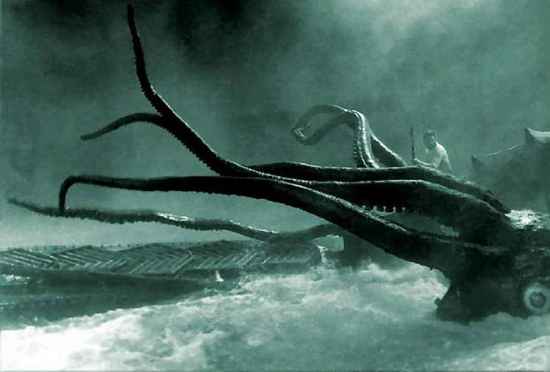

Captain Nemo’s underwater ship, Nautilus, is equipped with the world’s most adanced weaponry for the 1800s, including electrified bullets. But near the end of the novel, Nautilus is swarmed by a school of “poulpes,” which is the French word for “octopi.” It is almost always translated as “giant squid” because one pouple in particular becomes entangled in Nautilus’s propellers, and the crew has to go topside and battle it with axes, harpoons and knives. Verne never gives the squid’s size, but implies it, “one of these animals, only six feet long, would have tentacles 27 feet long. That would make a formidable monster.” While battling it, the squid manages to grab up one crewman and drown him, then devour him before the others chop off its entangling tentacles and drive it away. The real horror of this monster is that Verne was always interested in being realistic in his science fiction, and giant squids are real. We now have photographic evidence, and the largest species is believed to be at least 40 feet long, with the muscular strength to crush a crush a small schooner like a tin can. Its tentacles are lined with serrated teeth and sharp hooks that can slice human skin like a razor. They have the largest beak of all animals, large and strong enough to bite off a human hand. The largest recorded specimen weighed 1,091 pounds.

The minotaur is a cross between a human and a bull, and the story of its creation is a lot of fun. King Minos had a wife and queen named Pasiphae, whom Poseidon cursed with lust for a giant white bull he sent to Minos’s island, Crete. Pasiphae would dress provocatively and saunter past the bull, but the bull didn’t care at all. So she whined to her husband until he ordered Daedalus, his captive engineer, to build a huge, hollow bull for Pasiphae to climb into. She did so, they wheeled it into the bull’s pasture, and he promptly had his way with her. Their offspring was so monstrous and evil, devouring every human he could get his hands on. So Minos ordered Daedalus to construct a giant labyrinth in which the minotaur will be housed and unable to escape. In order to keep the minotaur from trying to find his way out, Minos orders 7 men and 7 women thrown into the labyrinth every year to keep the minotaur content. The minotaur is finally killed by Theseus, who uses a ball of thread given to him by Ariadne to find his way out of the labyrinth.

One of this lister’s favorites. The mythos surrounding this monster varies with each tribe of the Algonquian languages, among which tribes are the Cree, Ojibwa, Montagnais and others. As cited on Wikipedia is the Ojibwa description of the Wendigo: “Gaunt to the point of emaciation, its desiccated skin pulled tautly over its bones. With its bones pushing out against its skin, its complexion the ash gray of death, and its eyes pushed back deep into their sockets, the Wendigo looked like a gaunt skeleton recently disinterred from the grave. What lips it had were tattered and bloody [….] Unclean and suffering from suppurations of the flesh, the Wendigo gave off a strange and eerie odour of decay and decomposition, of death and corruption.” The Wendigo is a horrifying cannibalistic apparition that devours humans, and can assume their form in some of the tribes’ variations of the mythos. In all Algonquian tribes, any human who resorts to cannibalism will turn into a Wendigo forever. The best part of this mythos lies in the Abenaki tribe of Maine and Eastern Quebec. They feared the Wendigo because it would attack sleeping campers at night out in the wilderness (and Maine and Quebec have some very wild wildernesses), and cook and eat them feet first. Everyone in the area would hear the victims’ eerie distant screams.

