Somewhat weird and creepy but somewhat neat and sweet, the gnome’s presence makes the house a unique stop on any neighborhood walk. They’ve become so notorious that television shows have parodied the trend for years. Some even suggest these garden guys have secret lives that flourish after the sun goes down and the homeowners go to bed. As it turns out, there’s actually quite an interesting history behind the proliferation of garden gnomes. The trend started far earlier than you probably think. And there’s more depth here than just your weird neighbor’s decision to grace their garden with a special pal. Below are ten surprising facts about lawn gnomes you never thought you’d need. So now, the next time you pass by that house in your neighborhood, you’ll know all about where that little guy out front came from.

10 The Romans Pioneered the Lawn Gnome Trend

When in Rome, do as the, uh, garden gnomes do? Of course, ancient Romans didn’t know about gnomes in the same way we do today. But residents at that time still used small statues to watch over their crops and property. Taken this way, these garden guardians were the world’s first lawn ornaments. And they had a purpose! For the Romans, the point of carefully-placed garden status was to hold back evil spirits and guarantee a bountiful harvest season. Watch this video on YouTube The most common Roman garden deity was Priapus. He was the god of vegetable gardens, beehives, vineyards, and animal flocks, and he was said to look over living creatures and harvest periods. He was essentially a fertility god. Often, statues from that time period depicted him as a small, dwarf-like man. That’s very ironic, considering the look of current-day gnomes is so similar to how those ancient Romans would have seen him. And with so many gods who were said to hold so many special responsibilities, Priapus’s role is very specific. Perhaps he was the true great-great-great-grandfather of today’s direct descendant lawn gnome offspring![1]

9 Knowledge of Gnomes Begins to Sweep Across Europe

Paracelsus was a well-known alchemist and philosopher in the 16th century. As part of his work, the Swiss man researched the four basic elements of the world: water, fire, air, and earth. Gnomes, Paracelsus argued, were the guardians of the earth. The famous alchemist believed the little beings could pass through rock, earth, and vegetation while warding off demonic spirits. Paracelsus’s inspiration for this was found in The Iliad. The Swiss philosopher believed gnomes were a natural extension of the pygmies depicted in the Greek literary masterpiece. Lawn gnomes, as we know them, didn’t take hold during Paracelsus’s life, but his impactful work on this theory lived on long after his death in 1541. Over the next few centuries, the idea of gnomes as garden guardians began to strongly percolate among people across Europe as more people sought their supposed comfort. Less than a century after Paracelsus’s death, residents across western Europe were placing statues in their gardens. In Italy, these little stone creatures were known as “gobbi,” which means “dwarf” or “hunchback.” Inspired by Paracelsus’s four elements and their Roman precursors, Italian property owners used the artifacts to seek land blessings. By the 1700s, those “gobbi” transitioned into becoming “house dwarves” across much of the continent. At the time, these dwarves were little porcelain creatures that alternated between staying inside homes (as dwarves) and being set out in gardens (and designated as gnomes). In both cases, residents believed the statues brought good fortune. The phenomenon was popular across Europe well into the 19th century. Then, the first garden gnomes as we know them today began to appear.[2]

8 The (Real-Life) Hermit in the Garden

Roman statues and the spread of dwarf designs across Europe may have been enough on their own. But simultaneously, wealthy landowners were using the real thing: human hermits! Through the European papacy and into the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, rich people across the continent would hire real humans to live in their expansive lands. These hired hands would live alone in a dingy hovel and tend to the gardens in solitude. Historians now believe this phenomenon can be traced back to ancient Rome too. Watch this video on YouTube During Emperor Hadrian’s reign, he built a small cottage in one of his gardens and hired a man to live there as an overseer. Over time, this trend morphed into the “hermit in the garden” move many wealthy Europeans flocked to by the turn of the 19th century. By that point, the elite landowning class in Georgian England was all in on garden guards. Property owners hired hermits and sent them into these large, enclosed outdoor spaces. The fad had some bizarre elements too. British historian Gordon Campbell’s book The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome documents how some hermits rarely bathed, never spoke, and stayed in solitary confinement (while taking a salary!) for up to seven years at a time. Some even dressed like dwarves and druids of old to give the trend a historic flare for their bosses. Thankfully, the trend faded well before the 20th century. By then, the human hermits were mercifully replaced by small statues that were symbolic and harmless in their solitude.[3]

