10 Entroido CarnivalSpain

Entroido Carnival takes place in Laza, Spain, and lasts for three days. On the first day, men dress up in terrifying wooden masks and march through the street with whips. They represent the Galician taxmen who policed the townspeople in the 16th century. Get in their way or exist near them and you’re gonna get a whipping. Monday is the most violent day of the festival. It’s centered around a practice called farrapada (“ragging”). Muddy rags are thrown indiscriminately at anything with a pulse. However, the most feared participants of the day are those who carry sacks. They’ve spent time in the lead-up to the festival scooping up anthills and dumping them inside the sacks. Vinegar is poured over the bagged ants, which makes them particularly bitey. Fellow revelers (who now seriously lament bringing muddy rags to a vinegary ant fight) are chased down as the insects are hurled in their direction.[1] Things wind down on Tuesday with a satirical poem known as the testament of the donkey. Laza residents who have made errors during the year are individually lambasted and handed sections of donkey in the hope that it will somehow help them avoid repeating those errors.

9 Cotswold Olimpick Shin-KickingEngland

The annual Cotswold Olimpick Games are home to a variety of events. Many are just as archaic as the spelling of “Olympic.” You’re likely familiar with tug-of-war and Morris dancing. Piano smashing, you can figure out. However, the festival’s most popular and violent event is the shin-kicking championship. Matches are a one-on-one affair. Competitors place their hands on each other’s shoulders. In that position, they must wrestle for leverage to unleash a flurry of kicks to their opponent’s shins.[2] The bout ends when one competitor can take no more. At this point, “sufficient” is all they need state. It’s how the British gentleman says, “Mommy, make it stop.” The Cotswold Olimpick Games are believed to have started in 1622. Back then, things could get bloody. It’s believed that iron-capped boots were commonly worn and that competitors would condition their shinbones throughout the year by smashing them with objects such as hammers. Nowadays, it’s a classy affair. Iron-capped boots aren’t allowed, and competitors’ trouser legs are stuffed with straw for cushioning. Also, they wear shepherds’ smocks, which are essentially the same as lab coats. It makes the whole thing seem like a nerd fight over which series of Star Trek was the best.

8 Agni KeliIndia

In Mangalore, India, devout Hindus gather to appease the goddess Durga by throwing burning palm leaves at each other. Participants meet at the local river for a communal and spiritually significant cleansing. Then it’s time to play some flaming dodgeball. Participants divide into two groups. From there, palm-built torches are hurled at the opposing side. The more people are hit, the more Durga is impressed. Officially, each participant is only allowed five throws, but the fire fight lasts roughly 15 minutes. This means that a lot of torches are being recycled, indicating that Durga’s a chilled-out goddess when it comes to rules. Nevertheless, there are referees present to make sure that people don’t get too badly injured . . . while being pelted with flaming palm leaves. After the 15 minutes have elapsed, the participants walk toward the Kateel Durgaparameshwari Temple where another quick fire fight takes place before injuries are doused with holy water.[3]

7 Rouketopolemos (The Rocket War)Greece

Easter night in Vrontados, Greece, is not a peaceful time. Two rival churches (Saint Mark and Panagia Erithiani) have been competing with each other for centuries. Every year, both churches attempt to settle the score by launching fireworks in the other’s direction. The loser is the church whose bell gets hit first. And for the winner—bragging rights, we guess. It’s just fun to find an excuse to shoot fireworks at bells. Also, recording the bell hits isn’t done scientifically, meaning both churches claim victory every year.[4] Not everyone is a fan of the festivities. The surrounding buildings have to be protected with metal sheets, or they will suffer significant damage. Fires are often started, the worst of which have led to death. In 2016, the event was canceled due to safety concerns. One local man is quoted as saying, “Many people have complaints about the damages that rocket war causes every year. But those people are not a lot, only 20, I think. I hope . . . this tradition will be continued.”

6 The Battle of the OrangesItaly

The origin of the annual Battle of the Oranges in Ivrea, Italy, is unclear. The legend goes that around the 12th century, the city was ruled by a particularly nasty marquis. Mad on power, he attempted to rape a local miller’s daughter. She ended up decapitating him and inspired a revolt in which the palace was burned to the ground. The festival is a reenactment of this revolt. Only instead of stones and whatever other projectiles were used against the marquis’s men, now the battle is solely fought with oranges.[5] Crates of the fruit are stacked in the street for anyone who wishes to take part in the festivities. From there, you simply wait for the marquis’s men to come through, guided by surprisingly obedient (yet no doubt terrified) horses. Although they do return fire, the most likely injury you’ll endure will come from friendlies as oranges are lobbed from one side to another. If you’ve ever had an orange thrown at you, you know that they can leave an impressive bruise. At least 70 people were treated for their injuries last year alone.

5 Bolas De FuegoEl Salvador

In 1658, the volcanic eruption of El Playon destroyed the town of Nixapa in El Salvador. Survivors relocated to what is modern-day Nejapa. The Bolas de Fuego event is held every August 31 in commemoration. The name translates to “Balls of Fire” and is in no way misleading. In the three months leading up to the event, participants construct over 1,500 apple-sized balls of kerosene-soaked cotton. They’re also wrapped in wire. That way, they don’t lose their shape and can really smack into their targets. Amazed tourists hide behind their camera phones as the fireballs begin to sail through the night sky. Most participants’ faces are also daubed with intimidating face paint—just in case the fireballs weren’t enough to get your heart rate up.[6] Although the footage of the two-hour battle looks extreme (and the balls regularly stray into the crowd of spectators), serious injuries are surprisingly low.

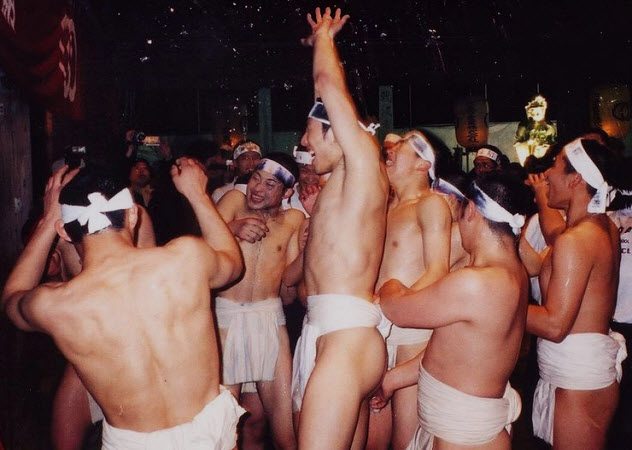

4 Saidai-ji Eyo Hadaka Matsuri (Festival Of Naked Fighting Men)Japan

Hadaka Matsuri roughly translates to “Naked Festival.” Many have popped up in Japan over the years, but none are more famous than Saidai-ji Eyo Hadaka Matsuri. It takes place every year at Saidaiji Temple in Okayama. Technically, no one’s really naked. The 9,000 exclusively male participants all wear loincloths—identical to those worn by sumo wrestlers. From a raised window, a priest throws around 100 sacred sticks into the crowd. It’s thought that luck will be bestowed on any man who manages to shove a stick into a rice-filled box called a masu.[7] It’s not an easy task, considering that the person who catches the stick then has to wrestle the rest of the mob of almost naked men until the stick is safely posted. Really, winning this game is the luckiest thing you’ll ever do. In fact, participants have occasionally been tremendously unlucky—as they were crushed to death on the temple’s floor.

3 Festa De Sao Joao Do PortoPortugal

The festival’s official English name is the Festival of St. John of Porto. It takes place every year on June 23 and attracts thousands of people to the Portuguese city’s center. The date is likely an indication of the festival’s pagan roots. It’s around the time of the harvest when many people would stock up on leeks and garlic. Leeks were also a symbol of fertility, owing in part to their somewhat phallic shape. The tradition follows that the leeks would be whacked on the heads of loved ones to aid their sexual performance.[8] In the 20th century, as they were presumably sick of the annual bruising, locals switched over to using plastic hammers instead of leeks. The hammers create comical whistling sounds on impact and are relatively painless. Garlic is still a large part of the festivities. You can thrust cloves in front of people’s faces to communicate how much you like them. Don’t try this anywhere but Porto, though. You’re likely to get a much nastier blow to the head if you do.

2 TakanakuyPeru

Takanakuy roughly means “when the blood is boiling.” It takes place in the Chumbivilcas Province of Peru on Christmas Day. During the ceremonial proceedings, five traditional characters are portrayed, including Negro. The character is that of a slave master during the Peruvian colonial period who dances in circles like a rooster. These rituals build nicely to the main event of the festivities—the fighting. The tiny province of Chumbivilcas, with a population of around 300, sees its greatest influx of tourists during the event. Over 3,000 people flock to see the face-punching. Feuds that have developed over the year are settled here, and all are welcome to participate. It’s not uncommon to see women and children take part, but it’s mostly men. Fists are wrapped in cloths, and the contest ends when an opponent is knocked out or the referee intervenes. The referees also carry whips to keep the fighters and the crowd from getting too frenzied.[9]

1 The Abare FestivalJapan

Also known as the Fire and Violence Festival, the Abare Festival is held on the first Friday and Saturday of July. The bizarre rituals involved are largely fueled by sake, and it is encouraged to cause chaos as this will please Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the Shinto god of sea and storms. On Friday, a lantern parade takes place through the village of Ushitsu, Japan, and ends at the pier. There, the lantern carriers are greeted by large fires that are suspended on top of poles. As they burn, their embers glide down like snowflakes. Men and boys dance underneath and play drums, bells, and flutes.[10] Nothing beats the chaotic flute. On the second night, the focus is on the destruction of two portable shrines as revelers march to the stationary Yasaka Shrine. The portables are thrown into roads and rivers and endure their fair share of fire, too. Whatever remains is placed in front of Yasaka Shrine and is smashed with flaming torches for hours on end to gain spiritual favor. David Dee likes celebrations that don’t end with hospital trips. Read more of his articles at CultureRoast.com, follow him on Twitter, and like him on Facebook.