The country is home to some of the oldest, biggest, and rarest discoveries known to science. Ancient ancestors also present their many mysteries woven into the ruins, DNA, and macabre skeletons they left behind.

10 The Valongo Formation

Outside the town of Arouca, supersized bugs inhabit a tile quarry. The goobers died 450 million years ago and formed a fossil bed known as the Valongo Formation. Trilobites scurried about on ancient seafloors, and their fossils are not rare or, in this case, of good quality. But when they were unearthed in 2009, the creatures were the biggest trilobites ever found on Earth. Usually, the hard-shelled marine animals grew to thumbnail size and bigger, with one rare trilobite measuring 71 centimeters (28 in) long. The biggest Arouca specimen hit the world record at 76 centimeters (30 in). Other species present were extraordinarily big, too. It stirred debates about why several had members ranging from normal to gigantic. One theory suggests that they often molted, shedding their exoskeletons as they grew throughout their lives. But it was not just the unusual dimensions of the group that made it a UNESCO site. It was their sheer numbers.[1] In some places, two dozen fossils were stacked on top of each other. Why they came together is unclear, but the mass die-off could add new insights into the behavior and possibly environmental changes that led this group to their graves.

9 Oldest Crocodilian Eggs

In 2017, researchers dangled on cliffs near Lourinha. They had been excavating dinosaur nests for some time. But on this particular occasion, they found eggs of a different nature. Mysteriously wedged between the dinosaur eggs were those belonging to a crocodilian. Deposited over 152 million years ago, the clutch officially has the earliest crocodilian eggs in history. The remains were pristine enough to allow researchers to calculate the mother’s size. The 2-meter-long (6 ft) adult was not a true crocodile but a close relative. She belonged to a collection of prehistoric crocodilian species clumped together as “crocodylomorphs.”[2] These were the ancestors of the modern predators scaring animals at water holes the world over. In the past, crocodilians’ looks were varied and they haunted different habitats and prey. But the Lourinha eggs were modern enough to prove that little has changed in that department.

8 Unknown Bronze Age People

Excavations in the Alentejo plain recently unearthed traces of an ancient settlement. This was no tiny village with a cow. Archaeologists found imposing battle walls and fortifications that once covered 17 hectares. The fortifications included a double stone wall, ramps, and bastions. In 2016, the site also revealed the enigmatic stone art referred to as “cup marks” which decorate western Europe. Called Outeiro do Circo, the site allows a glimpse of those who lived in prehistoric Portugal long before the country’s history became famous for its colonial exploits. The builders of the monumental settlement left only a few clues about themselves. They appeared to belong to a larger Late Bronze Age (1250–850 BC) community, one that consisted of several smaller satellites in the area. Outeiro do Circo was clearly important and perhaps faced some sort of threat—a lot of effort went into making the massive wall. To strengthen the foundations, people lugged huge amounts of wood up the hill to the wall and set it on fire.[3]

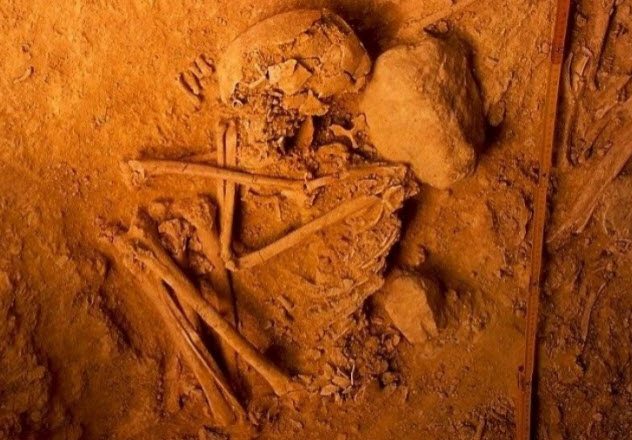

7 Successful Steppe Resistance

Around 6,000 years ago, people from the Eurasian Steppe arrived in Europe. Ancient DNA showed that they intermingled heavily with the locals. But violent finds suggest that it was a forceful arrival rather than a friendly merger. Cultural domination was further established by the fact that their Indo-European language spread throughout Europe. However, one place held its own against the invaders. In 2017, researchers wanted to see if the Eurasians had anything to do with a sudden cultural shift that occurred at the time on the Iberian Peninsula. The team extracted DNA from 14 skeletons from Portugal, including individuals from the Neolithic and Bronze Age.[4] The ancient Iberian genes showed a subtle difference between the Neolithic and Bronze Age groups. Any Eurasian genes likely resulted from a small migration into the region and not an invasion. The Iberian cultural shift was entirely their own. The lack of a takeover can explain why Iberia was home to languages that could not be traced back to any Indo-European language. How the Iberians kept the invaders out when everyone else failed remains a riddle.

