You’ll notice some common themes throughout the list, as many of these controversies have arisen because of modern industrial farming practices, and the two sides of an issue are often split based on whether we see cattle more as commodities or fellow living creatures. In most cases, I aim not to take sides but simply to present the issues. (For the record, I’m no vegan.) Decide for yourselves, and share your thoughts on these and other contentious cattle-related issues in the comments.

The wise man said, “This is a male camel. As it gets older it will get unruly. You should castrate the beast to save you trouble.” The young man asked, “How do I accomplish this, O wise one?” The wise man replied, “You take two large stones, hold one in each hand, place the testicles between them, and bring the stones sharply together.” “But surely this will cause severe pain,” said the astonished young man. “Not if you are careful to keep your thumbs out of the way.” I’m not sure of the origin of this old joke, but it’s been circulating for decades and provides a good reminder of how we view and value our livestock. Animal welfare advocates argue that castrating bulls is unnecessary and cruel, saying that bulls actually bulk up better and produce more meat than steers, their castrated counterparts. Not only is the process of castration painful, but it also puts the animal at risk of infection. However, those in favor of castration say it reduces aggression in livestock and that people prefer the taste of beef from steers, which is usually more marbled and less tough, making it more marketable. Aggressive bulls are also more likely to damage equipment and injure other cattle or their human handlers. Even among castration supporters, a debate of when and how to castrate rages. Calves heal better after surgical castration than older animals, but surgical castration on calves is usually done without anesthetic. Other methods involve cutting off circulation to the genitals using rubber rings; eventually, the testicles fall off. But does this cause the animal more pain than simply cutting the gonads off?

Animal science professor Temple Grandin has devoted her life to creating more humane livestock-handling systems in slaughterhouses. Her autism, which allows her to see the world through the eyes of cows and other animals, informs her many innovations that make an animal’s final moments as calm and peaceful as possible. In line with her recommendations, most cattle today are slaughtered using a captive bolt stunning gun (think No Country for Old Men), which, when used correctly, instantly kills the animal. However, Jewish and Muslim communities don’t consider this type of slaughter to be in keeping with their religious dietary laws, which require that cattle be slaughtered with a single, swift cut to the throat that severs the jugular veins and carotid arteries but leaves the spinal chord intact. Causing minimal suffering is one of the aims of such ritual slaughter, but it’s not always done right; earlier this year the government of Australia faced pressure to end live cattle exports to Indonesia, where videos surfaced of inhumane slaughtering practices.

Some people object to the idea of eating a baby animal, but veal is nothing more than a byproduct of dairy farming: in order to produce milk, cows have to give birth, and because of worldwide milk demand, the cows produce more babies than we could possibly support as fully grown cattle. So if you’re a vegetarian for ethical reasons but you consume dairy derived from factory farming, you’re actually inadvertently fueling the veal industry – especially if you eat cheese, which requires not only milk but also the rennet from a calf’s stomach. Others find cruel the practice of depriving a veal calf of both its mother’s milk (so that we can drink it) and of solid cattle feed (so that its flesh will stay pale); instead these calves are fed whey formula from birth. Eating free-raised veal, where a calf has unlimited access to its mother’s milk as well as pasture, is probably as ethical as you can get (see also #1) while still eating beef.

Farmers in North America are permitted to give cattle hormones to boost their growth and productivity, although synthetic hormones aren’t allowed in Canada. Growth-promoting hormones are banned altogether in Europe. The major concern is that humans can absorb these hormones when they eat beef or consume dairy products, potentially leading to health problems such as cancer. The hormones might also leach out of the cattle’s waste and into the environment, where their effects on wildlife can be potentially devastating. The North American cattle industry defends its stance, citing research that proves hormonal growth promoters don’t pose a threat to human health and saying that not using the hormones would vastly increase beef prices for consumers. A related debate concerns the use of antibiotics, and critics blame factory farming. Antibiotics are frequently required when animals are kept in close quarters and share the same feed. When they have access to pasture, disease transmission is drastically reduced. Clinical antibiotic administration—when an animal actually becomes ill—is not the major point of contention; rather, it’s the sweeping administration of antibiotics as a preventive measure that some believe to be a major contributor to global antibiotic resistance.

Anyone who grew up on a dairy farm will tell you that milk tastes best straight from the cow. Raw milk proponents would agree, and they’re pushing governments to allow the sale of unpasteurized milk, which is illegal in many jurisdictions. They argue that pasteurization alters the nutrient balance in milk, destroying beneficial bacteria, enzymes, and milk’s antimicrobial properties, as well as altering its natural sweetness. Many raw milk advocates believe that pasteurization is necessary only because of factory farming, where milk from all of the animals, some of which may be ill, are mixed together in a big vat, inevitably leading to contamination of the whole batch; they are adamant that if a cow isn’t diseased, and if she has access to pasture and produces milk free of blood or coagulation, the milk is perfectly safe to drink. Proponents of pasteurization would disagree; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports that raw milk is responsible for three times the hospitalizations compared with other food-borne illnesses. Milk can be contaminated at any point between milking and consumption, including transport and bottling, and could contain E. coli, salmonella or listeria. In Canada, selling raw milk and raw milk products (aged cheese is an exception) is still illegal. Some raw milk fans have gotten around legal restrictions by participating in cow-sharing agreements – owners can legally drink raw milk from their own cows. And twenty-eight U.S. states, including California, Washington and Maine currently allow the sale of inspected and certified raw milk in grocery stores.

