Top 10 Disastrous Mistakes Performed During Surgery

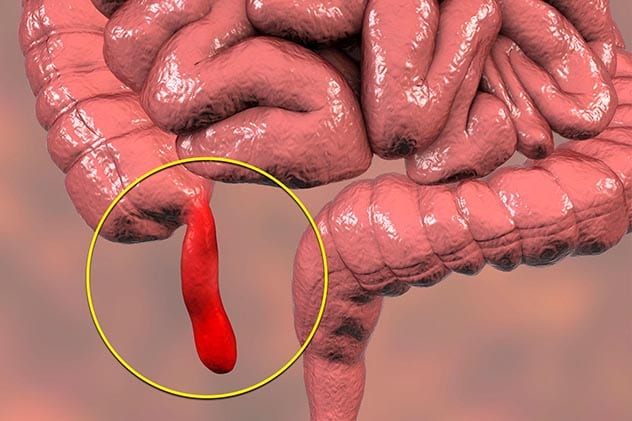

10 First Appendectomy: Removal of an 11-Year-Old Boy’s Appendix in 1735

Appendicitis, a condition where the appendix becomes swollen, inflamed, and filled with pus is a common condition effecting 8% of people at some point in their lives. If left untreated, the Appendix will burst, spilling bacteria and debris into the abdominal cavity—likely proving fatal unless treatment is performed immediately. This condition has been well documented throughout history. As early as A.D. 130 the anatomical writings of Galen described the condition and it continued to be discussed off and on by medical practitioners for millennia. Strangely though, the cause of this condition was unknown. The appendix itself was only discovered in the late 1400s and its link to the pains written about ever since the time of Galen were only confirmed by German surgeon Lorenz Heister in 1711. In all of that time, 8% of every human that ever existed suffered and likely died from the condition without ever knowing why. But knowing why wasn’t as critical as finding a solution. Decades after the appendix was discovered, the very first appendectomy was performed on an 11-year-old-boy in 1735 by Doctor Claudius Amyand. In this case, the boy’s appendix had been punctured by a pin that he had swallowed. The surgery alone was a landmark case, but the boy also had a rare condition—a type of inguinal hernia (a hernia where a piece of intestines pokes through a weak portion of abdominal muscles) that came to be named after Amyand himself. In one fell swoop the first appendectomy was performed and the first Amyand hernia discovered. It would be another 24 years until an appendectomy was finally used as a treatment for appendicitis. Today almost 300k appendectomies are performed every year just in the United States, saving that 8% of the population from immense pain and death.[1]

9 First Brain Surgery: Trepanation Performed On Our Distant Ancestors

Surrounding our brain is a thin layer of protective tissue called meninges, which contains an abundance of blood vessels. Sometimes when dealt head trauma, the meninges can tear and bleed. This blood is then trapped between our brain and our skull and as the bleed continues, pressure builds and pushes dangerously against our brain. This is a condition known as subdural hematoma. If allowed to continue building, this pressure will eventually cause damage to the brain and could even led to death. To treat this condition, a small hole can be drilled into the skull that allows the blood to be released—like a pressure valve. These are called burr holes and the procedure is called trepanation. Though this may sound like a very modern solution, this form of brain surgery has been practiced for 5,000 years. In fact, 5-10% of all skulls found from the Neolithic period (which lasted from about 12,000 years ago to 4,000 years ago approximately) have burr holes. Even thousands of years ago, this method was used to treat subdural hematomas in an age long before modern painkillers of anesthetics. But the procedure wasn’t always a treatment. Twelve human skulls were all found within a 31 mile radius in southern Russia. All 12 dated back to the copper era and all 12 had burr holes located in the exact same place on the skull—the obelion, located in the back top of the skull, roughly where we might set a ponytail. None of these skulls showed any signs of trauma, suggesting they were all healthy at the time of the operation. Elena Batieva, an anthropologist from the Southern Federal University in Rostov-on-Don concluded that these 12 individuals were perfectly healthy and needed no trepanation. Instead she suggests that their skulls were ritually drilled. This is particularly fascinating, because the obelion is an especially dangerous place to place a burr hole. Indeed, several of the skulls showed no signs of healing which is proof their owners died from the trepanation. The exact nature of their ritual and what they hoped to gain from it are not written in their bones. We can only guess at their motivations.[2]

