10 The Lewis Chessmen

In 1831, chess pieces were discovered in a sand dune on the Isle of Lewis. They were carved from walrus ivory and whale teeth into small statues depicting royalty, bishops, mounted knights, warders, and pawns. Beautifully detailed and measuring 6–10 centimeters (2–4 in) in height, the four distinct chess sets were incomplete but had 93 game pieces in all. Even today, nobody knows where they came from or who made them. While some people believe the origins of these sets are Irish, Scottish, or English, it’s most likely that Scandinavian hands formed the iconic pieces. The figures appear to have been heavily influenced by Norse mythology. The age of the artifacts dates from the late 12th and early 13th centuries, a time when Norway owned the beach where they were found. Despite being over eight centuries old, the condition of these chess sets is pristine, almost like they were never used. Another theory is that the chessmen aren’t chess pieces at all but rather belong to a hnefatafl set, a game similar to chess. Whatever their true history, the Lewis chessmen remain one of Scotland’s most famous ancient finds and the largest known group of objects to survive from that era.

9 The Loch Village

Originally, it was believed that Wigtownshire in southern Scotland was first inhabited by people who founded a church there in AD 397. However, in 2013, archaeologists were excavating a single crannog (an ancient loch home) when they discovered the only known loch village in Scotland. This incredibly well-preserved Iron Age settlement has at least seven roundhouses dating to the fifth century BC. So by the time the church was built in AD 397, this village was already a sophisticated farming community thriving around a small loch. The loch no longer exists, but the village remains in good condition, including some of the timber structures. In one of the most unexpected finds, the roundhouses were constructed directly over the fen peat without artificial foundations. The site is the only one of its kind in Scotland, and it changes the traditional history of the southern part of the country.

8 New Language

Once mistaken for rock art, an unknown written language dating back to the Iron Age was identified in 2013 as belonging to an ancient Scottish people known as “the Picts.” They consisted of different Celtic tribes and left a legacy of hundreds of rocks bearing mysterious inscriptions. The “Pictish Stones” show highly artistic renderings of unknown symbols, although some are recognizable as animals, soldiers, weapons, and battle scenes. Even so, researchers have only established that the carvings represent a lost language of the tribes that once occupied eastern and northern Scotland. They don’t know how many of the symbols actually represent the Pict language and how many are just imagery. If experts ever crack the code—something that seems unlikely unless the Pict equivalent of a Rosetta stone is found—then it could reveal what life was really like for Scotland’s ancient Celtic people.

7 The Islay Artifacts

When a gamekeeper released pigs on the Isle of Islay, he expected the porkers to graze on bracken. Instead, the animals made a discovery that changed the known history of the island. While rooting about, the pigs unearthed the tools of a hunter-gatherer society on the east coast that turned out to be the earliest evidence of human habitation. Archaeologists were amazed by the discovery. The artifacts included animal remains, crystal quartz tools, spatula-type objects, other hunting tools, and a fireplace. But the wow factor came when these artifacts were found to be around 12,000 years old, placing people on the Isle of Islay nearly 3,000 years earlier than originally believed. Upon closer inspection of the workmanship of the artifacts, researchers believe that the owners originally came from central Europe, specifically from the Ahrensburgian and Hamburgian cultures. During that time, Britain was connected to Europe, which would have enabled these reindeer hunters to come to the Isle of Islay.

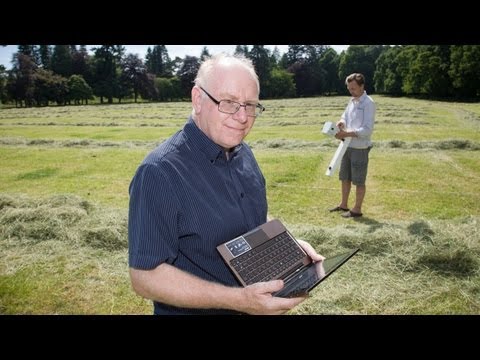

6 World’s Oldest Calendar

In 2013, researchers discovered the world’s oldest known lunar calendar in a Scottish field. During a survey project recording new archaeological sites, the unusual alignment was first spotted from the air at Warren Field near Crathes Castle. Following up with a two-year excavation, experts uncovered 12 pits that appear to have been constructed to follow the Moon’s phases, track lunar months, and line up with the midwinter sunrise. The ancient calendar most likely aided Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in tracking time and following the seasons more accurately. Incredibly, the time-telling field was created almost 5,000 years before the first calendars appeared in the Near East. Approximately 10,000 years old, the pits are arrayed in an uneven curve and may each have held a wooden post at one time. This unique calendar may also be one of the first steps that humans took toward formally attempting to understand the concept and passage of time.

5 St. Ninian’s Treasure

In 1958, a schoolboy named Douglas Coutts made an extraordinary find. While on St. Ninian’s Isle, Shetland, Coutts was helping with the excavation of a site where a medieval church once stood when he found a wooden box beneath a flat stone with a cross. Inside was a valuable trove of silver which became known as “St. Ninian’s Treasure.” We don’t know who originally owned the treasure or how it came to be buried beneath the stone. The most credible theory suggests that an aristocratic family gathered these heirlooms over several generations. Beautifully decorated, the 28 pieces include quality jewelry, bowls, cutlery, and ornamental pieces that may have been removed from weaponry (most likely swords). The only object that seems out of place in the collection is the partial jawbone of a porpoise. Some researchers believe that the items were buried around AD 750–825 for safekeeping, a time period that coincides with the first Viking raids on Scotland. So far, the collection is the only example of such superb metalcraft to survive from that era.

4 The Ballachulish Figure

The Ballachulish figure may not be the most beautiful girl in the world, but she’s been admired by millions. When this wooden figure of a young woman was discovered by builders working near Loch Leven, it became the most ancient human figure ever found in Scotland. Carved from alderwood, the nude figure was determined to be over 2,500 years old. She looks like a simple piece of plank that’s the height of a girl. While her creators and purpose remain a mystery, it’s possible that she was a fertility or protection goddess. Her location lends some weight to the latter theory. During her heyday in Ballachulish, she probably stood on a raised beach as suggested by the pebbles stuck in the lower part of the carving. As her quartzite eyes gazed over the dangerous straits linking the sea and Loch Leven, the sight of such a protective deity may have given hope to ancient travelers. The fertility goddess aspect is linked to what she’s holding—something resembling male genitals. However, the statue’s details are too damaged to be sure. When found in 1880, the fateful choice to dry out the waterlogged artifact caused it to warp, break, and lose much of its detail. Prehistoric wooden figures exist in other countries such as Britain and Ireland, but the Ballachulish figure remains unique to Scotland.

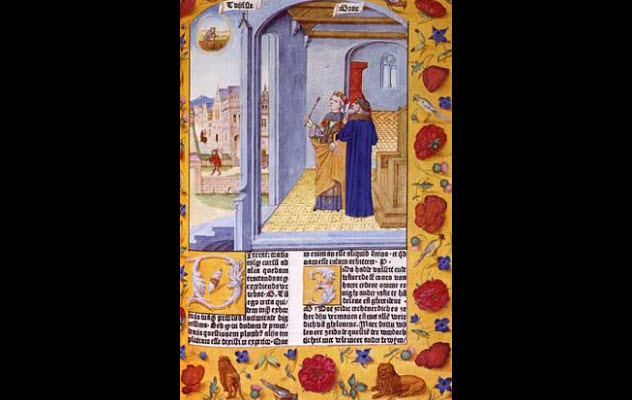

3 The Boethius Manuscript

Boethius was a Roman statesman who wrote one of the most powerful documents of medieval Europe, second only to the Bible. Called The Consolation of Philosophy, it’s believed to have been penned in AD 524 when Boethius was wrongfully imprisoned and facing execution. In 2015, a 12th-century copy came to the attention of Dr. Kylie Murray from Oxford while she was doing some research in the University of Glasgow’s Special Collections. The manuscript’s existence was nothing new, but scholars had always believed it was of English origin. Murray’s study dropped a bombshell. The Boethius manuscript had no similarities to any English books belonging to that period but instead had solid connections to Scotland’s King David I. An inscription commonly found on the king’s documents was discovered in the Glasgow manuscript. The Boethius manuscript also has unique, elaborate illustrations that closely resemble those of the finely decorated Kelso Charter, a work of the monks at Kelso Abbey from 1159. Kelso was also David’s chosen monastery to write his documents. This means that the Boethius copy in Glasgow is now the oldest surviving nonbiblical manuscript from Scotland. Historically, this discovery has immense value because it points to a lost literary culture that once flourished in the country centuries earlier than previously believed.

2 Skara Brae

In 1850, a storm removed enough sand from the coastline of Scotland’s Orkney Island to reveal a lost prehistoric village that had been hidden under the dunes for 5,000 years. Skara Brae is so well-preserved that it appears to be frozen in time. Visitors can still see the innovative stone furniture in the homes, looking like the villagers just left even though it’s several millennia old. Occupied for about six centuries, the village consists of about 10 houses connected by alleyways and sheltered passages that made neighborly visits easy, even in winter. Stone was used for nearly everything, from constructing insulated walls to beds, shelves, and even sophisticated tools. But Skara Brae is a place of mystery. One of the houses is different from the rest. It has no furniture, and it’s not linked by a passageway to the other houses. It’s pockmarked with nooks in the wall that look like post office boxes. It’s also one of only two buildings decorated with wall carvings. According to one theory, this building was the village workshop. The only other decorated house in the village is the strangest one. It has a bull’s skull sitting on one of the beds and two women buried inside. Skara Brae was once miles away from the ocean, but Orkney’s coast has crept so close that a seawall now protects the village.

1 The Ness Of Brodgar

The Ness of Brodgar is an ancient complex comparable to the greatest archaeological sites such as the acropolis in Athens. But the Scottish ruins are 2,500 years older. Around 3200 BC, the ancient Orkney inhabitants used thousands of tons of sandstone to build a site that was a masterpiece of workmanship and grandeur. Among the many structures was one of the greatest roofed buildings of prehistoric northern Europe, running over 25 meters (80 ft) long and 20 meters (60 ft) wide. The ruins also yielded 650 pieces of Neolithic art, the largest collection in the UK as of late 2015. The so-called “temple complex” is surrounded by other Stone Age monuments. In the same area are the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness, both stone circles, and the 4,500-year-old chambered tomb called Maeshowe. Maeshowe’s entrance marks the winter solstice and aligns with the entrance to the new temple. Archaeologists suspect that the four monuments share a unified history and a purpose not yet understood. After a millennium of use, the temple complex was abandoned in a ceremony that saw the killing of over 400 cattle. But only their shinbones, arranged around the temple, were ever found. Untouched deer carcasses were piled on top of the bovine bones. A single cow’s head and an engraved stone were placed in the middle of the building. Then the rest of the complex was deliberately destroyed and buried. Why it was demolished may never be known. According to some theories, changes in society brought about by climate change or the arrival of bronze may have contributed to the inhabitants’ desire to erase all evidence of their earlier belief systems. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages