However, when a famous and rare artifact falls under the hammer, there is an expectancy that somebody will buy it. This is not always the case. Unique and history-altering artifacts can go unclaimed, even lots identical to items that sold for millions at other auctions.

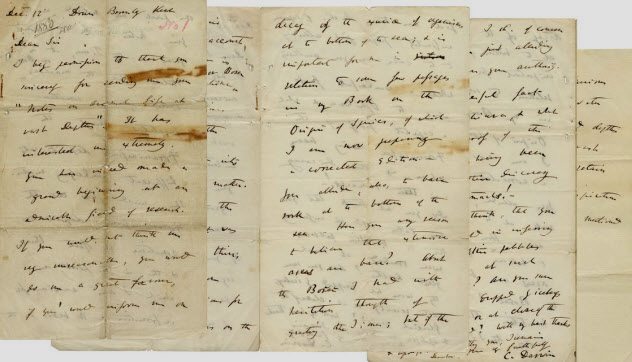

10 Rare Darwin Letter

Letters written by the famous naturalist Charles Darwin have market appeal. A four-page correspondence with his niece fetched $59,142, and somebody shelled out $197,000 to own a letter in which Darwin penned his doubts about the Bible. When Nate D. Sanders Auctions made another document available, they expected a sale. Put up for auction in 2016, a year after the record-smashing Bible letter, the new one had promise. It was rare, handwritten, and signed by Darwin on December 12, 1860. British author and biologist George Wallich had sent the naturalist his book about deep-sea life. The letter was written to thank Wallich, but it was not merely a polite response. Darwin was greatly affected by Wallich’s research and grilled him for information about starfish, basaltic pebbles, and foraminifera (single-celled creatures with shells). The letter also mentioned that Darwin planned to publish a corrected version of his book, On the Origin of Species, which had been released a year earlier. The words show Darwin at his best—a passionate researcher fascinated by the devil in the details. Valued at a reserve price (the lowest bid allowed) of $69,500, there were no takers.[1]

9 The Dueling Dinosaurs

At the Chicago Field Museum stands the iconic T. rex fossil named Sue. In 1997, the museum paid $8.36 million after bidding was not expected to pass $1 million. Then the Montana badlands produced bones expected to beat Sue’s record performance for dinosaurs at auction. The remains belonged to a pair of intertwined dinosaurs—a new ceratopsian herbivore and a tyrannosaurus-like predator. Their positions suggest that they were fighting when a landslide entombed them. Their value stems partially from the unusual picture they make. These are also the most complete specimens from North America’s Late Cretaceous and are so well-preserved that bits of skin remain. With great interest from museums and the public, the “dueling dinosaurs” came under the hammer in 2013. Bonhams auction house held the event in New York and opened the bidding at $3 million. The auctioneer maneuvered the amount up to $5.5 million but no further.[2] Museums could not rise to the estimated $7 million to $9 million predicted as the ceiling. The highest bid failed to match or overtake the fossils’ mystery reserve price, and the auction ended without a buyer.

8 The Cook Waistcoat

Captain James Cook is well remembered as a famous explorer. In 1770, Cook seized Australia in the name of Britain, and nine years later, he was stabbed to death in Hawaii during a skirmish with locals. One of his waistcoats survived. Originally, it was in the possession of his family, but it passed to an antiques dealer who sold it in 1912. The buyer, a British industrialist, gifted it to the famous Australian pianist, Ruby Rich. She altered the beautifully embroidered waistcoat to suit a woman’s body and wore it to social functions. A private collector purchased the garment from the Rich family in 1981 and, in 2017, put it up for auction. Considered to be one of the most significant Cook pieces, the 250-year-old waistcoat was valued between A$800,000 and A$1.1 million. During the auction, which was held in Sydney, bids rose to what some might consider a handsome amount—A$575,000. However, this was too little considering the waistcoat’s worth and the sale fell through.[3]

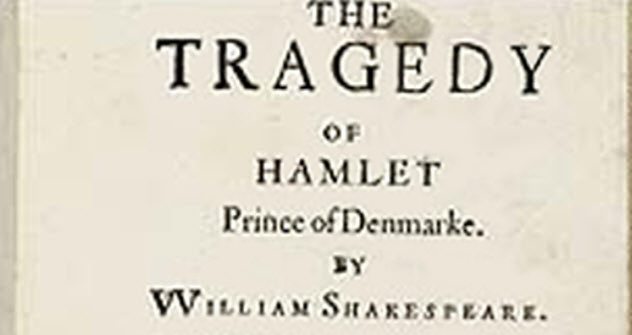

7 First Edition Hamlet

During her lifetime, the Viscountess Mary Eccles indulged in a passion for old books. For more than 60 years, she built an incredible library at her home in New Jersey. When she died in 2003, her collection was made available by the auction house Christie’s a year later. Consisting mainly of 17th- and 18th-century books, it included a copy of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This rare first edition was printed in 1611 when Shakespeare was still alive. It was also the oldest to be privately owned. Since the Eccles library was one of the most valuable in recent times, it attracted many potential buyers to the New York event. The collection included other works by Shakespeare, and they all sold. In fact, 98 percent of the entire Eccles collection found new shelves. One surprising lot that failed to sell was the Hamlet. Christie’s admitted that they may have been overly optimistic by expecting the book to provoke bids as high as $2 million. But who can blame them? Three years earlier, another first edition Hamlet from the 17th century fetched £3.4 million.[4]

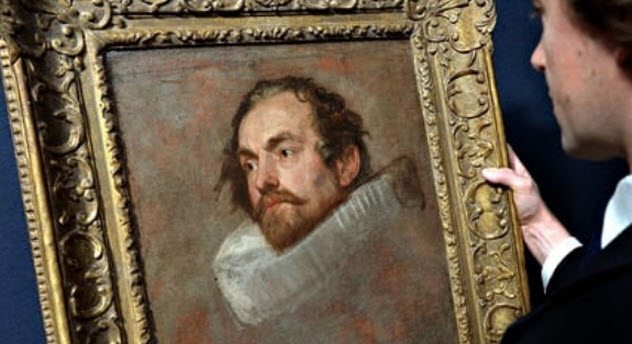

6 The Missing Van Dyck

Another rare 17th-century antique handled by Christie’s was a painting by the Flemish master Van Dyck. Its modern story began like a hopeful fairy tale for the owner. In 1992, Father Jamie MacLeod found the picture in a Cheshire shop and bought it for £400. It hung in his hallway for years. Then the popular show Antiques Roadshow visited and identified the work as an exceptional Van Dyck. The so-called Head Study of a Man in a Ruff is part of a trio named The Magistrates of Brussels. They hung in the town hall of Brussels until the building was leveled by the French in 1695.[5] The rediscovery completes the rest of the collection currently kept at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Told that the oil portrait could collect up to £500,000, the priest planned to buy new bells for the town church. However, nobody snatched up the painting when Christie’s auctioned it in 2014.

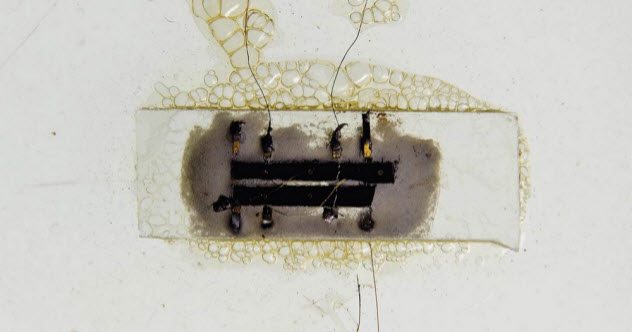

5 World’s First Microchip

In 1958, an unknown Jack Kilby made an odd-looking brick and changed life as we know it. The Texas Instruments worker had created the first microchip. The handmade icon does not have the looks to match its fame. The unassuming chip is a germanium wafer sprouting gold wiring, set on a sheet of glass, and enclosed in plastic. The primitive integrated circuit also walked away with the most sought-after trophy among scholars. In 2000, Kilby won the Nobel Prize in physics for his work. Recently, the chip was part of a lot at a Christie’s auction. Included in the lot were two additional items complementing the historic chip. There was a later, more stable prototype and a letter written by Kilby in 1964 that explained how the chips functioned. The highest bid for the set was $850,000. Again, it was a case of failing to meet the reserve. Christie’s, which gauged a winning bid at $1 million to $2 million, stopped the sale.[6]

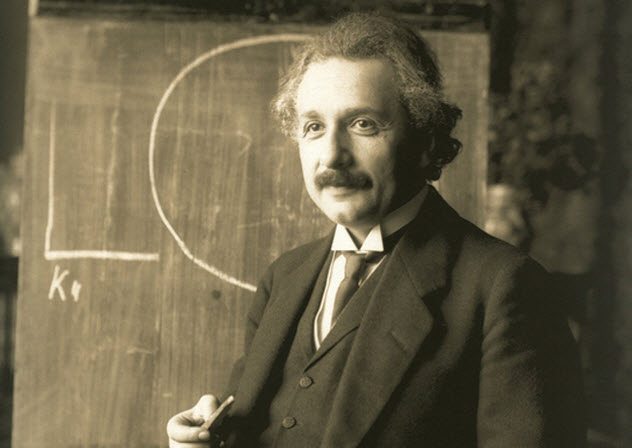

4 Earliest Relativity Manuscript

Seven years after renowned physicist Albert Einstein released his special theory of relativity, he penned a related document. Written in 1912, the 72-page work is the earliest and biggest paper Einstein created on the subject. Since it remained unpublished, precious few knew it existed. In 1987, it appeared in public for the first time. It passed from Professor Erich Marx as an inheritance to a descendant who auctioned it through Sotheby’s for $1.2 million. Despite those who said nothing new could be gleaned from the paper, its value was not purely academic. It provides personal insight into Einstein’s approach for his later theory on general relativity. Most remarkably, Einstein wrote “EL=mc2” in the manuscript and crossed out the L.[7] This showed how he arrived at what is perhaps his most quoted equation. When Sotheby’s auctioned it for a second time in 1996, the room was packed. However, the anonymous owner refused the highest offer of $3.3 million. Another mystery reserve blocked the sale, which was expected to fetch at least $4 million.

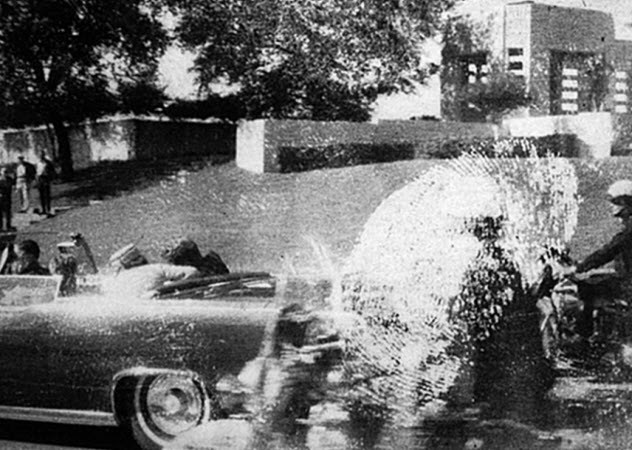

3 JFK Assassination Photos

On November 22, 1963, a housewife went to downtown Dallas because she wanted to see Jackie Kennedy. Mary Ann Moorman took her Polaroid camera and found a nice spot. When the presidential motorcade went past, she snapped two photos. The first was of Glenn McBride, an officer with the motorcycle guard. The second image captured the seconds after or possibly even the moment that President Kennedy was first shot. The historic photo became widely known as the “grassy knoll” picture and remains the only one to show both the knoll area and the president’s car. The original Polaroids remained with Moorman until recent years when she approached Sotheby’s. The auction house declined to sell them after the Kennedy family voiced their disapproval. In 2013, the now 81-year-old photographer partnered with Cowan’s Auctions in Cincinnati. They valued the prints between $50,000 and $75,000 and auctioned them a week prior to the 50th anniversary of JFK’s death. The lot failed to sell but did not lose its fans. Although nobody met the reserve, several potential buyers entered into post-auction negotiations with Cowan’s.[8]

2 The MacDonald Stradivarius

A Stradivarius is the holy grail among stringed instruments. Considered to be the unbeaten “gold standard,” around 600 of these instruments made by Antonio Stradivari survive today. Only 10 are violas, which make them very rare. Violas look like violins but are bigger and produce a deeper sound. The best viola is the MacDonald Stradivarius, and it came up for auction at Sotheby’s in 2014. Two other Strads were auctioned earlier, and only one returned a stellar performance. Three years before, the “Lady Blunt” violin, made in 1721, shattered the record for any musical instrument when it sold for $15.9 million. A month before the MacDonald auction, another viola was offered by Christie’s without success. The “MacDonald” viola was created by Stradivari two years before the record-breaking violin. A presale estimate suggested that it would surpass the violin and fetch around $45 million. Unfortunately, it flopped like the other viola.[9]

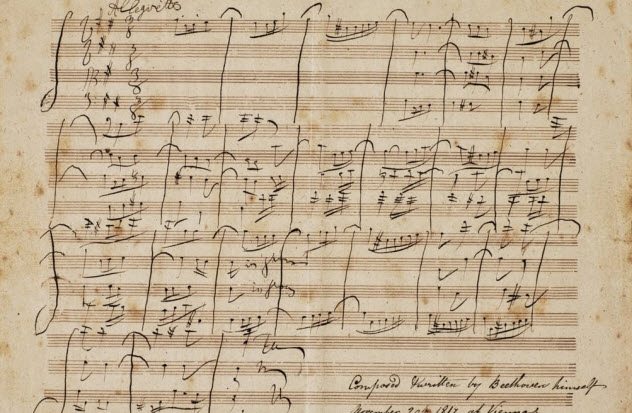

1 The Disputed Beethoven

When a lot underperforms, the reason is not always lack of interest or a purse too small. Sometimes, it is a public spat between the experts and an auction house. In 2016, Sotheby’s held a score by composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827). It was expected to garner around £200,000. Unfortunately, Sotheby’s crossed swords with a Beethoven scholar on a radio program. Professor Barry Cooper insisted that Allegretto in B minor was the work of an inept copyist and not penned by the hand of Beethoven, as claimed by Sotheby’s. The single page is signed “composed and written by Beethoven himself November 29 1817 at Vienna.” However, the phrase was not written by the composer but by an English vicar whose descendants kept the artifact. Sotheby’s said that specialists verified the document and that Cooper refused to view it in person. Cooper, who has 40 years of experience working with Beethoven manuscripts, studied a photocopy. He pointed out mistakes that Beethoven would never have made.[10] Also, while Sotheby’s experts remained unnamed, Cooper named scholars who believed him. One, a respected Beethoven expert named Jonathan Del Mar, viewed the score up close and was unconvinced of its authenticity. The strife between the auction house and Cooper was cited as the main reason when the sheet’s auction was a dismal failure. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages