10 Elizabeth Branch

Elizabeth Branch was an 18th-century English widow who had a nasty reputation for cruelty to her servants. Born in Bristol, Elizabeth had a sizable fortune thanks to a generous dowry from her father, a former shipmaster, in addition to the income and estate of her husband, Benjamin Branch. It seems as though Elizabeth’s compulsions were somewhat kept in check while her husband was alive. Once Benjamin died in 1730, however, she not only began indulging her violent tendencies, but she also enlisted the help of her daughter, Betty. One day in 1740, the mother-daughter duo took their cruelty to new heights after becoming annoyed with their 13-year-old serving maid, Jane Buttersworth. The young girl went on an errand and took longer than expected to return. She tried to make up an excuse, but this only angered Branch even more, and she began beating the girl. Her daughter joined in. This was all done in front of the dairy maid, who later testified against the women at trial. The maid was forced to leave, and when she returned hours later, Jane was dead. Elizabeth brushed off her death as having been of natural causes and quickly had her buried. The locals, however, were suspicious enough to dig Jane up and send her body to the local surgeon. He ruled that the young maid had been beaten senseless, suffering multiple blows that could have proven fatal. At her trial, Elizabeth tried to bribe her way out, which resulted in a jury change. The second jury found both her and daughter guilty without leaving the room to deliberate.[1] Elizabeth and Betty were hanged on May 3.

9 Metta Fock

Swedish noblewoman Metta Fock was a convicted triple murderer who was executed in 1810 for killing her husband, son, and daughter. Although both Metta and her husband, Sergeant Henrik Johan Fock, came from noble families, they struggled with financial troubles. The sergeant allegedly suffered from diminished mental capacity, which led to costly mistakes as well as no advancement in rank. Rumors started that Metta was having an affair with gamekeeper Johan Fagercrantz. Then, in 1802, Henrik and two of the Fock children died within days of each other. People believed that Metta poisoned them with arsenic so that she could be with her lover. Fagercrantz confessed to the affair and was sentenced to 28 days living on bread and water. Metta was arrested and tried in 1805, alleging that her family had died of measles. Neither her nor the prosecution fully convinced the court, so Metta Fock wasn’t convicted but was ruled a danger to society. In accordance with Swedish law at the time, she was incarcerated until she confessed. Metta Fock became the only woman imprisoned in Carlsten Fortress.[2] She eventually confessed in 1809 and was executed by decapitation and burning. Modern scholars have suggested the idea that Metta Fock might have indeed been innocent and that her family died during a measles outbreak. Her arrest and her trial could have been influenced by Baron Adam Fock, patriarch of the family, who wanted to see her convicted.

8 Grete Beier

Born in 1885, Marie Margarethe (Grete) Beier was the daughter of the mayor of Brand in Saxony, Germany. Unsurprisingly, her childhood benefited from the exclusive education and upbringing that her position afforded her. When she turned 22 years old, her parents sought to enhance her status even more by marrying Grete to a successful engineer named Heinrich Pressler. Grete, however, already had a lover named Johannes Merker, and she had no intention of breaking up with him. At the same time, though, she also didn’t want to give up her lifestyle, so her next move became obvious: Murder her fiance and get his money. On May 13, 1907, Grete went to visit her soon-to-be husband and poisoned his drink with cyanide. Afterward, she stuck a revolver in his mouth and blew his brains out and then proceeded to make his death look like suicide. She forged a suicide note as well as several love letters between Pressler and a fictional Italian woman who was threatening to expose their affair.[3] Beier also wrote a new will for Pressler, hoping to make it look as if the engineer killed himself and left his money to his fiancee to make up for the shame caused by the affair. Grete almost pulled it off. While the coroner ruled Pressler’s death a suicide, police were more suspicious of the convenient will and watched Beier for several weeks before uncovering her plan. The girl with “the face of an angel and the heart of a fiend” was executed by guillotine in Freiburg Prison.

7 Philip Henry Cross

In the late 19th century, Dr. Philip Henry Cross and his family retired at his ancestral home, Shandy Hall, located near Coachford in County Cork, Ireland. Prior to this, Cross had worked as a surgeon for the British Army and had been stationed in Canada, where he married Mary Laura Marriott in 1869. When he left the army, the family moved back to Ireland, where the Cross bloodline had roots going back three centuries. Philip gained a fortune courtesy of Mary’s inheritance. The two had six children together and soon hired a governess named Effie Skinner (pictured above with Cross) to look after their youngest daughter. However, Mary soon started suspecting that her husband had developed feelings for the nanny and sent her away in January 1887. Effie returned six months later, though, this time as the new Mrs. Cross: The old one was dead and buried. After Effie left, the doctor diagnosed his wife with typhoid and began “treatment,” which was poisoning her with arsenic.[4] After she died, he arranged a speedy funeral, citing the contagious nature of the disease. He married Effie 15 days later. Unsurprisingly, this aroused a lot of suspicion. After exhuming and examining Mary’s body, police found traces of arsenic but no signs of typhoid. The doctor was charged with murder and hanged in 1888.