Just one more reason not to like clowns. Tim Curry’s portrayal in the film version is outstanding, but the book is a hundred times better. This is King’s absolute pinnacle of scaring people. Pennywise is the name by which the monster goes when in the form it believes will entice most children to come near it. It has been around for millions of years and arrived on Earth from an extraterrestrial origin. It appears to a person in the form of whatever most terrifies him or her. If a person, especially a child, does not know, at first, to be afraid of it, it appears as a clown to lure the person closer. It hibernates for some 25-30 years and wakes up during some horrible catastrophe or act of violence. It assumes the form of anything it wants, in order to terrify human beings, especially children, whose fears are easy to manifest. But its most common disguise is as a clown carrying balloons that float against the wind. Its first scene is the infamous sewer scene, in which it stands up in a rainy sewer while little Georgie Denbrough is looking for his toy sailboat. Pennywise offers him the boat and balloons, and when Georgie reaches in to get it, Pennywise rips his arm out of the socket and devours it with horrible, ragged lion teeth. Georgie bleeds to death in the gutter screaming in agony. It appears later in life to Georgie’s brother, Bill, as Count Dracula with razorblades for teeth, and chops its jaws together on its own lips, slicing them open inches from his face in a library, just to horrify him. All it wants it to eat people, and people taste best when they are terrified. It delights in causing as much psychological, emotional and physical agony in people as it possibly can. The human mind can, only in terms of fear, approximate Pennywise’s true physical form. The most common human fear is arachnophobia, and thus, at the end, to the grown-up children who pursue it into the sewers, it appears as a very fast, gigantic, black spider with enormous fangs.

Scylla is also one of the great stories of Greek mythology, but Homer, whether man or committee, so popularized the monster that we think of it in Homeric terms. The story is a metaphor, similar to that of Daedalus and Icarus, for following the middle ground, and not veering too far one way or the other. In the Odyssey, Circe informs Odysseus that his route will take through the Strait of Scylla and Chraybdis. Charybdis is a huge whirlpool that will sink his ship. It will be better, thus, for him to sail closer to Scylla and lose a few men, rather than all of them. This he does, and Homer sings, “…gasping, they squirmed as Scylla swung them up her crag and into her cavernous mouth she gobbled them up raw, howling and flailing their arms at me.” Scylla’s appearance is horrid beyond reason: four eyes, six necks stretched long like hungry half-feathered chicks, huge, nasty heads, with three rows of ragged, shark teeth in each. Twelve tentacle legs and a cat’s tail with six dog heads blistered out around her waist.

Fenris (or Fenrir) is a colossal, shaggy black wolf, the offspring of Loki, god of mischief. According to the Heimskringla, and the Poetic and Prose Eddas, Fenris will attack and kill Odin himself, the king of the gods, during Ragnarok. Ragnarok is the Viking Armageddon, during which time, every single god and goddess will fight and die in battle. Almost all human beings will be destroyed in the turmoil, and the Universe itself wiped out and recreated anew by the All-father. Thor, god of thunder, will meet the cosmic midgard serpent, Jormungandr, who encircles the entire world and bites his own tail. When he releases his tail to fight Thor, Ragnarok will begin, and he and Thor will kill each other. Loki will fight Heimdallr, the horn god of wisdom, and they will kill each other. Fenris, meanwhile, is a huge wolf with a taste for human flesh. He grows ever larger with each person he devours, until, by the time of Ragnarok, he is the size of a continent or the whole world. His gaping lower jaw drags the ground while his upper jaw touches the sky. He fights and defeats Odin, then swallows him whole and alive. Then Odin’s son, Vithar, rips Fenris’s jaws apart and impales him. In some versions of the mythos, Fenris eats Odin, and then swallows the entire world before Vithar can stop him. Viking lore is so much fun.

Perhaps the purest entry on this list in terms of physical horror, Medusa is the daughter of sea gods Phorcys and Ceto, and in the original version of the mythos, she and her three sisters, also snake-haired and ugly, always existed in their monstrous form. It’s the late addition popularized by Ovid in his Metamorphoses that gives Medusa the backstory of once being so beautiful that Poseidon raped her in Athena’s temple. This infuriated Athena, who promptly transformed Medusa into a snake-haired hag so hideous that even looking into her eyes would turn any living thing into stone. This is where the saying “so scared I was petrified” etc. comes from. In most versions of the mythos, Medusa is beheaded by Perseus, who watches her mirror image in his shield to protect himself from looking at her.

