When the first explorers set out into unknown parts of the world, they had no way of being prepared for what they saw. They saw parts of the world that were completely unlike anything they had ever imagined. Then, they had to come home and try to find a way to put the things they had seen into words.

10Hanno and the Burning Jungle

Around the sixth or fifth century B.C., a Carthaginian called Hanno the Navigator set out with 30,000 people in 76 ships and sailed along the western coast of Africa. It is believed that he made it as far as modern Ghana—at the time, the furthest anyone had gone into the continent. Nobody in his world, at this time, had any idea of what to expect in West Africa, and Hanno came back with some strange reports about the people who lived there. He described people with almost mythic powers, claiming that there were a group of men living in caves who could run faster than horses. His most harrowing story, though, comes from his exploration of an island. “In the daytime we could see nothing but the forest,” Hanno reported, “but during the night we noticed many fires alight and heard the sound of flutes, the beating of cymbals and tom-toms, and the shouts of a multitude.” An oracle he had brought with him urged him to leave the island and soon as possible. When he was back on his boat and looked back at the island, it was on fire. “Large torrents of fire emptied into the sea, and the land was inaccessible because of the heat,” Hanno wrote. “Quickly and in fear, we sailed away from that place. For four days, we saw the coast by night full of flames.”

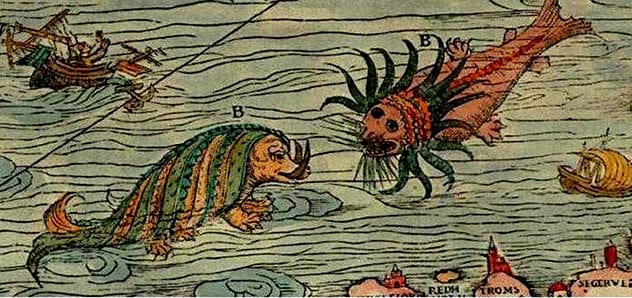

9Himilco and the Sea Monsters of Britain

While Hanno went south, down Africa, another Carthaginian, Himilco, traveled north, along the coastline of Europe and all the way up to modern England. He set up colonies along the way and opened trade routes with the people who lived there, who he called “a vigorous tribe” that were “proud spirited, energetic and skillful.” The strangest part, though, is how Himilco describes his trip. According to Himilco, Britain was under a constant fog, with shallow waters so full of seaweed that it was nearly impossible to move a ship an inch. And, he claimed, it was filled up with “numerous sea monsters.” It is not entirely clear what Himilco actually saw. He may have struggled with some animal he had never seen before and mistaken it for a monster—or he might have just lied. That is the most popular theory—that Himilco thought his discoveries in Britain were so valuable that he had to keep them secret from the world. When he came home, he told the Greeks there were killer sea monsters to keep them from exploring Britain for themselves.

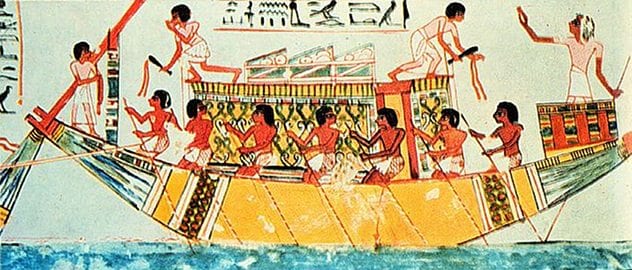

8Necho and the Trip around Africa

Sometime in the sixth century B.C., the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho outdid Hanno’s trip. He sent men out down the Red Sea and had them follow the coast of Africa, heading all the way down to the tip of South Africa, up along the west, and back through the Nile. These were the first people in all of history to circumnavigate the continent. The trip took more than two years to complete. Every autumn, the men would dock their ship wherever they were and set up farms to survive through the winter. Then, in the spring, they would head back aboard their ship and sail off again. These people traveled further south than any Egyptian had before them—which made them the first to see the sky from the southern hemisphere. When they came home, they reported that they had seen the sun shine from the north. To the people of the ancient world, though, the idea of a southern hemisphere was incomprehensible. They thought the men were delusional. Our main record of this trip comes from the Greek Herodotus, who scoffs at their claim that the sun was further north. “Some believe it,” he wrote, “but I do not.”

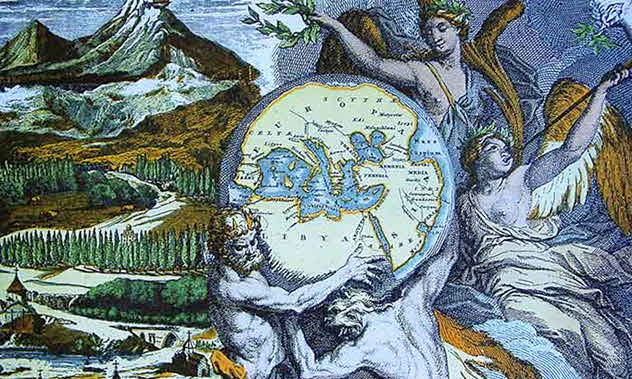

7Hecataeus’s Journey around the World

During the sixth century B.C., Hecataeus, a Greek geographer, explored as much of the world as he could. He had been to Egypt and parts of Africa, and was pretty sure that he had seen and heard enough to chart the whole world. He tried to catalog every part of the world in a book called “Journey Around the World” and even made his own world map. His map showed the world as a round disc with Greece in the center. The world, he believed, stretched no further west than the Strait of Gibraltar, no further east than the Caspian Sea, and no further south than the Red Sea. Beyond these points, there was nothing but water. Not every Greek believed him. Herodotus made fun of him, writing, “I laugh when I see that many have designed maps of the earth” that made it look “exactly circular” with “an ocean flowing round the Earth.” He was pushing his own map of the world—his, though, was pretty much the same, except that he made the earth a bit more of a misshapen blob, and he had helpfully written the word “cannibals” over northern Europe.

6Pytheas and the Frozen Ocean

Around 325 B.C., Pytheas became the first Greek to sail up the northernmost point of Britain and circle the islands. He came home and gushed about everything he had seen—and nobody believed him. Almost every record we have of Pytheas’s journey is from somebody who thinks he is lying. The Greek Strabo wrote off his entire trip as a lie, referring to him as “Pytheas, by whom many have been misled.” In particular, he mocked Pytheas for saying that Britain had a coastline 4,545 miles (7314 km) long. To Strabo, that seemed impossibly big—but, if anything, Pytheas’s measurements were too small. His reports include some descriptions that seem to suggest he reached the Arctic. He said that, north of Britain, there was a “frozen ocean” where the nights get so long that “on the winter solstice there is no day.” Some of his word choices, though, make it pretty clear why the Greeks did not believe him. North of Britain, he claimed, “there was no longer either land properly so-called, or sea, or air, but a kind of substance concreted from all these elements, resembling a sea-lungs.” Nothing, he said, could cross the sea-lungs. It sounds mythical and impossible, and kind of made-up—but he might just not have known how to describe what he was seeing. Some today think that he saw slaushed ice drifting in the sea and was just doing his best to try to explain it.

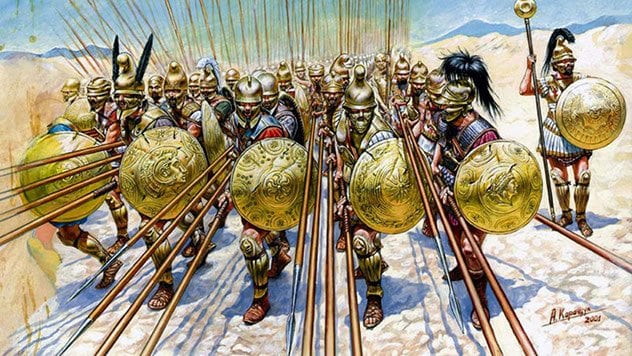

5Nearchus’s Violent Trip down the Indus River

Around the same time, Alexander the Great sent out a man named Nearchus to explore the Indus River, wanting to see if there was a safe path down the river. Nearchus was given men and ships and went out—and ended up getting into enough fights with natives to make the Spanish Conquistadors look peaceful. As soon as he started, Nearchus was stopped by a monsoon. He had to spend a month waiting for the weather to calm down. The native people, though, attacked his camp so often that he ended up having to build a fortified base out of stone just to hold them off. When he finally got going, he found another group of natives with stone age technology who tried to scare him away from landing. According to Nearchus, these people were completely covered in hair, with nails “rather like beasts’ claws.” Nearchus immediately tried to kill them all, launching missiles at them from their boat and sending an armored phalanx in to slaughter the rest. He boasted, “They, astounded at the flash of the armor, and the swiftness of the charge, and attacked by showers of arrows and missiles, half naked as they were, never stopped to resist but gave way.” He slaughtered or took captive every person he could run down, only complaining afterward that “some escaped into the hills.”

4Zhang Qian’s Journey to Mesopotamia

Around 113 B.C., the Emperor of Han sent an explorer named Zhang Qian out west, to find out who lived there, and, it seems, whether they could be added to his empire. Zhang Qian made it into part of Mesopotamia, exploring parts of Parthian Persia and the Seleucid Empire that were tightly connected to the European powers. He came back with some of the first descriptions the Chinese ever heard of these places. He was fascinated by Western coins. “They bear the face of the king,” he reported back. “When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor.” He came to the Seleucid Empire when it was collapsing after years of Civil Wars. In its weakened state, he saw it as a place “ruled by many petty chiefs,” subservient to the Parthians. On the whole, though, he was not impressed. “All these states,” he reported back to the emperor, “were militarily weak.” With a few gifts from the Han Empire, Zhang Qian believed, every one of them could be made subservient.

3The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and the First Chinese Contact

Around A.D. 60, the Greeks wrote a book called “The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.” It was their description of the Indian world—but it is particularly unique for having one of the first European descriptions of a Chinese person. The unknown writer reported seeing a tribe he called the “Sêsatai,” believed to be Chinese, journey into India. He describes them as “short in body and very flat faced” and says that they came carrying massive packs “resembling mats of green leaves.” The Sêsatai would lay out their great mats and hold a festival in India. Then, after days of celebration, these people would leave their mats behind and head back into China. This was one of the first contacts between the European world and the Chinese—although not a single word was spoken. The Greek writer simply watched them celebrate and leave, writing them off as a primitive tribe—unaware he had made contact with a massive eastern empire.

2Gan Ying’s Journey to Europe

Shortly after, in A.D. 97, the Han Empire sent an explorer named Gan Ying out west to make contact with Europe. It is likely that they had heard stories about the empires to the west, and Gan Ying was to find out if these places were real. Gan Ying made it out west to Parthia and spoke to the sailors there, but they convinced him not to go on to Europe. “The ocean is huge,” the sailors told him, warning him a trip across the sea could take up to three years. “The vast ocean urges men to think of their country, and get homesick, and some of them die.” Instead, Gan Ying got them to describe Rome in as much detail as possible. He reported back that it was a massive kingdom with five palaces in the capital. “The people of this country are all tall and honest,” he reported back. “They shave their heads, and their clothes are embroidered.” Rome, he learned, was aware of the Han Empire, and had tried to trade with them. The Parthians, though, had kept them apart to dominate Rome’s trade with the East.

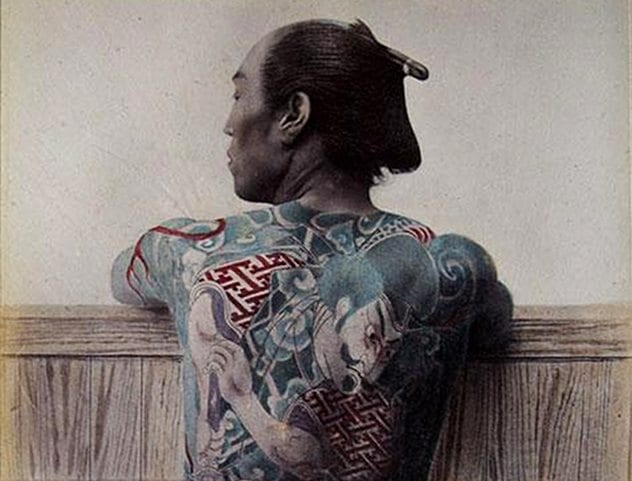

1The Wei Zhi and the Tattooed People of Japan

In A.D. 297, explorers from the Chinese Wei Kingdom traveled around the Japanese islands and reported back what they had heard. They were not the first people to make contact with Japan, but they explored the eastern sea more thoroughly than ever before. If there is any truth to what they wrote, Japan has gone through some major changes. “Men, great and small, all tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs,” the Wei explorers reported back. The people of Japan, they claimed, covered themselves in these tattoos to “keep away large fish” when they go swimming. They traveled south of Japan, too, where they claimed to have found an “island of the dwarfs where the people are three or four feet tall.” They put the Island of the Dwarfs about a year’s travel southeast of Korea, near the “Land of the Black-Teethed People” and the “Land of the Naked Men.” Read More: Wordpress