded as the second most powerful man after the king. His son, Harold Godwinson, became the new earl after Godwin’s death and later ascended to the throne when Edward died without an heir, thus becoming the last Anglo-Saxon king of England before the Norman invasion.

2 James Farley

US politician James Farley is probably most remembered today for a corruption scandal dubbed “Farley’s Follies.” While serving as postmaster general in 1933, Farley took preprints (un-gummed and imperforated sheets of stamps), autographed them, and gave them to acquaintances as gifts. When philatelists heard of his actions, they decried them as abuse of power, as Farley had used his position to gain access to new stamps and turn them into valuable rarities. Of course, this was just a minor episode in a career that spanned decades and saw Farley serve as advisor to dignitaries and politicians and even as chairman of Coca-Cola International. However, Farley’s greatest success was engineering four triumphant elections for Franklin D. Roosevelt. Farley and FDR met in 1924 at the Democratic National Convention. Four years later, Farley served as campaign manager for Roosevelt’s victorious gubernatorial candidacy. He did the same thing in 1930. In 1932 and 1936, Farley helped FDR get elected president of the United States. In return, Roosevelt named him postmaster general, chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, and chairman of the Democratic National Committee. It was at this time that people started recognizing James Farley’s tremendous clout and referred to him as “kingmaker,” something which annoyed the president.[9] The “king” and “kingmaker” had a falling out in 1940, when Roosevelt decided to run for a third term instead of supporting Farley’s presidential candidacy.

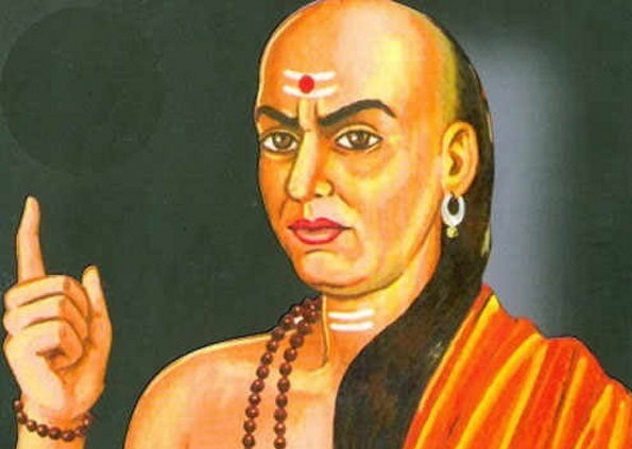

1 Chanakya

Chanakya, also identified as Kautilya, was a fourth-century BC philosopher who served as teacher and advisor to Chandragupta and helped him establish the largest empire on the Indian subcontinent. During Chanakya’s time, most of India consisted of smaller kingdoms called Mahajanapadas, except for the northern region, which was home to the Magadha Kingdom ruled by the Nanda dynasty. Most of the information we have on Chanakya comes from semilegendary accounts, so it’s hard to distinguish fact from fiction. However, they all agree that King Dhana Nanda insulted Chanakya somehow, and the philosopher swore that he would destroy the Nanda dynasty.[10] Chanakya aligned himself with the young Chandragupta Maurya, who may or may not have been orphaned and of noble lineage, depending on the source. The two slowly began to raise an army to challenge the ruling dynasty. The war itself is also poorly documented, referenced mostly in secondhand accounts from Roman and Greek historians. However, around 321 BC, Chandragupta overthrew the Nanda dynasty and became the first ruler of the Maurya Empire. He based his political and economical policies on the Arthashastra, an ancient Indian treatise typically attributed to Chanakya. So did his successors, including his grandson, Ashoka, who is credited with extending the empire and spreading Buddhism.