Hard to say which is more horrifying, the Balrog, or Shelob, the giant spider (or Ungoliant, from The Silmarillion). Out of a desire not to repeat an author twice, this lister chose the Balrog and left Shelob off. Giant spiders are definitely not anyone’s idea of something to hug. But the Balrog is a gigantic demon that can shroud itself in undying fire, and wields a massive flaming whip, and a gargantuan flaming sword. It has claws of steel, and may have huge, bat-like wings of darkness. Tolkien appears never to have been satisfied with his creation, as he kept changing it, but the character in the Lord of the Rings is so powerful that no one in its 5,000 years of history in Middle-earth can overcome it, until it meets Gandalf. It survives the First Age War of Wrath and flees to the bottom of the Misty Mountains. In Third Age 1980, the dwarves mining mithril in the Mountains disturbed it, and all of them cobined could not defeat it, so they fled forever. Orcs and goblins moved in, sent by Sauron to secure the Mountains for his coming war, and the Balrog let them stay. They lived in absolute terror of it. When the Fellowship of the Ring became trapped by the orcs in 3019, Gandalf the Grey tried to thwart it with spells, only to discover that the Balrog knew counterspells. They faced on the Bridge of Khazad-dum, and it turns out that both Gandalf and the Balrog were Maiar, or lesser angels, and equally powerful. They both fell from the bridge, and fought in the bowels of the Mountains for 10 days, until Gandalf finally slew it and then died from wounds it inflicted on him. Shelob’s just a giant spider.

The first of three major villains in the anonymous epic poem. He is described as a descendant of Cain, the world’s first murderer, whose lineage God cursed with atrocious physical deformities. Grendel is never physically described in the poem except to say that he is a horrific creature, “very terrible to look upon.” He becomes enraged, probably by the people’s loud carousing every night in the mead hall of Heorot, and proceeds to break in during the festivities one night and devour 30 men. So King Hrothgar sends out word for Beowulf, the world’s greatest warrior, to come and kill the beast. With Beowulf and his men lying in wait, Grendel breaks in and gobbles up several of his men, then comes upon Beowulf, and they fight to the death. Beowulf rips one of his arms out with his bare hands, and Grendel flees nine days underwater to his mother’s lair. Beowulf goes after him, kills his mother, and finds Grendel cowering in a corner, and beheads him. Granted, Grendel’s a total wuss once he meets Beowulf, but until then, there’s no one in the world who can stop him.

He is a monstrous nightmare. The reason he is so horrifying is because of Carroll’s masterful description of him using blends (portmanteaus). He concocted new words throughout his famous poem, The Jabberwocky, to lend an air of nonsense, but with that nonsense comes fear. We are afraid of things we cannot sense. When the lights go out, you look over your shoulder at the drooling, horrifying monster you know is instantly panting behind you, ready to strip the flesh off your bones. Well, that’s the Jabberwocky. This lister always envisioned him as “the abominable snowman,” something like Bigfoot but whiter, covered in blood, with giant hawk-like claws, opened wide and ready to snatch you up into its horrible maw. Take the phrase “and the mome raths outgrabe.” Never mind what it means. It sounds violent, especially the sharp vowels in “raths” and “out.” Then the strikes of the consonant clusters “ths” and “tgr.” “Ths” sounds like a hiss. It has bright red eyes, a color that sticks out in a forest, and it “burbles,” which sounds just like the sound of drooling ravenously. “It came whiffling through the tulgey wood.” “Whiffling” is this lister’s favorite word in the poem. It implies light-footed speed, especially pertinent to a horrific beast that has just spied you and is sprinting, galloping as frantically as it can to rush upon you. What makes Carroll’s description masterful is how much he leaves out. That way, the reader makes up most of the image, and it’s always more horrid and terrifying that way. The whole poem exudes an abiding sense of dread, and the next time you take a walk in the woods and everything gets real quiet, you might wonder what’s immediately behind you, eyes wide and fangs drooling.