6 Medieval Madura Foot

Archaeologists recently investigated a medieval cemetery in Estremoz in southern Portugal and found a man with unusual injuries. His left foot was mangled—not by violence or an accident but because of disease. Holes perforated the heel bone, which was fused with the ankle, and all the bones in the middle of his foot showed damage. The disease also affected the lower leg. Experts diagnosed it as a probable case of Madura foot. First reported in Madura, India, during the 19th century, it has never been seen in medieval Europe. This painful condition is caused by a fungus contracted when a person walks on infected soil. After entering a foot wound, the fungus wreaks havoc within bones and amputation was most likely the only way to survive. The Portuguese case is odd and rare. One of only three ancient cases, it has never been recorded in the region. It is possible that the man was infected elsewhere, but researchers believe that the Medieval Climatic Anomaly (AD 1000–1400) warmed the soil enough to theoretically support the survival of the fungus in southern Portugal.[5]

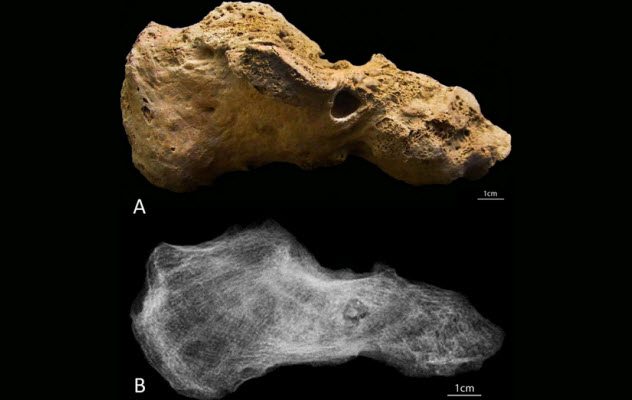

5 Tumor With Teeth

During 2010–2011 excavations, a burial in Lisbon brought a queasy addition to the surface. A middle-aged woman from the 15th century had a tumor near her pelvis, and the growth had human teeth. Researchers were working at the Church and Convent of Carmo when they happened upon the cyst. Known as a teratoma, this common ovarian tumor forms when cells earmarked to become eggs go crazy. Instead of forming eggs, the cells build human parts such as hair, bones, and teeth. In this case, there were five recognizable molars and an indication of bones. The tumor was big, measuring 4.3 centimeters (1.7 in) wide. But it is impossible to say if the woman was affected by the mass.[6] Some modern cases give no symptoms, while others cause severe pain. Since many teratomas develop only as tissue balls, the toothy tumor is a valuable chance to study the more bizarre ancient cases.

