From 1478 until 1834, the Inquisition killed thousands of people in Spain and its colonies and arrested countless more. Its purpose was to root out heresy, and as we will see, it wasn’t afraid to go after children and even entire families.

10 Ines Esteban

In 1499, an unusual prophet popped up in the little Spanish town of Herrera del Duque. The soothsayer’s name was Ines Esteban, a girl of about 10 or 11 who claimed that the Messiah would come to the Earth next year. The Messiah would rescue the conversos, Jews who converted to Christianity, and take them to the Promised Land. Ines’s prophecies gave the oppressed converso community hope. She became a popular figure, followed by children and adults alike. Her followers began to practice Jewish customs again, like resting on the Sabbath and obeying Mosaic law. They eagerly awaited the Messiah’s arrival, which was scheduled for March 8, 1500. Naturally, the Inquisition was less than pleased to hear about all this.[1] A month after the Messiah failed to show up, Ines was arrested by the Inquisition and held in the city of Toledo between May and July 1500. Although Ines Esteban was still a child, the Inquisition had no mercy. The poor girl ended up being burned at the stake.

9 Diego Rodriguez Lucero

Between 1499 and 1506, Cordoba was under the thumb of Diego Rodriguez Lucero, an inquisitor nicknamed “the bringer of darkness.”[2] In one illustrative incident, Lucero sent a man named Julian Trigueros to the stake so he could take his wife. Another one of Lucero’s mistresses was taken by burning the woman’s parents and husband. Whether they were conversos or Christians, peasants or noblemen, nobody was safe from Lucero’s cruelty. He routinely used torture and threats to get confessions and never thought twice about sending somebody to burn. In June 1506 alone, Lucero handed out 100 death sentences. Eventually, everybody in Cordoba got so sick of Lucero that a marquis sent his army to attack and liberate Lucero’s prison. Lucero escaped, but the damage he caused was so scandalous that the Grand Inquisitor had him arrested in 1508. He was soon released, however, and died in Seville that same year.

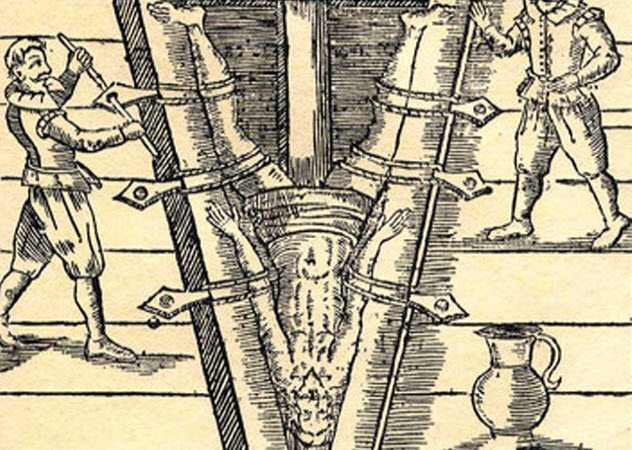

8 William Lithgow

In 1620, the Scottish traveler William Lithgow was arrested by inquisitors in the port city of Malaga. The inquisitors suspected that Lithgow was an English spy but couldn’t find anything incriminating in his possessions. They admitted to Lithgow that he was innocent, yet decided to keep him in their custody for notes he’d written criticizing Catholicism in his books. The inquisitors now accused Lithgow, a Calvinist, of being a heretic. He was tortured and starved so badly that the inquisitors were worried that he’d die. In fact, Lithgow was only kept alive by a pair of slaves, one black and the other Muslim, who sneaked him food in his cell. When he still refused to recant his religious beliefs, Lithgow was sentenced to be burned.[3] Luckily, the governor of Malaga intervened just before the innocent Scotsman was killed. He ordered Lithgow to be set free and sent back to England. It was a difficult recovery, and his left arm was permanently disabled from the Inquisition’s torture. But Lithgow survived and later wrote a book about his travels.