7 Garden Gnomes Go Viral in 19th Century England

By the early 1800s, individual garden gnomes started taking hold in homes across Germany. During that time, a British man visited Nuremberg. Impressed with the gnomes, he decided to send some gnomes back to his English countryside home. Following this German jaunt, Sir Charles Isham landed in England with 21 terracotta gnomes meant for his personal garden. The man felt these fake gnomes were a more humane option than the real-life hermits wasting away in the lands of his rich neighbors. And they were! But they weren’t very popular at first. Instead of a viral sensation, it took a while for the trend to take hold. In fact, Isham’s own daughters thought the gnomes were tacky. Over time, they got rid of twenty of the creatures. Thus, one final gnome remained alone to guard over Isham’s garden. The girls liked him enough to keep him around. They even named the terracotta creature “Lampy.” By that time, Isham’s neighbors began to take notice of the gnome’s presence. Lampy was smaller, cheaper, and far easier to care for than the human hermits that had been so popular in wealthy spaces across England. Soon, Isham’s neighbors began bringing out their own gnomes to compete with Lampy’s pioneering presence. While his idea hadn’t been popular at first, Isham’s persistence—and his daughters’ foresight to keep Lampy—kicked off a garden gnome trend that swept across the British Isles in the 19th century.[4]

6 Gnomes Become Big Business

Isham may have brought gnomes to prominence in England, but they were already popular back in Germany. Through the 1800s, families across the Bavarian state began making and showing off what would later be known as today’s garden gnomes. But it still took years for the business community to catch on. Enterprise came to the gnome world in the late 19th century when artisan Philip Griebel realized the market’s potential. Griebel had been an amateur craftsman and sculptor previously known for creating animal head models. But with the gnomes, he saw a great new business opportunity. In Leipzig, he began producing his signature Gräfenroda garden gnome en masse. His business quickly grew as more German homes caught onto the trend. He would also show off his wares at the local Leipzig Trade Fair, further promoting the adorable and intricate garden watchers. Griebel used the proceeds from his lucrative trade to build a factory meant for producing these gnomes at a far larger scale. By the end of the 1800s, Greibel’s factory was producing more than 300 different garden gnome characters in several different sizes. The timing worked out perfectly in the craftsman’s favor too. Isham’s England push and growing international interest in the gnomes came together to rocket Griebel’s business into the stratosphere. From there, the gnomes we now recognize were solidified in popular culture. Today, Gräfenroda still praises Griebel’s foresight and hard work to balloon the trend.[5]

5 Gnome Production Craters During the War, but…

For a while, Grieibel’s bet on garden gnomes paid off throughout Germany. Families of all financial classes were keen on adorning their homes and gardens with the lovable little creatures. But then something terrible happened: World War I. The mid-1910s war shut down pretty much all industrial production throughout Germany. The nation needed those factories producing armaments and other war supplies. Griebel’s Leipzig production line wasn’t immune to the shutdown, and gnome production cratered during the war. Garden gnomes became a luxury item—unnecessary for all—and difficult for even the richest to afford. Even after World War I ended, sanctions against Germany in the 1920s and a global economic catastrophe in the 1930s kept gnomes out of the public consciousness. But then, in 1937, something lucky happened: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released. The American animated film was a massive hit in many parts of the world, Germany included. The dwarves’ gnome-like appearance and likable characteristics thrust gnomes back into the public’s collective minds. And even though World War II was destined to hit Germany and the rest of Europe soon after that, the movie’s lasting impact kept garden gnomes front of mind for many families. After scuffling through the postwar period, gnomes were back in Europe. Then, their popularity spread all across the developed world.[6]

4 The Gnome Evolves as More People Embrace It

Griebel’s bet on the business potential of garden gnomes proved to have a lasting impact. However, things still had to change considerably in the years since he went into factory production. Centuries ago, the precursors to these garden gnomes were sometimes as high as six feet tall. That didn’t work for Griebel’s mass production enterprise, though. When he went into overdrive making gnomes, they were small—often between three and six inches (8 to 16 centimeters) tall. The tiny creatures also weren’t tied to any specific backstory. No mythology or lore was included with their creation, and Griebel never explained why they looked like they did. But after Snow White, the dwarves’ costumes, backstories, and personalities began to seep into gnome culture. Factories seeking to capitalize on Griebel’s business savvy began to produce more intricate gnomes with deeper and more fleshed-out histories. The mythology of Disney’s animated dwarves blended into the gnome world. Designers gave gnomes specific personalities and traits. Technology continued to improve, allowing artisans to make far more detailed sculptures. Sensing an opening for new products, other craftsmen made female garden gnomes. The creatures began to be produced in bigger sizes too. People loved the improvements at every turn. Griebel couldn’t have predicted it when he began producing them at scale, but over the post-war period, these new gnomes were a hit. They quickly became more closely related to the lawn gnomes we know today.[7]

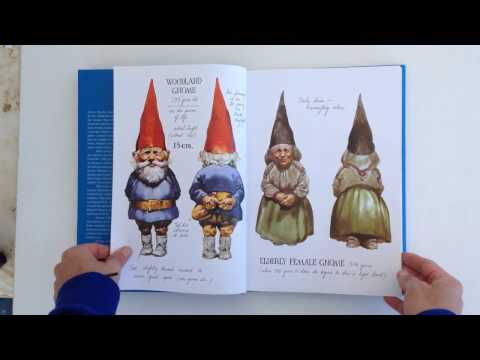

3 Garden Gnomes Get Their Own Book

While Snow White may have brought gnomes back into the public consciousness, it would take another 39 years before things really blew up. In 1976, Dutch author Wil Nguyen and illustrator Rien Poortvliet teamed up on a bombshell book simply called Gnomes. That may not sound like a groundbreaking work of literature to you, but in the gardening community, it was catnip. The two Dutch creators used the book to dive into the depths of supposed gnome history. They outlined the backstories and myths of all kinds of gnomes. There was no shortage of material, either. Nguyen went all the way back to our centuries-old long-dead pal Paracelsus. The insightful author cited pygmy lore, dwarf influences, and all other past garden guardians. Poortvliet’s illustrations really sealed the deal. The detailed, colorful pictures made the book into the first-ever encyclopedia of gnome history. It was complex and intricate, and gnome collectors loved it immediately. It was even made into a movie in 1980. Gardeners and homeowners quickly embraced the gnomes’ ancestral tales. They began collecting the critters en masse. The book proved so popular that it landed on The New York Times bestseller list and stayed there for more than a year. What had once been a niche interest crossed quickly into mainstream culture. And from there, lawn gnomes’ fate in modern society was sealed![8]

2 Brands Embrace Gnomes as Pop Culture Catches Up

For centuries, lawn gnomes and their predecessors had a purpose. Even if the efficacy of their help may have been suspect, the statues (and those real-life hermits!) were said to protect a family’s garden from evil spirits and aggressive creatures. But by the time gnomes hit it big in America in the late 20th century, the idea of protecting one’s garden from ghostly beings was far more myth than fact. Still, the gnomes’ lovable look and the popularity of Nguyen and Poortvliet’s book meant the public was focused on them. So the business world pounced! Expedia used the garden gnome to its advantage in the most high-profile way to date when they introduced Travelocity’s memorable mascot. The Travelocity gnome was a mainstay on television commercials with that group for years. More than anything else in the modern era, it solidified the gnome as a strange part of pop culture. Shrewd TV writers also picked up on the goofy trend. One particularly memorable King of the Hill episode poked fun at gnome lovers with a funny premise centered on one of the lawn loungers. True believers stayed strong, though. Around the country, gnome-spotting trips popped up. Walkers would wade through nice neighborhoods and peer into yards while yearning to see certain gnomes. Today, gnome-spotting even takes place in far-flung locales like Poland, proving it’s not just an American adventure. We wonder what neighboring Germany’s gnome factory pioneer Philip Griebel might say about these modern-day lawn looky-loos…[9]

1 Free the Gnomes?

Gnomes are part of the zeitgeist now. So much so, in fact, that nefarious teens and suspect lawn care activists have started swiping them! In 2015, the college town of Boulder, Colorado, was plagued with a truly terrifying gnome-napping spree. A suspicious organization calling itself the Gnome Liberation Front went crazy kidnapping garden gnomes. The organization would then hold the gnomes for ransom. In some cases, they sent pictures of the figurines to the gnome’s owners and stated they would never free them. Homeowners balked at the thefts. Police were technically moved to solve them; stealing is a crime, after all. But the mildly amusing way these gnomes went missing from gardens was understandably a pretty low priority for local cops. Colorado wasn’t the only site of these gnome nappings, though. Around the same time, a series of lawn gnome thefts broke out across the United Kingdom. Gnomes began to disappear from yards all over the country. Some people sympathetic to the thieves claimed the little statues had finally been freed from their dull life stuck in peoples’ gardens. Those in on the joke praised the Gnome Liberation Front’s foresight in advocating for lawn decoration independence. The rest of us chuckle along as people continue to embrace gnomes in weird ways. Wherever they are, something tells us Paracelsus and Philip Griebel might just be laughing too. [10]