One of the major reasons ruminants like cattle, sheep and goats have historically been so important to humans is that they’re able to turn something we can’t digest (the cellulose in grass) into something that we can (milk or beef). So advocates of grass-fed cattle argue that feeding them something that we can already readily digest – grain – is a waste of food. Grass-fed cattle aren’t as productive as grain-fed animals, however, and the latter have higher fat content and better marbling, which makes their beef much more marketable. This debate is, once again, centered on the issue of industrial farming, since grass-fed cattle are typically allowed access to pasture, a practice that requires more land and labour resources, whereas grain-fed cattle are usually penned within large factory farms. Critics of grain feeding insist that cattle’s natural diet consists of grasses, not grains, and that their digestive systems simply can’t handle grains very well, which leads to illnesses that necessitate antibiotics (see #7).

So keeping cows penned in and grain-fed may be good for preserving our landscape while creating more marketable beef. But is there a way to accommodate grazing while encouraging plant growth? Zimbabwean farmer and biologist Allan Savory thinks so. He noticed that in the wild, grazing animals stay in tight groups to protect themselves from predators. They fertilize that small area with their dung, then move on to another small patch of plants, allowing the first patch time to regenerate and grow. By carefully emulating this pattern (rather than letting cattle disperse over a wide range), using a framework that Savory has dubbed “holistic management,” ranchers can actually promote the growth of native plants, leading to increased biodiversity and sustainability.

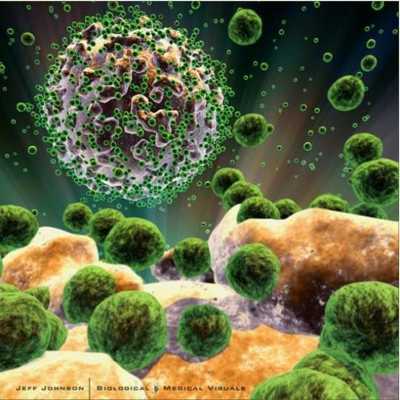

BSE, or mad cow disease, is a degeneration of the brain caused by a pathogenic protein, or prion. The infected animal develops holes in its brain that cause problems with coordination, excessive aggression and, ultimately, death. Most researchers believe the disease originated because cattle – vegetarians by nature – were fed meat and bone meal as a protein supplement. The meal was derived from dead cattle and may have been contaminated at a slaughterhouse or processing plant with the prion that causes scrapie, a similar disease in sheep. BSE has been linked to what’s known as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob (vCJD) disease in humans, a terrifying neurological disorder that begins with dementia, memory loss, personality changes and hallucinations, progressing to loss of balance and coordination and ending, invariably, with death. After onset, patients typically have only months to live. The practice of feeding an animal to a vegetarian is offensive enough to many people, but the fact that cattle were eating dead cattle meant that humans were essentially forcing them to be cannibals. A ten-year ban on beef exports from Britain, where occurrences of BSE and vCJD were most common, and regulation changes to cattle feed ensued after the outbreak in the mid-1990s. However, to this day, cattle are still given feed derived from the remains of animals – just not those of ruminants. Since vCJD can have a long incubation period of several years and possibly decades, whether this restriction is strict enough may yet have to be evaluated.

In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released the results of a risk-assessment study that concluded that cloned animals are just as safe for the food supply as normal animals. Supporters of cloning see it as nothing more than an extension of existing cattle husbandry practices, including selective breeding and artificial insemination. If you have an animal with very desirable traits – like disease resistance, high milk production, and the like – why wouldn’t you want genetically identical copies rather than roll the dice with typical sexual reproduction? Opponents decry the practice as highly unnatural. When the very first cloning experiments were carried out in the 1980s, the results were unpredictable – disabled or severely ill freak cattle were not uncommon. Although cloning techniques have become more reliable, the risk of malformed offspring – not to mention the slippery-slope argument of applying cloning practices to humans – raises ethical questions. Moreover, having a massive population of genetically identical animals makes them – and those that depend upon them – extremely vulnerable to factors like disease that could wipe out the entire herd. It is, in essence, mono culturing taken to extremes. What bothers many opponents in particular is that cloned beef doesn’t have to be specially labelled, and the consequences of cloning and eating cloned beef may not become obvious for many years.

There’s no question that burning fossil fuels emits greenhouse gases, but some climate change experts say that we should direct at least as much of our attention to our livestock as culprits of climate change. Cattle, like all ruminants, belch out methane, a greenhouse gas that’s more than twenty times more potent than carbon dioxide. What’s more, in many parts of the world cattle ranching goes hand in hand with deforestation (see #4), the destruction of one of nature’s most efficient carbon sinks. From a climate-change perspective, eating veal is actually a bit better than eating full-grown cattle, since the calves are not digesting cellulose and so produce less methane, but beef in general has twice the carbon footprint of an equivalent amount of pork. And eating cheese is just as bad as eating beef, according to Mike Berners-Lee’s How Bad Are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything, since a huge volume of milk is needed to produce a small quantity of cheese. Berners-Lee suggests that to mitigate the climate impact of your cheese, you should go for soft cheeses, which are less milk-intensive than hard cheeses, and not to waste cheese if you’ve got it; mould on hard cheeses is no reason to discard the whole brick. Of course, the most climate-friendly solution is to stop eating beef (and goat and lamb) altogether, but as the world’s developing economies grow, global meat consumption is probably just going to keep climbing.