7 Joseph Perez

The Spanish Inquisition was mostly used to stamp out heresy, but it sometimes prosecuted people for other crimes, too. In the Kingdom of Aragon, for example, the Inquisition was allowed to handle sodomy cases. As in the rest of Spain where sodomy was handled by secular courts, the Inquisition originally treated it as a capital offense. In 1633, the Aragonese Inquisition stopped giving out the death penalty for sodomy but only after they had conducted nearly 1,000 sodomy trials. One of the many men executed in these trials was Joseph Perez, a university professor who was taken into custody in 1613 for allegedly making passes at two of his students.[4] While waiting in prison, Perez apparently grew mad, so the Inquisition provided him with a doctor. At first, Perez was only going to be fined and banished. But then he met with his attorney, telling the man that the accusations against him were true and that he’d been having sex with his doctor in jail. This was a terrible idea on Perez’s part. The attorney was technically his letrado, an attorney hired by the Inquisition. Needless to say, the letrado tattled, and Perez and his doctor were both sentenced to death.

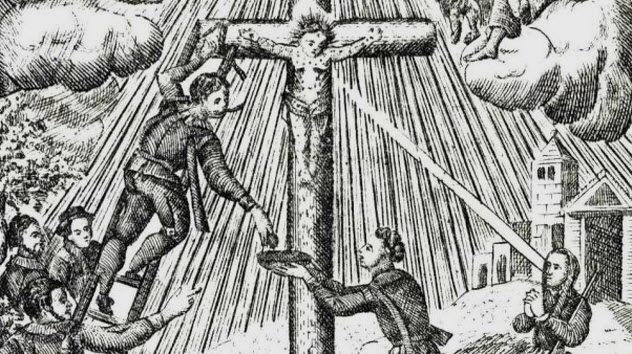

6 Pedro de Arbues

The Inquisition was set up in the Kingdom of Aragon in 1484, but the wealthy converso community figured they would put up a fight with it. When the inquisitor Gaspar Juglar suddenly died, it was rumored that the conversos had poisoned him. The following year, some conversos organized a plot to kill another inquisitor, Pedro de Arbues.[5] In September 1485, Arbues died after being attacked by a group of assassins in a cathedral. The murder sparked public outrage, and the Inquisition quickly struck back in revenge. They jailed hundreds of people and uncovered and executed most of the chief conspirators. One man was beheaded, with his head publicly displayed on a pole. Others had their hands cut off before being decapitated and quartered. Ironically, before Arbues’s murder, a lot of people in Aragon hated the Inquisition. The conversos’ plot was meant to weaken the then-new institution, but all the assassination really did was warm people up to it.

5 Ana de Castro

In 1707, the beautiful Ana de Castro left Spain with her husband and moved to Peru. At first, things were hard for Castro in her new home. But thanks to her good looks and a marriage to a new husband, Castro became very rich and popular in Lima. Castro’s beauty attracted a lot of lovers, and in 1726, one jealous man set up a scheme to ruin her. He had a maid hide a crucifix in Castro’s bed, and then he made up a lie to the Inquisition that Castro had whipped it. Sure enough, the Inquisition found the crucifix in her bed and arrested her. After being tossed into jail, Castro had her fortune seized by the Church. She was held there for over 10 years and tortured three times while she waited for the outcome of her trial. Castro was accused of being a Judaizer, a converso who practiced Judaism in secret. Though she told the authorities that she’d repent, an action which legally should have spared her life, Castro was executed anyway in December 1736.[6]

4 The Bohorques Sisters

Maria de Bohorques was a bright young woman in Seville who spoke Greek and Latin and read Lutheran books. She was very interested in Lutheranism, and when the Inquisition interrogated her, she insisted that it had some truth to it. Before Maria was executed for heresy, she told her torturers that her sister Jane had no problem with her ideas. Even though she was six months pregnant at the time, Jane was thrown in jail with no proof but her sister’s confession. She gave birth while in prison and only got to be with her baby for eight days before the child was taken away from her. Afterward, Jane was bound with cords and tortured until she bled from the mouth. A few days after her torture session, Jane died in prison from the abuse. On the same day, after her death, the Inquisition declared that she was innocent.[7]

3 The Carabajal Family

In 1580, the Portuguese-born Luis de Carabajal y Cueva arrived with hundreds of settlers in Mexico to create a colony for the Spanish. His sister, Francisca Nunez de Carabajal, along with her husband and eight of their children, also came along. Luis colonized and governed the modern-day state of Nuevo Leon, but Francisca and her family later relocated to Mexico City. Life was great in Mexico City until 1590 when the Inquisition suddenly arrested Francisca and her family.[8] The Carabajals, a family of conversos, were accused of practicing Judaism. Sadly, under torture, the family fell apart. Francisca confessed that her husband and children were guilty, while her son Luis Jr. testified against his mother and siblings. In December 1596, Francisca and five of her children were burned at the stake. Her husband died before the execution, and a son named Baltasar escaped the Inquisition by fleeing the city. Another daughter, Mariana, was executed six years later. Only Francisca’s two youngest children, Anica and Miguel, were ultimately spared.

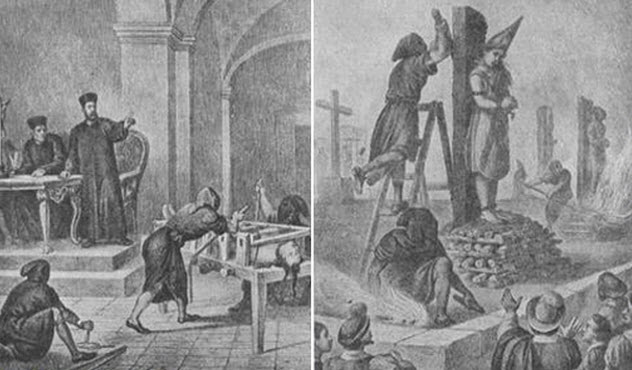

2 The Holy Child Of La Guardia

In summer 1490, two Jews and six conversos were arrested by the Inquisition for allegedly killing a Christian boy near the town of La Guardia. The charge was ridiculous, but one of the men, Juce Franco, confessed that it was true. He claimed that he and his companions had crucified the boy in a cave, removed his heart, and then drained the blood out of him. The other prisoners gave conflicting accounts about the story. None of them could agree on the date, the name of the boy, or even where they got their victim. The evidence was also nonexistent. Nobody had been reported missing in La Guardia, and the spot where the boy was supposedly buried failed to turn up a body. Instead of concluding that their prisoners were innocent, the Inquisition believed that they were a bunch of liars and sent them to the stake. Their fake victim, meanwhile, became a folk saint known as The Holy Child of La Guardia. Amazingly, some people in La Guardia continue to believe in and honor the boy’s death in the 21st century.[9]

1 Cayetano Ripoll

By the 18th century, the Spanish Inquisition had fallen into decline. Spain’s new Bourbon dynasty centralized and reformed the country, while the skepticism of the Enlightenment hurt the Inquisition’s credibility. During the whole century, only four Inquisition trials resulted in executions. The last person sentenced to death by the Inquisition was a deist named Cayetano Ripoll. A teacher, he was essentially arrested for neglecting his students’ religious education. In July 1826, after being held in jail for two years, Ripoll was hanged for heresy. After his death, Ripoll’s body was put into a barrel that had flames painted on it, which was meant to symbolize burning.[10] Ripoll’s execution shocked Spain and drew criticism from across Europe. At this point, the Inquisition had been abolished and revived twice, once in 1808 and again in 1820. Finally, in 1834, the queen Maria Christina abolished the bloody institution for good. Tristan Shaw runs a blog called Bizarre and Grotesque, where he writes about folklore, paranormal phenomena, and unsolved crime.