6 Jean Kincaid

Jean Kincaid was born Jean Livingston in 1579 in Scotland. Her father was John Livingston of Dunipace, and she later married into the Clan Kincaid of Stirlingshire, becoming Lady Warriston. However, despite her growing influence and wealth, Jean’s marriage to John Kincaid was not a happy one. According to Jean and her servants, John mistreated and abused her, both physically and mentally. Soon enough, Jean began to hate her husband, and on the advice of her nurse, she plotted to have him killed. She sent out the nurse to enlist the help of Robert Weir, one of her father’s servants and (according to rumors) her lover. When Weir arrived at the Kincaid estate, he hid in the cellar until John was asleep. Jean brought Weir to the bedroom, where he struck her husband with a blow to the head and then strangled him. Weir was willing to go on the run and take the blame for the crime on his own, even though Jean wanted to accompany him. He was captured four years later and executed on the breaking wheel. As far as Jean Kincaid was concerned, nobody believed she was innocent in the matter. She was arrested along with her nurse and two female servants and brought to trial on July 3, 1600, just two days after John’s death. The trial lasted less than three hours, and all were found guilty. The accomplices were strangled and burned, and Lady Warriston, being a noblewoman, was beheaded.[5]

5 Elizabeth Jeffries

Born in 1727, Elizabeth Jeffries was orphaned at an early age. When she was five, Elizabeth was adopted by her rich uncle, Joseph, who took her to live with him on his estate in Walthamstow, Essex. Joseph had no children of his own, so he willed his fortune to Elizabeth on the condition that she maintained good behavior. This was something that went against the young woman’s nature, and in the end, her uncle threatened to cut her out of the will. Worried that her uncle might go through with his threat, Elizabeth decided to kill him. She enlisted the help of his gardener, John Swan, who was also thought to be her lover. The two also hired another servant named Matthews, although it was later revealed that the pair planned to frame him with the crime. On the night of July 3, 1751, Matthews was supposed to shoot his employer. He hid in a pantry until night came, but he got cold feet and backed out.[6] Eventually, Elizabeth and Swan did the deed themselves. They then tried to make it look like a botched robbery and implicated Matthews. This turned out to be a mistake because Matthews was captured and promptly told the truth regarding the murder. Authorities suspected Elizabeth, anyway, and now they had the evidence to arrest her. Both she and Swan were found guilty and hanged in 1752.

4 Francoise De Dreux

Back in the late 17th century, France was shocked by a scandal involving a poisoning ring surrounding a woman named Catherine Montvoisin, aka “La Voisin.” It became known as the Affair of the Poisons. The outrage intensified when it became clear that many of Montvoisin’s clients were part of France’s aristocracy, even people close to King Louis XIV. Francoise de Dreux was one of those clients. Specifically, she was the wife of a member of Paris’s parlement and was accused of poisoning at least three people. She also tried to kill her own husband and the wife of one of her lovers, the duke of Richelieu.[7] Despite this, Madame de Dreux was acquitted due to her status and the fact that two judges at her trial were her cousins. This didn’t sit well with the public, as many others involved in the scandal who weren’t nobles were promptly executed for far lesser crimes. Undeterred by her narrow escape, Madame de Dreux was ready to resume her criminal activities. She was only stopped by the fact that her go-to poisoner, Marguerite Joly, was arrested and executed—but not before further implicating de Dreux. Francoise was tipped off that her arrest was imminent and fled the country in 1681. Eventually, her husband lessened the punishment to exile from the capital. After a couple of years, even that got dropped, and Madame de Dreux was allowed to return to Paris to live under her husband’s supervision.

