Societies older than the Maya knew about magnetism, turkeys were gods, and nearly the whole Mesoamerica knew how to get high. The Maya also invented the papaya we eat today. Then there were the friends of the Aztecs who ate the conquistadors.

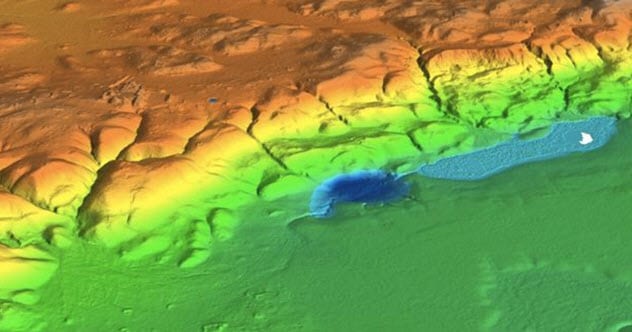

10 A New Sacred Lake

In 2018, Polish archaeologists and divers teamed up with Guatemalan scientists. Their focus was the Lake Peten Itza. At one time, it encircled a Mayan city called Nojpeten. Undoubtedly, the location was chosen to provide the city with water, but researchers thought there might be more to the choice. The Maya treated water, especially lakes and flooded sinkholes, as doorways to the afterlife where the gods dwelled. As a result, Mayan sacrifices often occurred in water. The lake gave plenty to prove it was once sacred. Divers returned from the depths with over 800 artifacts. Most were fragments. The intact pieces included three ceremonial bowls stacked inside each other. Tiny animal bones nestled within, but it cannot be said whether they were sacrificed or creatures that perished at the location later. However, an obsidian blade was recovered and the type had been previously linked to sacrifices. The artifacts dated from 150 BC to AD 1697, a good indication that the lake was sacred for centuries. To gather more information, the Polish and Guatemalan teams plan to meet each year to explore the site for a month.[1]

9 The Tomb That Was A Bath

The Mayan city Nakum once stood in Guatemala. A few years ago, archaeologists at the site stumbled upon a cave-like room. As they rolled up their sleeves, the team assumed that they were clearing a tomb. It did not take long for the assumption to shatter. The room was not a tomb. Instead, it was one of the oldest steam baths from Mesoamerica. These Mayan structures were used for spiritual and relaxation purposes, but few survived intact. The Nakum bath was exceptional in this sense. The complex was relatively undamaged. Everything was hewed from limestone, including the seats and a hearth that heated rocks to turn water into steam. A tunnel sloped downward to guide excess water from the bath to the exit. This feature came with stairs, allowing visitors to approach the bath from two directions. After being in use for nearly 400 years, it was filled with rubble and sealed in 300 BC.[2]

8 A Rare Pyramid Burial

Around 2,700 years ago, a pyramid was built in southern Mexico. When archaeologists investigated the structure in 2010, they identified the builders as the Zoque Indians. Located at the ancient site of Chiapa de Corzo, the pyramid turned out to be a tomb. Not only was it possibly the oldest pyramid grave in Mesoamerica but it was also not a common grave. Pre-Hispanic civilizations preferred their pyramids as religious sites and temples, not cemeteries. Inside was the body of a man. Valuable artifacts made from jade, obsidian, and pearl showed that he had enjoyed a high status in life before dying around age 50. His role remains unknown, but the grave goods suggested a leader or priest at Chiapa. The man was not alone. An infant had been carefully arranged on top of him, and a nearby tomb held a woman his own age. The scene was not entirely peaceful. The death of the dignitary probably cost a young man his life. The remains of a 20-year-old male rested awkwardly as if he had been tossed inside as a sacrifice.[3]

7 Turkeys Were Gods

Turkey is a favorite sandwich filling. The bird’s status was starkly different from 300 BC to AD 1500 when turkey farming started in Mesoamerica. Scientists examined the bones of 55 ancient turkeys in 2018 and realized that the birds were never raised on the large scale necessary to appear on the Mayan and Aztec menus. Their remains also rarely turn up in Mesoamerican house trash.[4] Instead, turkeys were buried in temples and accompanied the dead in their graves. Mayan iconography showed the birds as gods. It could not be clearer. These were among the first turkeys that humans domesticated, but the effort had nothing to do with a more diverse diet. The birds were worshiped. This did not mean that being a turkey in Mesoamerica was a ticket to the high life. Being sacred, they often got the chop as sacrifices.

6 Megalodon And Sipak

The gigantic teeth from the megalodon shark are impressive. These fossils date back to 23 million years ago and had an interesting impact on the Maya. A 2016 study found that the snappers could have inspired the birth of a myth. In Mesoamerican creation stories, there is a primordial sea monster called Sipak. After a hero killed Sipak, its body became the first land. Sipak iconography accurately depicts a shark, although with only one enormous tooth. It looked a lot like a megalodon fang. The study started with another shark species. Archaeologists found 47 teeth from a requiem shark at El Zotz, an ancient city in Guatemala. They were buried in a pyramid between AD 725 and AD 800, located far from the ocean. While wondering how the teeth were transported from the coast to El Zotz, another thought struck the researchers. How did the Maya explain megalodon’s teeth? Several had been found at Mayan sites as offerings. Wisely, the Maya probably knew that the teeth were ancient and physical evidence of a great shark that once lived. Their answer—Sipak—was less scientific but nevertheless something in which they believed.[5]

5 The Maya Were Not Destroyed By War

The Mayan Classic period (AD 250 to AD 900) was marked by sophistication and prosperity. However, its sudden collapse is a mystery. A plausible theory suggested that warfare exploded between the kingdoms. Indeed, entire cities and royal families were terminated after the Classic era. Historians believed that their earlier society remained stable because war avoided infrastructure and focused on capturing warriors for ransom. However, a surprising twist proved that warfare was not a major factor in the Mayan collapse.[6] Recently, scientists tested charcoal from Bahlam Jol, a Classic city in Guatemala. The city had suffered a huge fire from which it never recovered. A neighboring Mayan city produced records stating that war razed Bahlam Jol twice during the Classic era. The charcoal’s carbon dating test confirmed the time. As wholesale destruction clearly happened during the culture’s stable period, it could not have contributed to its collapse. Somehow, the Maya flourished for a long time despite the brutality. Researchers will have to look elsewhere to find the trigger that killed this culture.

4 Grocery Store Papaya’s Origins

Papaya farmers have a problem. Trees are either male, female, or hermaphrodite. Commercial growers prefer the hermaphrodite trees because they give bumper crops. But nobody knows which seeds will produce what sex. For this reason, farmers are forced to plant a ton of seeds, water them all, feed them all, and then lose up to half the trees that grow into males and females. In an effort to cut costs and find out how to grow only the desired trees, researchers looked at papaya sex chromosomes. The 2015 study found something remarkable. The hermaphrodite version was not natural. The dual-gendered papaya tree was the result of human selection that happened 4,000 years ago. This coincided with the rise of the Maya. As they were excellent farmers and the fruit is native to the region, the Maya were probably behind the cultivation of the grocery store papaya that people buy today. Interestingly, the genetic tests showed that the ancient farmers somehow created the hermaphrodite tree from the male papaya.[7]

3 Mesoamerica Was High

Mesoamericans enjoyed magic mushrooms—about 50 species of them. A 2014 study identified this psychoactive substance and more when the authors searched for early drug habits. Researchers believe that ancient civilizations needed to communicate with higher powers about the weather, warfare, disease, and fortune. Dialing a god required a mind-altering phone line. In all probability, the socially accepted highs were used for personal enjoyment as well. Apart from mushrooms, the Maya drank Balche during group ceremonies. The intoxicating drink was made from the honey of bees that fed on flowers that contained ergine. This psychedelic alkaloid caused a mild high. The Maya, Aztec, Olmec, and Zapotec shared a favorite—the peyote cactus. Laced with the alkaloid mescaline, the cactus had freaked people out with vivid hallucinations for over 5,000 years. Getting stoned from a cactus was not the weirdest option available. When not looking for psychedelic frogs, Mesoamericans also nibbled fungal stones and performed alcohol enemas.[8]

2 A Pre-Mayan Civilization Knew About Magnetism

Long before the great Mayan civilization, another flourished in Guatemala. The Monte Alto people left their footprint in the region from 500 BC to 100 BC. Like many ancient cultures, they created art. In 2019, a study examined their carvings of large heads and potbellied figures. Remarkably, some had magnetized navels, temples, and cheeks. The specific locations suggested that the artists knew about magnetism. Somehow, the Monte Alto could detect basalt that had been magnetized by lightning strikes. The stones were then carved to position the strongest magnetic points at places like the navel and face.[9] In other words, the artists not only detected magnetism in rocks but could also measure its strength. They probably invented a type of compass or sponged off a culture with the technology. One candidate is the more ancient Olmec culture. Their society’s life span overlapped with the Monte Alto people, the Olmec also carved giant heads, and at least one recovered Olmec artifact—a bar—was magnetic.

1 Acolhuas Consumed Conquistadors

When Spain colonized the Americas during the 15th and 16th centuries, their crimes against the indigenous people became famous. At least one group of conquistadors came in second against the locals. In 1520, a convoy was captured by the Acolhuas, who were allies of the Aztec. Over the course of six months, more than 100 Spanish men, women, and children were sacrificed to various gods. Their indigenous companions also met the same grisly end. When archaeologists recently visited the bloody town, they found cells and evidence that the captives were forced to listen to their companions being sacrificed in nearby rooms. Cut marks on the bones and their location also suggested that the bodies were eaten and then displayed around town.[10] The settlement’s name supported the cannibal theory. First called Zultepec, it changed to Tecoaque which means “the place where they ate them.” The convoy’s abduction was recorded by Hernan Cortes, who led the Spanish invasion of Mexico that year. His soldiers destroyed the town, but the Acolhuas knew how to survive. By the time Cortes toppled the Aztec, the Acolhuas had switched their loyalty to the conquistadors. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages