Sometimes, however, Mother Nature got day-drunk and cooked up something really weird, even according to those scientists who uncover strange old things for a living. 10 Amazing Evolutionary Discoveries In Prehistoric Creatures

10 The Tooth-Beaked Dinosaur-Bird

Birds are basically dinosaurs. But the transition between the two happened in such a gradual, piecemeal way that sorting it out is a huge headache. A new creature has been discovered from this headache-inducing period of animal evolution: the Ichthyornis dispar. It’s a missing link–type animal known as a “stem bird” because it straddles the line (and weirdly) between dinosaur and bird. It occupied Kansas 100 million years ago—in the days when Kansas was an inland sea. And even though it had a long beak, I. dispar hadn’t yet lost its dinosaurian teeth. Instead, it combined the best of both worlds to terrorize ancient sea life. It pinched fish from the water with its birdly pincer beak and then crushed its prey into a delicious paste with its well-muscled dinosaurian jaw.[1] What’s inside its head is just as important. I. dispar had a surprisingly large brain to go with its imposing beak. This doesn’t agree with hypotheses which argue that jaw muscles should shrink as skulls (and brains) grow more massive. It’s no wonder that the smart and deadly I. dispar and its ilk had a bright future.

9 The 1,000-Kilogram (2,200 lb) Guinea Pig That Stabbed Enemies With Its Massive Tusks

Three million years ago, prehistoric rodents packed serious muscle. The Uruguayan Josephoartigasia monesi was the mightiest, with a hulking 1,000-kilogram (2,200 lb) body that could stand shoulder to shoulder with a bull. Of all the rodents’ distinctive features, oversized front teeth are the most obvious. The maxed-out guinea pig J. monesi was a king among beasts in dental regards as well, with 30-centimeter (12 in) incisors that resembled tusks more than rodent teeth. Just seeing these teeth wasn’t enough for scientists, who wanted to know how they handled. Using CT scans, virtual reconstructions, and computer simulations, researchers recreated J. monesi’s bite and found it was capable of delivering a bite about as strong as a tiger’s—even though J. monesi’s chompers could bear forces three times as great.[2] That’s probably because it did more than bite. J. monesi probably used its tusklike incisors to gore anything that ticked it off. The creature also used its teeth to root about the ground and dig up hidden foodstuffs like an elephant would. Overall, very impressive for the cousin of the guinea pig.

8 The Amazing Pig-Nosed Turtle

Turtles are among the planet’s oldest creatures, having graced Earth for more than 250 million years. However, despite sizing disagreements, nature has been fairly conservative with prehistoric turtle design. The exception? A slight evolutionary hiccup 76 million years ago which produced the goofy, pig-nosed Arvinachelys goldeni. The turtle inhabited Utah way back in the day when North America was a big island known as Laramidia. Utah itself also looked radically different during the Cretaceous. Its deserts were replaced by hot and humid swamps which extended into floodplains, bayous, and rivers for the pig-snouted turtle to splash in.[3] A. goldeni deepens an existing evolutionary enigma from Laramidia. Creatures from the north and south ended up looking too different. This showcased an unexpected level of differentiation, especially with the lack of obvious factors separating the two populations. This mystery was not at all cleared up by the appearance of the pig-turtle.

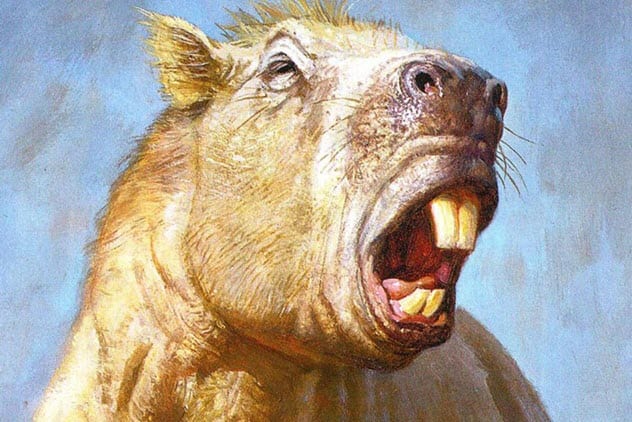

7 The Pug-Faced Mega-Hyena

Pachycrocuta brevirostris is known as the “short-faced hyena” thanks to its snub-nosed pug face. But don’t let the goofy visage fool you. P. brevirostris is the baddest hyena to ever walk the Earth. It’s a hyena with the mass of a lion. And all that hateful mass is packed into a body no taller than that of today’s spotted hyena. P. brevirostris‘s dense, chunky body, stout limbs, and jaw were built for scavenging supremacy. Its low, stooping stature gave it excellent leverage to tear slabs of meat from large, meaty carcasses. Then P. brevirostris dragged its meal away to eat in peace and safety before repeating the hit-and-run maneuver.[4] P. brevirostris forced its way onto the evolutionary scene about three million years ago in Africa and Asia. Then it sauntered into Europe about a million years later. Unfortunately, that coincides with similarly minded migrations undertaken by our ancestors. There’s evidence that early man and hyena inhabited the same places. This wasn’t so great for our side, according to mangled Homo erectus remains from the Dragon Bone Hill site in China.

6 The Dolphin That Thought It Was A Swordfish

Scores of strange creatures appear and disappear every time the oceans warm and cool. Among the weirdest of these animals was a dolphin that attacked prey with a swordlike nose—like a swordfish. The longest-snouted mammal of all time, Zarhachis flagellator arrived at the evolutionary party 20 million years ago during the Neogene Period. This creature sported a schnoz five times longer than its skull. This Pinocchio nose of a snout was more than 1 meter (3 ft) long, and it swept through the water as Z. flagellator searched for prey. Once it locked onto an unfortunate meal, Z. flagellator clubbed its victim silly with its weaponized snout. Scientists know this after studying the structure of the snout to estimate the forces it could withstand. Researchers also compared Z. flagellator‘s physiology to similar prehistoric dolphins as well as modern marlins.[5] But the climate eventually snuffed out Z. flagellator around the beginning of the Pliocene Epoch. A brutal glaciation period altered the creatures’ habitat and food supply, wiping out the long-snouts by 2.5 million years ago. 15 Unusual Prehistoric Creatures

5 The Cold-Blooded Goat

Myotragus balearicus, a 46-centimeter-tall (18 in) dwarf goat from the Balearic Islands, survived millions of years by adopting a strategy from the reptilian evolutionary playbook: cold-bloodedness. Its ancient goat bones stunned scientists, who had never expected to find the treelike growth rings within. Since warm-blooded creatures are continually building their bones, they don’t exhibit this skeletal quirk. But cold-blooded animals grow their bones in spurts when resources allow. Those resources didn’t allow much wiggle room on the barren, unfruitful island of Majorca. So the Balearic goat became smaller and borrowed some reptilian biology. Now it could laze around in the sun all day and not constantly worry about food. However, its reduced size and metabolic rate came with a drawback: M. balearicus couldn’t fight or even effectively run away from its predators. Luckily for the goat, it didn’t have any predators on the little island.[6] So this puny, defenseless, nonathletic goat enjoyed its Mediterranean paradise for 5.2 million years; that’s twice the average reign of mammal species. M. balearicus was eventually killed off 3,000 years ago when humans arrived.

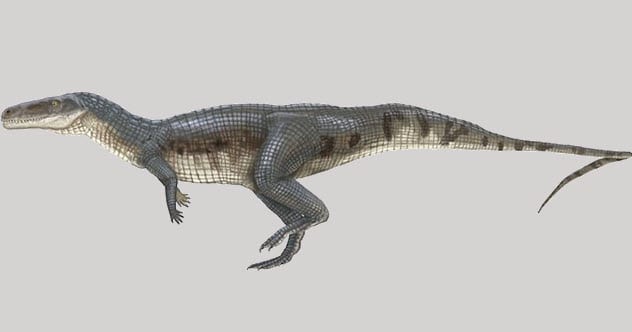

4 The Walking Crocodilian

Dinosaur lore is full of mysteries. For example, how did dinosaurs survive their reptilian competitors, the proto-crocodilian-like rauisuchians? Unlike crocodiles with their splayed limbs, rauisuchians (related to a predecessor of crocodiles) held their legs straight below their bodies. The more upright orientation would have made walking easier and faster while traveling on four feet as rauisuchians were apparently wont to do. This quadrupedal bias was one of the reasons that dinosaurs outlived their Triassic fellows. It seemed that dinosaurs had the advantage of bipedalism, which is a faster and more efficient form of locomotion. But science has found out that at least some of the rauisuchians also walked on two feet. One specimen that did so is the dinosaur-impostor Poposaurus gracilis. The 225-million-year-old P. gracilis was approximately 4 meters (13 ft) long with a mouthful of backward-curved teeth to shred its prey. It had comically small arms but made up for them with a long, tapered tail which allowed the creature to walk and run upright like its more resilient dinosaurian counterparts. Thanks to P. gracilis, the mystery of dinosauric dominance is reignited.[7]

3 The Ferociously Vegetarian Cave Bear

The European cave bear, so-called for its fondness of caves, weighed up to 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) and rivaled the largest living bears. But unlike modern omnivorous, picnic basket–snatching bears, the ancient variant was “exclusively herbivorous.” These bears roamed Europe and Asia from 300,000 to 25,000 years ago, dying out around the Last Glacial Maximum. Even though its environment was dry and cold, Ursus spelaeus managed to forage for enough vegetation to support its large, 3.5-meter-long (11.5 ft) frame on salad. How do scientists know? They analyzed the bones—some of which date back to nearly 50,000 years ago—of six bears discovered at three cave sites in Romania. Scientists zoomed in on the fossilized collagen within the skeletal remains and compared it to bone collagen from carnivores, herbivores, and cave bears from other parts of Europe. Based on the ratio of different types of nitrogen in the amino acids within the collagen, researchers concluded that U. spelaeus was a strict vegetarian.[8]

2 The Armored Basking Fish

The armored fish (placoderm) Titanichthys was one of the largest sea dwellers of the Devonian Period 380 million years ago. Titanichthys grew to more than 5 meters (16 ft) in length and boasted a 1-meter-long (3 ft) jaw. But that jaw was a surprisingly weak and toothless one with no cutting edge. So, if its jaw wasn’t built for combat or ripping bloody chunks out of its prey, what was it designed for? It turns out that this fearsome fish wasn’t so terrifying after all. Instead, it made its living as a “suspension” feeder, like a basking shark. For all its apparent ferocity, Titanichthys employed a lazy (but efficient) feeding method called “continuous ram feeding.” It just floated about with its mouth gaping open, scooping up the tiny critters that inhabited an ancient sea that is now the Moroccan Sahara Desert.[9] The trendsetting Titanichthys is the earliest known species to “bask,” preempting the more famous basking animals, like baleen whales, by a whopping 350 million years.

1 The Anchovy With A Sabertooth

Fossils sometimes sit in museums for many years before being properly described. Two such fossils sat on a shelf for 20 years before recently revealing that anchovies weren’t always the little chumps they are today. While modern anchovies eat plankton and grow to about 15 centimeters (6 in) long, the prehistoric Monosmilus chureloides was about 1 meter (3 ft) long and ate other fish. It also had a sabertooth—as in a single sabertooth poking from its upper jaw to complement a row of sharp fangs on its lower jaw. That’s right, M. chureloides was a predatory anchovy that impaled its prey.[10] The 45-million-year-old M. chureloides hails from the Paleogene when a surprising number of fish transformed into ruthless killers. The niche for ferocious fishes opened up when larger sea terrors were killed off by the dinosaur-obliterating asteroid 66 million years ago. Like its brethren species, the ancient anchovy from the Eocene Epoch evolved into a beast to fill that niche and feast on lesser fishes. 10 Strange Features Recently Discovered In Prehistoric Creatures About The Author: Ivan writes things for the Internet. You can contact him at [email protected]