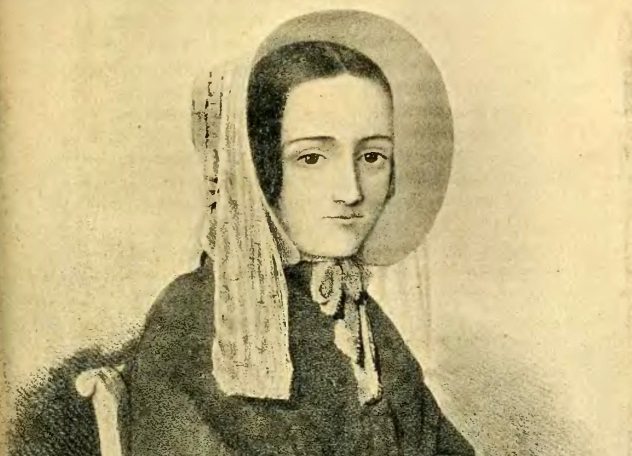

3 Marie Lafarge

In 1840, Marie Lafarge was accused of poisoning her husband with arsenic. Her case received extensive coverage in the daily newspapers not only due to Lafarge’s high profile but also because of the pioneering forensic toxicological evidence used in the trial. Marie’s motive was anger and disillusionment directed at her husband. She was the daughter of an artillery officer and reportedly a descendant of Louis XIII. She married Charles Lafarge in 1839 because he claimed to have a massive estate and a thriving business as an iron master. In truth, though, the estate was a former monastery fallen into disrepair, and the foundry was only kept open through loans from creditors. A profitable marriage was the only way for Charles to avoid bankruptcy. During Marie’s trial, local pathologists were asked to do a postmortem examination of Lafarge’s body and check for traces of arsenic. Not familiar with the latest forensic developments, the doctors provided inconclusive results. In the end, the prosecution requested the aid of leading toxicologist Mathieu Orfila, who showed that Marie poisoned her husband. In response, the defense planned to bring in their own expert chemist: Orfila’s nemesis Francois Raspail.[8] Raspail couldn’t arrive in time, though, and Marie Lafarge was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. However, Raspail openly challenged Orfila’s methods and published several papers contesting his results. Many people, including author George Sand, sided with him and believe that Marie was unjustly imprisoned.

2 Beatrice Cenci

Even though Beatrice Cenci died over 400 years ago, her legend still haunts Rome to this day. It is said that her ghost returns every year on the eve of the anniversary of her death, prowling the bridge where she was executed, carrying her severed head. Even without the added theatrics, Beatrice’s tragic story is a compelling one. Her tale of cruelty and murder has provided inspiration for countless artists, including Alexandre Dumas, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Stendhal. Born into one of Rome’s noble families in 1577, Beatrice was the daughter of Francesco Cenci, a violent, sadistic aristocrat who used most of his influence and wealth to avoid prison for his various evil deeds. Beatrice’s older siblings escaped their father’s reach as soon as possible. In 1599, the only ones who still had to endure Francesco’s wrath were Beatrice and his second wife, Lucrezia, along with her young son Bernardo. The nobleman imprisoned them in the family castle near the village of Petrella Salto, where his cruelty intensified away from prying eyes. Eventually, the Cencis had enough and decided Francesco had to die. Beatrice enlisted the help of her brother, Giacomo. First, they tried to poison Francesco, and then they bludgeoned him with a hammer. They threw him off a balcony to make his death look like an accident. Despite their efforts, all four Cencis were found guilty of murder. Beatrice and Lucrezia were taken to Sant’Angelo Bridge, where they were beheaded, while Giacomo was drawn and quartered, and Bernardo was sold into slavery.[9]

1 Lewis Hutchinson

Sometime during the 1760s, Scottish doctor Lewis Hutchinson immigrated to Jamaica. He took up residence in an estate in Saint Ann Parish called Edinburgh Castle. He also became Jamaica’s first recorded—and to this day one of its most prolific—serial killers. Hutchinson, also known as the Mad Doctor or the Mad Master of Edinburgh Castle, developed such a wicked reputation that it is difficult to separate legend from fact. It appears that he tortured and killed purely for pleasure and enlisted the aid of several slaves and servants. His estate was the only inhabited place for miles, so travelers were doomed once they stopped by Edinburgh Castle to rest. The lucky ones would die with a quick bullet, but locals said that afterward, Hutchinson liked to dismember his victims and feast on their blood. The remains were often tossed in a sinkhole, which is still known today as Hutchinson’s Hole. Allegedly, the Mad Doctor was so feared that although many locals knew of his evil doings, they were too afraid to do anything about it and avoided him at all costs. Eventually, a British soldier named John Callendar went after Hutchinson and was promptly gunned down.[10] This murder sent Hutchinson fleeing, with the Royal Navy on his tail led by Lord Rodney. Hutchinson was captured, found guilty, and hanged alongside several accomplices.