People writing notes or letters, putting them in bottles, and throwing them into the sea happens more than we think. These bottles are carried by ocean currents and end up in unimaginable places far away. Once opened, some changed lives, and others exposed secrets that were never meant to be known.

10 The Note That Exposed The British Ship That Refused To Rescue A Downed German Aircrew

The German Zeppelin L 19 (also known as LZ 54) was returning home from a bombing mission in the UK when it crashed into the North Sea in February 1916. A British trawler called King Stephen found L 19’s 16-man crew in the water but refused to help. The crew ultimately drowned. The incident would have remained unknown if one of the downed crewmen hadn’t written it in a note he put in a bottle and set loose in the ocean. The bottle contained two notes. The first was written by the Zeppelin’s captain, Oto Lowe, who wrote “February 2, towards 1 pm, will apparently be our last hour.” The second, which provided an account of the incident, was written by an unidentified crew member. It went: “My greetings to my wife and child. An English trawler was here and refused to take us on board. She was the King Stephen and hailed from Grimsby.” The bottle washed up on the shores of Sweden six months later. Germany used the note for propaganda, but the British media countered and reported that the captain of the King Stephen refused to help the German crew over fears that they might seize the ship. The bishop of London added fuel to fire when he said the actions of the British crew were “understandable.” An unimpressed German newspaper said the bishop “acted less as an apostle of Christian charity than as a jingoistic hate monger.”[1] Before the bottle was found, the King Stephen was sunk by a German U-boat. Its crew was rescued by the Germans, and they were held as prisoners of war until 1918, when they were returned to Britain.

9 An American Soldier Almost Found Love With A Letter In A Bottle Until The Press Came Along

During Christmas day in 1945, 21-year-old American soldier Frank Hayostek was returning to the US from France when he wrote a letter on a piece of paper, put it in a bottle, and threw it into the Atlantic, 1,300 kilometers (800 mi) from the US coast. The letter went: “I have no reward to offer the finder of this bottle as I am just a plain American with just enough to appreciate life and happiness. However, friendship is the only reward I can guarantee you.” The letter ended up in Lispole, Ireland, where it was picked up by Breda O’Sullivan, an 18-year-old milkmaid. Breda replied, Frank replied back, and both continued exchanging letters until Frank traveled to Ireland in 1952. Things went south from there. The media had gotten wind of the love story, and Frank’s trip to Ireland became a media sensation. In the end, the expected romance never happened, Frank returned to the US, and Breda stopped replying to his messages. Frank blamed the media for the failed relationship. Breda was a shy person, and the unexpected attention around her destroyed the possibility that anything would ever happen. Frank also added that Breda was not ready to leave her mother in Ireland and marry him in the US.[2] Breda also blamed the media for the failed relationship. She said she would not have even picked the bottle up if she knew she would have ended up in the news.

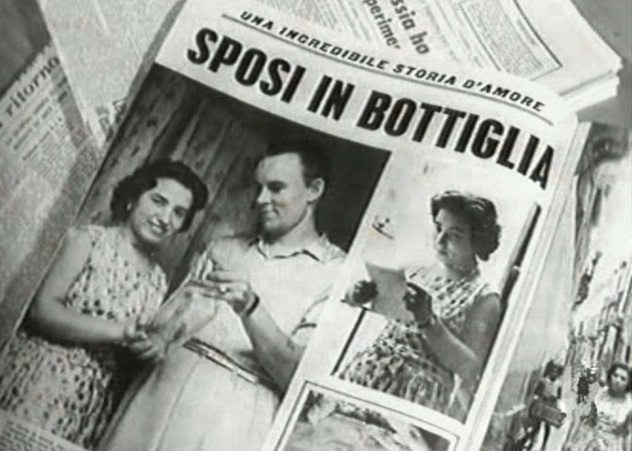

8 A Lady Married The Man Who Wrote A Letter She Found In A Bottle

Still on the subject of romance in a bottle, a man actually found his love after a lady replied to a letter he had written and set adrift. The man was Ake Viking, a sailor from Sweden, while the lady was Paolina, the daughter of a fisherman from Sicily. In 1955, Viking wrote a letter, put it in a bottle, and jettisoned it into the ocean. He titled the letter “To Someone Beautiful and Far Away” and included some information about himself. He added that any lady who found it should reply. The bottle ended up in Sicily, where Paolina’s father found it while fishing. He gave it to Paolina as a joke, but she replied. In the letter, Paolina told Viking she didn’t understand Swedish but was able to translate his letter with the help of her priest. She added that she wasn’t beautiful but decided to reply since the bottle had traveled far. Viking replied, and both continued exchanging letters back and forth until Viking traveled to Sicily to pay her a visit. They got married in 1958.[3]

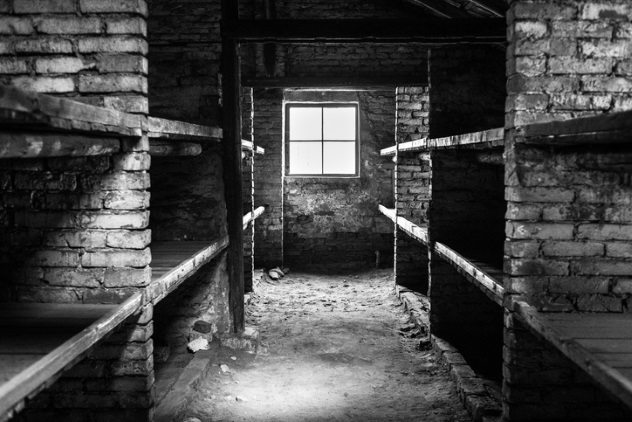

7 The Letter From Auschwitz

Not all messages in bottles were thrown into the ocean. One was found hidden inside the walls of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in 2009, 65 years after it was written. The letter was dated September 9, 1944, and was written by Bronislaw Jankowiak, a Catholic Pole who arrived the camp in 1943. Inside the letter, he mentioned six other men and gave a glimpse into their lives at the camp. Jankowiak died in 1997, but at least three of the men he mentioned in the letter were still alive when it was found. The men were Karol Czekalski, 83, Waclaw Sobczak, 84, and Albert Veissid, 84. Veissid was the only Jew in the group. The rest were Catholics. He was surprised that his name was included in the letter. He didn’t remember the men’s names but knew them by their faces. They met at the camp, where he helped them hide stolen provisions in exchange for soup. Prisoners at the camp were working on the wall at that time, and Jankowiak must have seized the opportunity to hide the bottle inside the wall.[4]

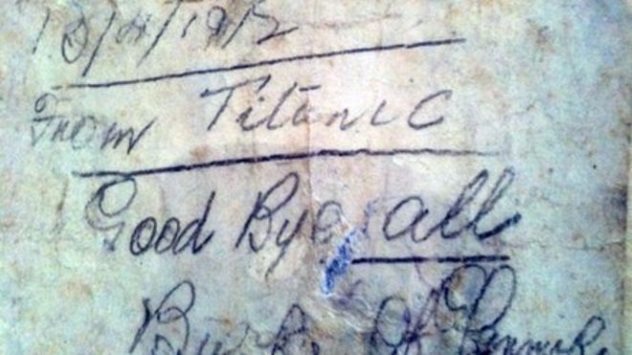

6 Jeremiah Burke’s Letter From The Sinking Titanic

Jeremiah Burke was one of the passengers on board the RMS Titanic as it sank in the early morning of April 15, 1912. The 19-year-old was traveling to New York with his 18-year-old cousin, Nora Hegarty. Both died in the disaster. As the Titanic sank, Burke quickly scribbled a letter and put it in a bottle. He tied one of his shoelaces to the bottle and threw it into the ocean. The letter reads “From Titanic, Good Bye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork.” The bottle ended up in Dunkettle, which is just few miles from his hometown of Glanmire, Cork, Ireland a year later. Burke’s death broke his mother’s heart, and she died within the year. She never got to see her son’s last message.[5]

5 The John Sands Mailboats

Mailboats were once used by the people of the Scottish archipelago of St. Kilda to communicate with the outside world. They weren’t messages in bottles per se, nor were they actual boats. Letters could be put inside anything so long it was watertight and could float. One mailboat found in 1904 was made of a sheepskin bag, a tin can, and cotton wool. Most mailboats end up along the coasts of the UK, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. St. Kilda was evacuated in 1930, but visitors and workers there still launch mailboats in keeping up with its legacy. Mailboats launched before 1930 also turn up at intervals. The first mailboats were launched in 1876 by John Sands, a journalist who was stuck on St. Kilda alongside some Austrian sailors. They were running out of food, and Sands, fearing they would starve to death, launched two mailboats, telling anyone who found them to inform the Austrian consul. The first was found in Orkney nine days later, and the second was found in Ross-Shire 22 days later. Both reached the Austrian consul, and a British ship picked the men up.[6]

4 Unidentified Passenger’s Note From The Sinking Lusitania

The RMS Lusitania was sunk off the coast of Ireland by German U boat U-20 on May 7, 1915, during World War I. The Lusitania was a civilian ship but had been targeted by Germany on suspicion of transporting weapons to Britain. Germany had announced unrestricted warfare against British ships and even paid for newspaper adverts warning Americans against traveling on British ships, as they could be sunk without warning. Lusitania left New York the day the first ads ran. Two explosions were heard on the Lusitania the day it was sunk. The first was clearly the torpedo, but the second remains a mystery. Germany said it was bombs cooking off. Whatever the cause of the second explosion, 1,198 people died in the mishap, while 761 were rescued. As the Lusitania sank, an unidentified person wrote a note but did not complete it before putting it in a bottle. The note reads: “Still on deck with a few people. The last boats have left. We are sinking fast. Some men near me are praying with a priest. The end is near. Maybe this note will . . . “[7] It is believed that whoever wrote the note stopped midway to put it inside the bottle just before the ship went completely underwater.

3 Oldest-Known Message In A Bottle

The oldest letter in a bottle that we know about was found north of Wedge Island, which is 180 kilometers (110 mi) north of Perth. The bottle was tossed into the Indian Ocean on June 12, 1886, by the crew of the German ship Paula. The Paula was part of a research project organized by the German Naval Observatory to understand ocean currents. The research ran from 1864 to 1933. Thousands of bottles were jettisoned into the ocean while the research lasted. The captain of the ship jettisoning the bottle was expected to include the date, coordinates, route, name, and home port of the ship in the letter inside the bottle. The Paula was 950 kilometers (590 mi) away from Australia and was sailing from Wales to what is now Indonesia at the time the bottle was jettisoned. At the back of letter is a note asking the finder to include the date and location the bottle was found and return it to the German Naval Observatory or any German consulate. Researchers believe the bottle washed up less than a year after it was thrown into the ocean but was buried in the sand until it was found in 2018. Before this, the last bottle found was in Denmark on January 7, 1934. This latest find is the 663rd bottle out of the thousands that were thrown into the ocean.[8]

2 The Letter That Got A South Vietnamese Soldier Into The US

On December 28, 1979, John Peckham and his wife Dottie were sailing from Acapulco, Mexico, to Hawaii when they wrote a letter, put it in a wine bottle, and threw it into the ocean. Inside the letter were their names, postbox number, and a message requesting that anyone who found the letter send it back to them. They added $1 to cover postage expenses. Three years and 14,500 kilometers (9,000 mi) later, Vietnamese refugee Nguyen Van Hoa found the bottle 16 kilometers (10 mi) off the coast of Thailand. Hoa had been a lieutenant in the South Vietnamese army and had fled Vietnam with his wife and brother after South Vietnam lost the war in 1975. He sent the letter back to the Peckhams, and both families continued exchanging letters for two years until Hoa requested that the Peckhams help him migrate to the US. The Peckhams agreed, and five years after finding the letter in the bottle, Hoa, his wife, his baby, and his brother arrived in Los Angeles.[9]

1 Private Thomas Hughes Died Two Days After Writing A Letter To His Wife, Who Never Received It

On September 9, 1914, Thomas Hughes, a private in the British Army, wrote a letter to his wife, Elizabeth, as he sailed to France to join in World War I. He kept the letter in a bottle and threw it into the ocean as his ship sailed through the English Channel. He added a note, requesting that anyone who found the bottle send the letter to his wife. In the letter, he wrote: Dear Wife, I am writing this note on this boat and dropping it into the sea just to see if it will reach you. If it does, sign this envelope on the right hand bottom corner where it says receipt. Put the date and hour of receipt and your name where it says signature and look after it well. Ta ta sweet, for the present. Your Hubby. Hughes was killed two days after writing the letter. Elizabeth never received it. She died in 1979, whereas the letter was only found in March 1999, 20 years after her death and 85 years after it was written. Fisherman Steve Gowan found the bottle in the River Thames. He delivered the letter to Thomas and Elizabeth’s daughter, Emily Crowhurst, who was already 86 years old. Emily was just two years old when her father left for the war.[10]