8 First Biopsy: A Hollow Needle in A.D. 1000

Though the term biopsy (retrieving a sample of tissue for examination as a way of diagnosing a patient, most commonly with a hollow needle to reach deep tissue) was first coined in 1879 by Ernest Besnier, but the practice itself long predates the vocabulary. The earliest biopsy was performed by court physician Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi (also known as Albucasis) who lived between A.D. 936-1013 He used a long needle to reach and examine tissue from the thyroid gland. Ultimately this method allowed him to diagnose what he called “Elephant of the throat”, with a procedure much like an FNA (fine needle aspiration) that’s used today. Albucasis’ writings also included detailed descriptions of his instruments, showing that he used the first hollow needles described in medicine—The precursors to the tools we use today for everything from biopsies and injections to drawing blood.[3]

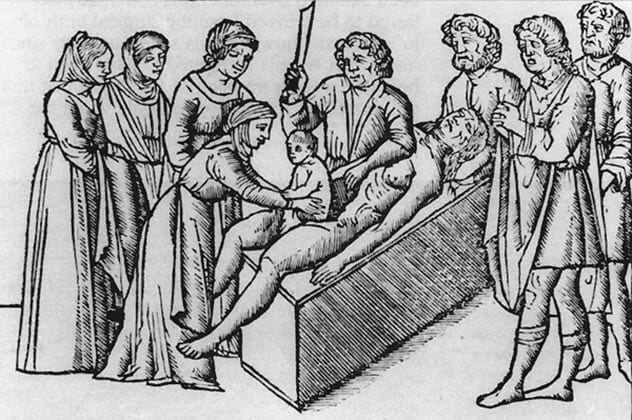

7 First Successful Cesarean: Mother and Child Saved In 1794

Originally a cesarean delivery of a baby was an operation only performed when a mother was either dead or dying. The mother would already be considered a lost cause and the cesarean would all but guarantee her demise, but it could still save her baby. In this context there have been many successful cesarean operations since ancient times. Even in mythology it was commonplace. In Greek Mythology the demigod Asclepius was born when his father Apollo removed him from his dead mother’s womb. But a cesarean section where BOTH the child and mother survive was the holy grail of the operation. Attempts were made even in the middle ages, even supposedly successful ones (but the validity of their claims is in question). But the first unquestionably successful operation took place in America in 1794. Elizabeth Bennett was suffering through a difficult childbirth and, fearing for her child’s life, requested that her physicians perform a Cesarean and save her baby. The physicians refused on moral grounds, a cesarean would surely kill her. Instead, her husband Jessie Bennett, also a doctor by trade, stepped in to save his own child. Against all odds, he successfully saved both his child and wife—A first for history. Today, one third of all births in the United States are done by cesarean section.[4]