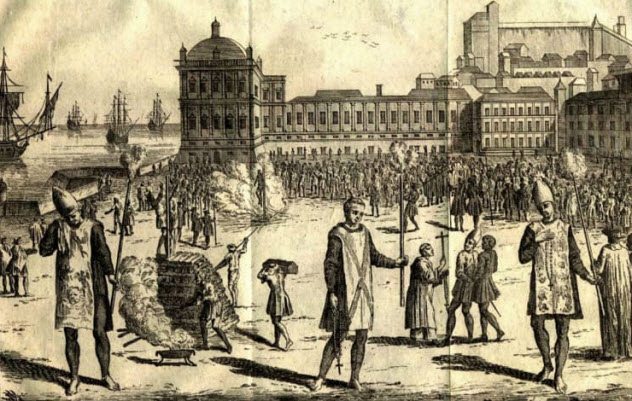

4 Bodies In The Trash

Another archaeological dig, this time outside of Lisbon, found a dozen bodies. This was no orderly cemetery. The nine women and three men had been discarded in a known trash site used between 1568 and 1634. Their identities remain unclear, but the location provides a big clue. The dumpster was once called the Jail Cleaning Yard and used by the Inquisition Court in Evora. The Portuguese Inquisition was a brutal affair staged against the Jews. Beginning in 1536, it outlawed Jewish practices and most of the people arrested were accused of continuing their faith in secret. Some died from inhumane prison conditions, and hundreds more died at the stake. Upon death, Jews were also not allowed to have their customary burials.[7] The 12 skeletons, found during the 2007–08 renovations of the court building, also had no sign of formal burial. On the contrary, they had been thrown away like garbage. Everything points to the small group being Jewish victims of the Portuguese Inquisition.

3 Neolithic Telescopes

In Portugal’s Carregal do Sal, there are tombs that pulled double duty. Apart from housing the dead, some were constructed in a special way—to make stars visible that would otherwise be invisible to the naked eye. The megalithic monuments were dark enough within to allow an amplified view of the night sky. A person just had to stand in the middle of the tomb and gaze outside through the entrance passage. This was not idleness at its best. Astronomers believe that there was an important reason the community needed to discern certain stars 6,000 years ago. In this case, it was likely one called Aldebaran. Thirteen of Carregal do Sal’s graves captured this bright star. Since it rose near the end of April or at the start of May, it provided a trustworthy signal to start their summer migration. But why combine astronomy with a cemetery? It is possible that Aldebaran’s importance extended beyond being a calendar day and perhaps was a guardian to the deceased or a visible “heaven.”[8]

2 Amputation On The Living

A truly horrifying aspect of medieval Portugal came to light in 2001. A necropolis attached to the town of Estremoz yielded 97 skeletons. Three of them showed injuries of a barbaric nature. Found side by side, the men’s hands and feet were cut off. Archaeologists found the missing parts buried near or under the bodies. The bones of the hands and feet were together, meaning that the body parts did not somehow scatter after death. Instead, they were placed in the grave as amputated pieces. Worse, cut marks on the skeletons showed that the amputations occurred while the young men were still alive. They probably died of blood loss soon after. One man suffered badly. His skeleton showed a failed attempt to hack his lower legs before another blow was successful. During this time between the 13th and 15th centuries, thieves often lost their hands by way of punishment. But finding three people together with all extremities removed is a medieval first. The men could have been torture victims but were more likely criminals guilty of particularly serious crimes.[9]

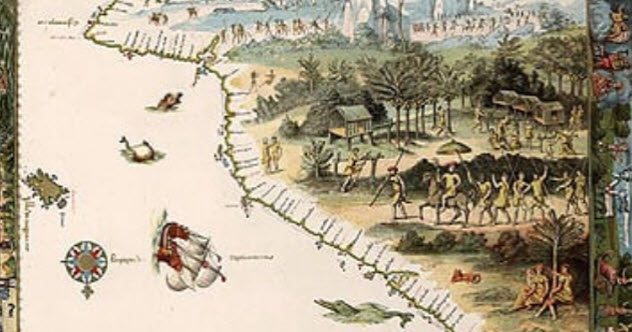

1 Portugal Discovered Australia

Two ancient pieces of evidence could change Australian history. One is a 400-year-old manuscript and the other a set of charts drawn in the early 16th century. Popular history dictates that Captain James Cook from England discovered Australia in the 18th century. However, the manuscript dates to an earlier time (1580–1620) and contains a curious creature resembling a kangaroo or wallaby. At its earliest, it even predates the guy who officially beat Cook back in 1606, the Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon. Some experts claim that the animal is a rearing deer. But if the chart set can be confirmed, it will wipe the Dutch off the map completely. Discovered in an Australian bookshop in 1999, the charts show a coastline similar to Australia’s. The handmade maps were written in Portuguese in the 1520s, nearly 250 years before Cook drifted into the picture.[10] Software corrected an error made by later cartographers who incorrectly arranged the pieces. When one chart was rotated 90 degrees, the collective map matched a massive stretch of Australia’s eastern coast. Perhaps, someday, a statue will honor Portuguese explorer Cristovao Mendonca, the creator of the charts, as the first European to arrive in Australia. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages