These incredible works of art were mostly created by ancient flint tools that chipped away at the medium the ancient artists used. Their methods included gouging, drilling, and chiseling, while metal abrasives were used to refine surfaces with a smooth finish. Interestingly enough, some of the artworks were found hundreds of miles away from their original sources, possibly indicating that some form of trade existed. Although we will never understand its precise meaning, use, or history, it is abundantly clear that continuous effort, technique, and care were involved in their creation. Portraying both real and mythical animals and people, these ancient artworks form part of the world’s history that belongs to each and every one of us.

10 Venus of Brassempouy (23,000 BC)

A singular example of prehistoric art, the Venus of Brassempouy, is the remaining remnant of an ivory sculpture (fractured in ancient times) that was uncovered in Brassempouy in 1892, in the southwest of France. The Venus of Brassempouy—consisting of the remaining neck and head of the original sculpture—was crafted from mammoth ivory. It is approximately 3.5 centimeters (1.4 inches) high, 1.9 centimeters (0.75 inches) wide, and 2.2 centimeters (0.86 inches) deep. Unlike all other venuses discovered throughout Europe to date, this unique sculpture contains distinct facial features such as a nose, eyes, a browline, and forehead—but no mouth. On the top and sides of the sculpture’s head, representations of braided hair or possibly even a headdress have been incised. The incredible facial features make this a remarkable piece of art, even though we may never know how the rest of the body appeared or what ultimately happened to it. This Stone Age sculpture, dated to about 23,000 BC, is one of only a few that features detailed representations of the human face and could possibly be the oldest one in existence.[1]

9 Moravia Lion Head (24,000 BC)

Shortly after the digging at the Dolni Vestonice archaeological site in the Czech Republic began in 1924, the site’s importance became evident. In addition to being the site of several prehistoric burials, hundreds of fired clay and ceramic relics were unearthed. One of these was the 26,000-year-old Moravia Lion Head. Formed from fired clay, the Lion Head is 4.5 centimeters (1.75 inches) wide, 2.8 centimeters (1.1 inches) high, and 1.5 centimeters (0.6 inches) deep. Its eyes, ears, and snout were modeled with incredible detail. Whether it’s a lion or lioness can’t be determined as the lions of the Ice Age didn’t have manes. Holes in one of its eyes and above one ear could possibly represent wounds. The findings gave scientists insights into the importance of carnivores in the daily lives of the ancient inhabitants of the area. Although the acquisition of animal hides may have been their main reason for hunting carnivores, other body parts, such as bones, were used to create weapons and tools. In addition, fox and wolf teeth were used to make a variety of personal ornaments, including jewelry.[2]

8 Water Bird in Flight (28,000 BC)

The Water Bird in Flight, chiseled from mammoth ivory, was uncovered in the famous Hohle Fels Cave in the southwest of Germany. It is just one of several flawlessly exquisite representations of animal designs. It’s around 30,000 years old and measures 4.7 centimeters (1.85 inches) from the tip of its beak to its rear tailpiece. The tiny sculpture was discovered in two separate parts at the archaeological site—close to the town of Schelklingen in 2002. Relics like this one show us that animals were not only seen as forms of meat, leather, or horn in the imaginations of early human beings but that they also might have been viewed as promises or messengers. Although it is hard to determine for certain which specific hominid species created this particular sculpture, it is widely believed that the artists were modern humans (Homo sapiens).[3]

7 The Vogelhead Horse (31,000 BC)

The Vogelherd Cave is located on the eastern side of the Swabian Jura in southwest Germany. After the discovery of the Upper Paleolithic Vogelherd figurines in 1931—attributed to the Aurignacian culture—this incredible cave received widespread scientific and public attention. The petite sculptures crafted from mammoth ivory are some of the longest surviving undisputed works of art in the world. Among its most famous is the 33,000-year-old carving of a horse, the oldest sculpture of a horse in the world, which may have been used as a totem or pendant. Its features were worn down by frequent human handling, but it remains extraordinarily shaped, beautifully proportioned, and strikingly expressive. It is typically assumed to be a stallion with an assertive or imposing bearing due to its contoured neck. Unfortunately, only its head was completely preserved. As the external ivory layers have a tendency to flake, the width of the sculpture was significantly decreased, and its legs were destroyed. The sculpture also features numerous engraved symbols on the nape of the head as well as on its back and the left side of its chest, the significance of which may never be understood or known.[4]

6 The Tolbaga Bear Head (33,000 BC)

Apart from Israel, Siberia is the only area in Asia where Pleistocene art has historically captivated a satisfactory amount of attention, albeit limited. Compelling examples of paleoart have been identified at over 20 individual archaeological sites so far. While a lot of the artwork can be contributed to the Pleistocene era, most of it belongs to the Upper Paleolithic era. The archaeological site of Tolbaga is near the bank of the Khilok River in Siberia and was uncovered in the 1970s by the well-known Soviet archaeologist and historian Alexey Pavlovich Okladnikov. The intricately carved head of an animal—commonly thought to be the head of a bear—chiseled from the second vertebra of the now-extinct woolen rhinoceros—was one of the site’s most important discoveries. Microscopic examination of the tool marks found on the sculpture managed to prove that it was etched and chiseled with a variety of different stone tools. Although the outcome of the sculpture on the artist’s side certainly took a lot of time and effort, it remains incredibly detailed and contains remarkably natural features.[5]

5 Woolly Mammoth Figurine (33,000 BC)

In 2007, the first intact woolly mammoth sculpture was recovered by archaeologists from the University of Tübingen from the Swabian Jura in Germany. It is widely acknowledged that the find, which included several other figurines, was created by the first modern humans at least 35,000 years ago. Not only was the find rare due to the intact state of the mammoth, but it is also believed to be the oldest ivory sculpture discovered to date. The woolly mammoth sculpture itself is quite small, measuring only 3.7 centimeters (1.5 inches) in length and weighing just 7.5 grams (0.25 ounces). However, it also displays masterfully detailed engravings, complete with a slim shape, pointy tail, strong legs, and a beautifully arched trunk that makes it truly unique. The mini-sculpture is adorned with short lacerations, and a crosshatch sequence is shown on the soles of its feet. Collectively, a total of five ivory mammoth sculptures from the Upper Paleolithic era were discovered at the Vogelherd Cave archaeological site, made famous by the Tübingen archaeologist Gustav Reik, during its first excavation in 1931.[6]

4 Venus of Hohle Fels (38,000 BC)

Sculpted during the Aurignacian culture of the Stone Age, the modest ivory sculpture of a feminine figure widely recognized as the Venus of Hohle Fels was uncovered during archaeological digs in 2008 at the previously mentioned Hohle Fels Cave in southwest Germany. It dates back to between 38,000-and 33,000 BC, officially making it the oldest among all the known Venus figurines and the oldest indisputable example of figurativism known to archaeology. The Venus of Hohle Fels has a number of singular characteristics that are standard fare when looking at later female figurines, like the Venus of Willendorf. Its outrageous age, however, shines a spotlight on the early history of Upper Paleolithic art, proving that the Aurignacian culture was much more sophisticated than previously thought. A large number of other equally important samples of portable art were also located in the vicinity of the Hohlenstein Mountain, but none of them had their own exhibition. The tiny figurine was one of the highlights of the Ice Age Art and Culture exhibition held in Stuttgart between 2009 and 2010.[7]

3 Lion Man of the Hohlenstein Stadel (38,000 BC)

The Lion Man of Hohlenstein Stadel is the world’s oldest anthropomorphous figurine. Discovered in 1939 by archaeologist Robert Wetzel, the magnificent sculpture was unearthed within the Hohlenstein Stadel in Germany, a system of caves that continues to produce important archaeological and historically significant finds. The 40,000-year-old sculpture, created with flint and stone cutting tools, is also the first artwork ever discovered in Europe that represents a male figure. The Lion Man was not found intact, and several pieces from the front of its body remain missing to this day. It measures 31 centimeters (12.2 inches). Its posture and physique seem to suggest that he is standing on the tips of his toes with his arms by his sides. The upper part of the left arm is crisscrossed with incisions that may represent tattoo designs or disfigurement. The Lion Man was uncovered with plenty of other artifacts but continues to stand out as a truly remarkable example of prehistoric human art from the Stone Age.[8]

2 Venus of Tan-Tan (200,000–500,000 BC)

The Tan-Tan Venus was discovered during an excavation on the northern edge of the Draa River by state archaeologist Lutz Fiedler from Germany. The sculpture was located between the two undisturbed soil layers: the lower layer consisting of objects and sediment from the Early Acheulian era (around 500 000 BC) and the upper layer from the Middle Acheulian era (about 200,000 BC). Exactly in line with its excavation site, the Venus of Tan-Tan dates back to between 200,000-500,000 BC, placing it on the same timeline as the Golan Venus of Berekhat Ram and effectively dating it as the oldest art ever found in Africa. The dating also effectively discounts Homo neanderthalensis as its creators and places the artwork firmly in front of the more primitive Homo erectus. Created from metamorphosed quartzite, the figurine is approximately 6 centimeters (2.5 inches) long, 2.6 centimeters (1 inch) wide, and 1.2 centimeters (0.5 inches) deep, weighing around 10 grams (0.3 ounces). Twenty tiny specks of a vibrant red waxy substance, recognized as iron and manganese, were discovered on its surface, the subject of which is still being hotly debated as it is not 100% clear if this was some form of ochre paint. As with its equally controversial Golan sister, the Venus of Berekhat Ram, its anthropomorphous design is implied by particular ridges intricately carved into the figurine. Many of these markings have been attributed to nature, while others have been confirmed to be the result of the artifact being struck.[9]

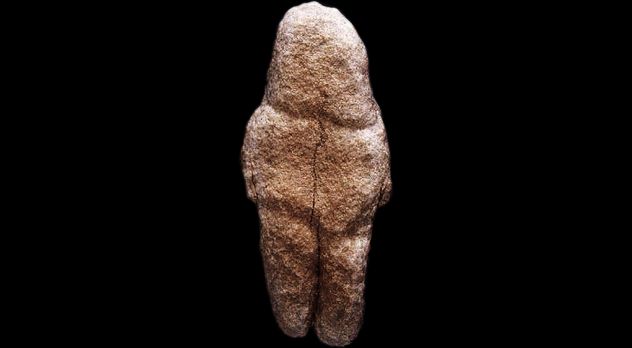

1 The Venus of Berekhat Ram (233,000 and 800,000 BC)

Our final item on the list, although highly controversial, has managed to earn a strong case for its legitimacy. The Venus of Berekhat Ram was uncovered in the Golan Heights in Israel. The object was found between two distinct layers of volcanic sediment and stone and is believed to be between 233,000 and 800,000 years old. Quite a few historians have come to believe that the relic was adapted to depict a feminine human figure, classifying it as a probable relic made by Homo erectus in the early Middle Paleolithic era. Most of the debate surrounding the find was sidelined after a microscopic analysis by Alexander Marshack clearly indicated that human interference was involved in the object’s shaping. It is widely believed that the figurine was already somewhat humanoid in appearance when it was discovered and that it was then shaped and polished with early human tools. Its base provides evidence that it was chiseled flat to enable the sculpture to stand upright. The case for the artifact was further reinforced by comparable findings in the neighboring regions, such as the Tan Tan Venus of Morrocco. For the time being, it has been concluded that the two figures may have been used for ritualistic or ceremonial purposes and that they might, in fact, be real.[10]