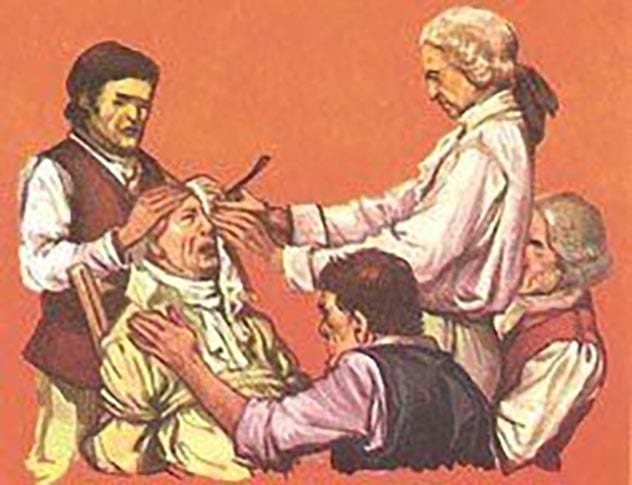

6 First Cataract Surgery: Ancient “Couching” Technique

Cataracts are a build up of protein within the lens of the eye that creates an opaque, foggy layer that blocks light and blurs eyesight. Most commonly cataracts develop because of the aging process and have plagued humans all throughout our history. One of the earliest surviving records of the condition is an Egyptian statue depicting a priest reader named Ka-aper from 2457-2467 B.C. In this statue, the priest is depicted with one heavily clouded eye. For just as long as we have suffered from them, we have also striven to cure them. In a tomb of a Pharaoh’s surgeon, built in 2630 B.C. were found a very particular sort of instrument—a copper needle or lancet. These were used to reach to the cataract within the eye and forcible dislodge them, sinking them deeper into the vitreous body of the eye, between the lens and the retina. This was deemed, “couching”. Though not removed, the operation would usually result in clearer vision for the patient, who may no longer be gazing directly through the concentrated protein. It was this procedure that was likely discussed in the famous Code of Hammurabi, an ancient king who ruled starting in 1750 B.C. One of his laws stated, in part, “If a doctor operates…on the eye of a patrician who loses his eye in consequence, his hands shall be cut off.” This operation continued to be commonplace until 1748 when a French doctor named Daviel performed the first cataract extraction surgery.[5] 10 People Who Woke Up During Surgery

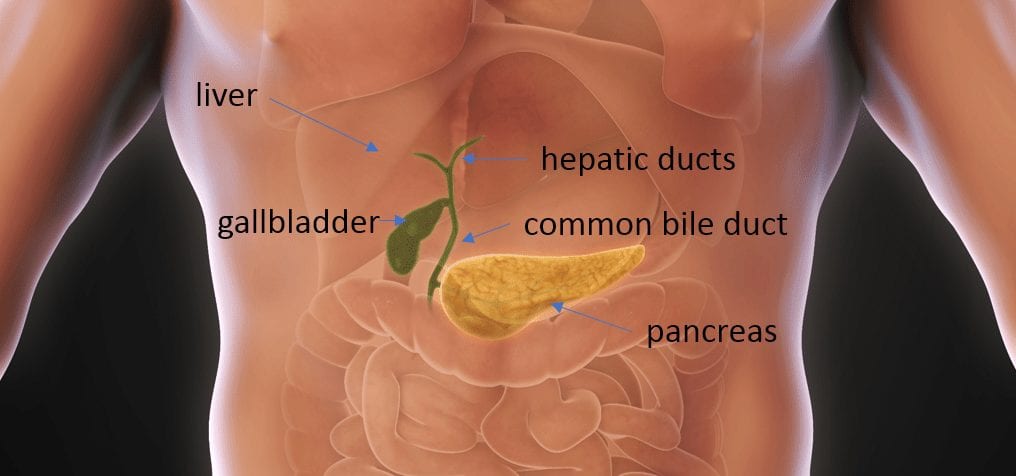

5 First Cholecystectomy: Removal of the Gallbladder in 1882

The Gallbladder is a small pouch shaped organ just below the liver responsible for storing and dispensing bile produced in the liver after a meal to help digest fat. It can develop problems such as gallstones, infections, or even cancer on rare occasions. It was these sort of issues that troubled the patients of Carl Johann August Langenbuch, a 27 year old German physician in Berlin in the 1880s. To help relieve his patient’s ailments he would perform the common treatment of the day and surgically open their abdomen , cut into the gallbladder, and clear out its contents—be they gallstones or infections. This was a painful process and only offered temporary relief. This frustrated Mr. Langenbuch. So he decided on a new approach. One discussed among physicians, but its outcome was uncertain. He wanted to completely remove the gallbladder, but no one knew exactly what would happen. Some were worried the effects could even amount to death. He practiced the operation first on a cadaver and finally in 1882 removed the gallbladder from a living patient who had suffered from gallstones for 17 years. The patient was cured overnight with extremely limited side effects. By 1897 over 100 Cholecystectomy operations had been performed and today it is the second most commonly performed operative procedure.[6]

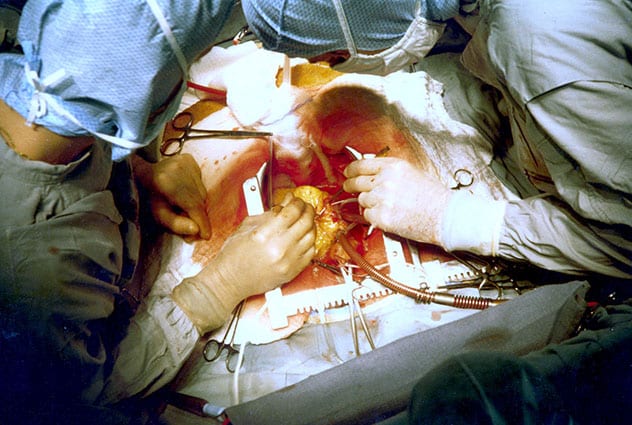

4 First Coronary Artery Bypass Graft: Performed in 1960

A Coronary Artery Bypass Graft surgery (CABG) is a procedure to circumnavigate a blocked area of blood vessels in the heart with a new section of vessel taken from elsewhere in the body. The story of the CABG is one of small evolutions. As early as 1910 the ground work was being laid by a doctor named Alexis Carrel who mused about operating on the coronary circulation and then successfully did so on dogs. In 1935 a Claude Beck worked on inserting various substances into the pericardium (soft tissue that surrounds the heart) itself. Arthur Vineberg in 1946 introduced the idea of a bypass by connecting left internal thoracic artery into the front wall of the left ventricle. Finally in 1956 one Charles Bailey successfully performed a coronary endarterectomies (instead of bypassing the blocked area, the blockage is striped away). The last and possibly most important piece happened by accident when Mason Sones mistakenly injected a contrast dye into the right coronary artery of a patient. He realized this method could be used for a coronary angiogram, which allows a doctor to X-ray and visualize arteries in the body. They were no longer working “blind”. Each of these doctors and each of these advances slowly perfected on the technique and it culminated in 1960 when the first CABG was performed after extensive training by four doctors lead by Robert Goetz. The operation was a success, but not without setbacks. The patient died 13 months later, but an autopsy revealed that the graft itself had held and the operation was not the cause of death.[7]

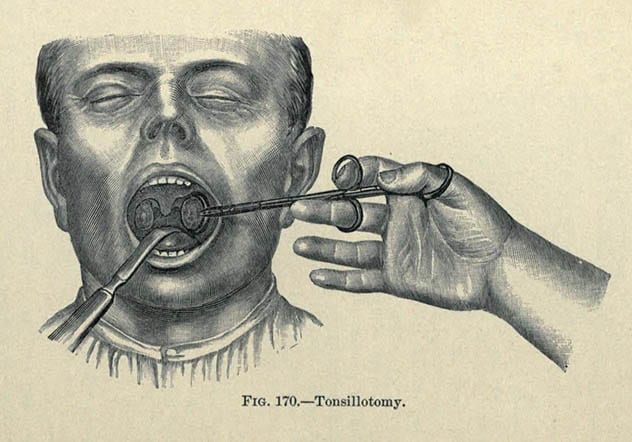

3 First Tonsillectomy: Common even in 1000 B.C.

A Tonsillectomy is the removal of the tonsils, two small glands in the back of the throat. In many cases this will be a child’s first exposure to the idea of a surgery when either they or a friend have their tonsils removed, usually because of infection and frequent sore throats. The origins of the surgery are ancient. Earliest reports describe the procedure preformed by ancient Hindus as far back as 1000 B.C. But perhaps the most detailed ancient account of Tonsillectomies comes from the Roman Cornelius Celsus in A.D. 40 who described how it was performed in his day with great detail. Namely, it was common for the doctor to bluntly remove the entire tonsil—by hand. The effects of removing the entire tonsil in this way were to be preferred over just cutting off a slice. This method was favored even into the 20th century.[8]

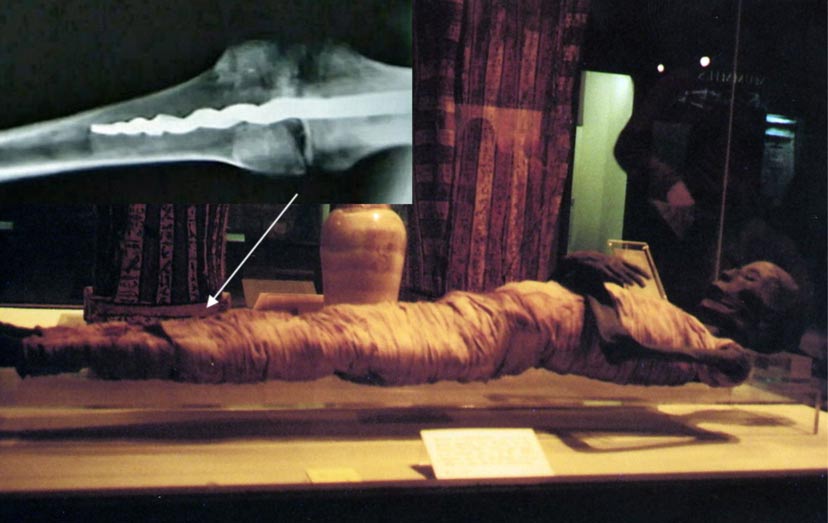

2 First Orthopaedic Surgery: A 3,000 year old Knee Pin

For decades an ancient Eqyption Mummy dating to around from the 11th-16th Centuries B.C. was in the possession of the Rosicrucian Museum in California. As far as preserved ancient bodies go, apparently unremarkable. In 1995, a examination of six of the Museum’s mummies included an X-ray and one mummy proved itself very remarkable. The mummy is called Usermontu, but that’s a case of stolen identity. Usermontu was a priest and his sarcophagus was labeled with his name and title, but at some point after his death his sarcophagus was reused for a new mummy. That new mummy was the one in the Museum’s possession. Having no known name for itself, it came to be called Usermontu all the same. When “Usermontu” was X-rayed, the scientists were surprised to discover a 9-inch metal pin in its left knee expertly placed. It was so unbelievable in fact that the head of the project, Professor Griggs, said, “I assumed at the time that the pin was modern. I thought we might be able to determine how the pin had been inserted into the leg, and perhaps even guess how recently it had been implanted into the bones. I just thought it would be an interesting footnote to say, ‘Somebody got an ancient mummy and put a modern pin in it to hold the leg together.’” The team drilled a small hole in the body large enough for a camera to be inserted to examine the pin and for samples to be collected. What they discovered was a resin similar in function to modern bone cement and ancient fat and textiles. The pin was not a modern addition, but was the result of a surgery performed 2,600 years ago. “We are amazed at the ability to create a pin with biomechanical principles that we still use today—rigid fixation of the bone, for example,” said Dr. Richard Jackson, a Utah county medical doctor involved with examining the Mummy. “It is beyond anything we anticipated for that time.” This surgery though, was not performed to give “Usermontu” a better life, but rather—a better afterlife. The ancient Egyptians believed that the physical body of a person was their vessel in the afterlife. Great care was taken to preserve and repair any damage so that the deceased would have a well working body to continue using. This operation, so carefully and expertly handled, was done after the patient’s death so that he would have a working knee again when he reached the afterlife.[9]

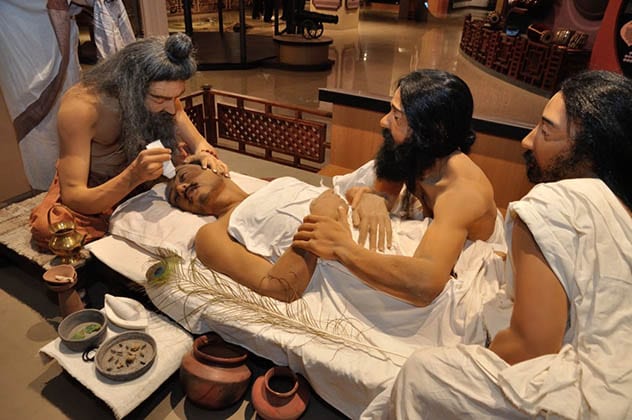

1 First Plastic Surgery: An Ancient Indian Nose Job

A common misconception about the term Plastic Surgery is that it refers to plastic material, but instead its actually based on the Greek word plastikos, which means “To Give Form” or “To Mold”. So it comes as no surprise then that the first cosmetic surgeries predate the plastic material by more than 1,500 years. The Sushruta Samhita, a foundational Indian medical book dated to the 6th century A.D., includes a description of many medical procedures. One such operation is described like this: “The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek, and turned back to cover the nose, keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils, so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of licorice, red sandal-wood and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton, and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it.” In total the Sushruta Samhita includes the descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, 121 medical instruments, and 300 surgical procedures. The medical procedure described above wasn’t replicated in the west until 1794 when a similar procedure was published in Gentleman’s Magazine of London, which described the surgery being used to reconstruct the nose of a mutilated cart-driver.[10] Top 10 Disturbing Facts About Doctors