Today, hundreds of different sign languages are recognized all over the world. More than 70 million people use them regularly. Just like spoken languages, sign languages reflect the unique vocabularies and cultures of various nations. Deaf people have earned the respect of those around them, too. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities made sure to demand governments worldwide treat sign languages as equal to spoken languages in official communications. The UN also decreed September 23 as the International Day of Sign Languages. Things haven’t always been so easy for the deaf community, though. In fact, the development of sign language has gone through all sorts of stops and starts. Discrimination against deaf people was rampant for centuries. Linguists and politicians misunderstood and dismissed the value of sign language. But over time, those misconceptions were corrected. Here are ten surprising and enlightening facts about how sign language developed across human history.

10 Sign Language With Socrates and the Ancient Greeks

Plato wrote Cratylus more than two millennia ago. Even then, the topic of deafness was front of mind. The fifth-century BC tale recounts a conversation between Socrates and two other people. In it, the three debate the importance of names and words. At one point, Socrates explains the importance of making “signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body.” The philosopher uses the example of a horse to illustrate his point, pantomiming the animal’s movements to articulate it without speaking. Watch this video on YouTube Today, historians point to that passage as a sign that the ancient Greeks employed an early form of sign language. The communication patterns weren’t seamless, though. Other research indicates the Greeks believed it was impossible to educate deaf people. Thus, for centuries, it wasn’t even attempted. Even otherwise intelligent philosophers thought little of deaf people at the time. Aristotle once famously said deaf people could not learn, as they were “senseless and incapable of reason.” Thankfully, not everybody felt that way. Still, it would take centuries for sign language to develop and change to come.[1]

9 Sign Language Spreads Among Native American Tribes

Today, there are more than three dozen American Indian Sign Languages reflecting the communication patterns of different tribes. Those non-verbal languages have been around for a very long time. Europeans first documented “hand talk” among Native Americans in 1542. Some historians argued native signers used their hands only to communicate with the first Europeans who landed in America. But experts now agree hand signals were in use long before that. Watch this video on YouTube The most well-known AISL is Plains Indian Sign Language. Deaf people were well versed in it, but the signals were also used elsewhere. Hunters keen on keeping quiet around prey used the signals to communicate. Native peoples who traveled long distances to trade with other tribes talked through the signs too. Famous Americans were the beneficiaries of this language, as well. When Lewis & Clark traveled through the American West, their expedition communicated through the Plains sign system. Different Indigenous groups spoke different languages along the way, but sign language provided a common means of interaction. But now, sadly, PISL is on the decline. The Oklahoma Museum of Natural History considers it an “endangered” language. Few fluent signers are alive today, but reservation leaders are hopeful the system could still see a resurgence.[2]

8 Europeans Start to Evolve on Deafness

By the 16th century, European scholars had finally moved past ancient Greek views on deaf people. One person in particular impacted that the most: Dutch scholar and writer Rudolf Agricola. In 1521, he published De Inventione Dialectica (On Dialectical Invention). Agricola argued that deaf people were entirely capable of learning a language. An Italian doctor named Girolamo Cardano was particularly moved by Agricola’s work. That’s because Cardano’s own son was deaf. So the doctor began to teach the boy hand signals to correspond to Italian words. The lessons proved effective in teaching the boy to communicate in his own way. And the impact went far beyond that too. In 1575, Cardano published his own book about deafness. In it, he highlighted reading and writing styles to teach deaf people and emphasized their innate intellect. By then, more scholars were becoming wise to the capabilities of sign language. At the end of the 15th century, a German doctor named Solomon Alberti published a landmark book on deaf culture and language acquisition. He argued deaf people could read both words and lips. He also doubled down on the intelligence inherent among deaf persons. Alberti’s claim that they were able to acquire a language and become educated opened the floodgates. By the end of the 16th century, it was widely known that deaf people could acquire language skills and develop their own corresponding hand signals to communicate.[3]

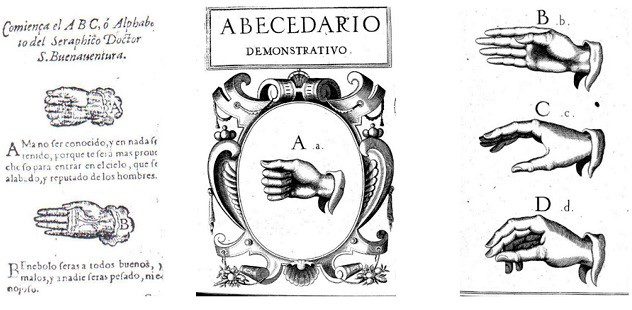

7 The Monk Who Was Determined to Move Hand Signing Forward

While Agricola, Cardano, and Alberti were hard at work on scholarly pursuits related to deafness, monks on the continent were simultaneously focused on more pressing tasks. Chief among those were hand-signing and fingerspelling. Even though many of the monks who studied and developed these techniques weren’t deaf, they had taken vows of silence for their faith. Thus, communicating with their hands became critically important. Some monks were believed to have developed intricate hand signals as early as the eighth century. But the 1500s proved to be the key time for those non-verbal cues to spill over into the rest of the world. These pious people started to realize the potential impact of their sign language. So they started teaching hand signals and fingerspelling to deaf children. One Spanish monk, Fray Melchor de Yebra, went even further. In 1593, de Yebra published the first book of images and diagrams showing how to fingerspell the alphabet. The monk hoped to use the book to attract deaf people to Catholicism. He also wanted to give priests the ability to communicate with adherents on their deathbeds who may have lost the ability to speak in their final moments. The diagrams’ impact went far beyond those sacred motives, though. By 1620, a teacher of deaf children named Juan Pablo Bonet edited and re-purposed the diagrams to reach a wider audience. Deaf children began learning to fingerspell and sign en masse. Suddenly, a standardized form of non-verbal language began to flourish.[4]

6 Deaf Servants Find Success in the Ottoman Empire

While sign language was slowly being standardized across western Europe, rulers elsewhere were already aware of the potential of this non-verbal communication. Sultans in the Ottoman Empire would hire deaf servants specifically because of their ability to communicate without speaking. Their hand languages were used for political reasons within the courts and at elite gatherings. The signs were complex and subtle. In other words, they were perfect for scheming sultans worried about leaking private information about the empire. Watch this video on YouTube Concerned with secrecy and security, the rulers also came to learn sign language. European travelers were amazed at how Ottoman elites used sign language. One 17th-century historian named Sir Paul Rycaut marveled at how sultans “perfect[ed] themselves in the language of the Mutes.” In a 1665 book about the empire, he noted there were at least 100 deaf people working as servants in the high court. Political leaders loved the secrecy brought on by the intricate signs. In quiet seclusion, sultans could “speak” with their deaf charges while behind a curtain or around a corner. All the while, they never worried an unintended audience had overheard sensitive information. While the Greeks and others had long seen deafness as a hindrance, the Ottomans viewed the trait as a blessing in disguise.[5]

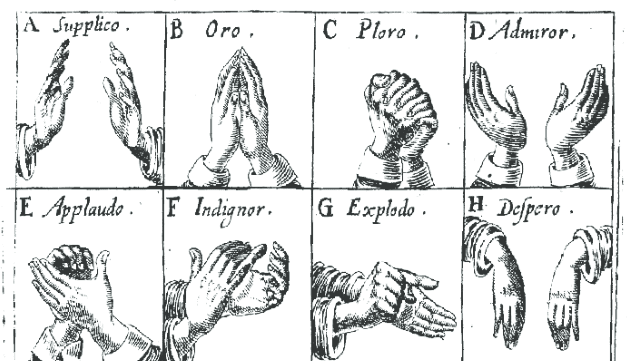

5 Sign Language Becomes Commonplace in England

The 1593 fingerspelling tract from de Yebra was a watershed moment for deaf people. And 51 years later, non-verbal communication took another massive step forward. In 1644, an English doctor named John Bulwer published Chirologia, or, The naturall language of the hand. In the book, Bulwer analyzed non-verbal ways of speaking. He argued the hand “speaks all languages” regardless of the “formal differences” of spoken words. Bulwer also offered a list of universal hand gestures. These included grabbing the chest to show sadness, waving the finger to show disapproval, and using the middle finger to “chastise men.” But there was so much more to the book than flipping the bird. Bulwer discussed the importance of a finger alphabet and a non-verbal number system. And he argued for the streamlining of a standard way to communicate by hand. In the book, Bulwer shared intricate diagrams of alphabet letters and hand gestures. Though rudimentary compared to today’s sign language output, many of the diagrams in Chirologia have a striking resemblance to modern methods of expression. The book’s popularity pushed forward the use of a consistent form of hand signals in Europe. By the mid-17th century, sign language was gaining momentum across the continent.[6]

4 A French Priest Steps Up to Standardize Signs

Inspired by Bulwer’s work, a Catholic priest from France named Charles-Michel de l’Épée decided to standardize sign language. The priest drew on an old non-verbal language used in France known today as “Old French Sign Language.” Taking Bulwer’s idea and applying it to French, de l’Épée created a clear system of signs meant to express common ideas. He also further standardized the alphabet spelling system used by deaf people around Europe. His work truly lasted the test of time. Linguists now point to de l’Épée’s standardization as the birth of the French and American sign languages we know today. Not content to stop there, the priest also opened an educational institution for deaf people. That school still exists as the National Institute of Young Deaf of Paris. For good measure, he added a dictionary to the mix. While the word list was completed after de l’Épée’s death, his additions in life were critical. For his persistent pioneering work, the priest is now known as the “Father of the Deaf.” And thankfully, de l’Épée wasn’t the only one keen on deaf advocacy. In 1779, a fellow Frenchman named Pierre Desloge published a book defending the use of sign language as the right way to educate people who could not hear. The Parisian bookbinder knew of what he was writing, too: he just so happened to be deaf. Today, historians wonder whether Desloge’s work may be the first book mass-produced by a deaf author.[7]

3 The First Beginnings of American Sign Language

The impact of France’s de l’Épée pushed other scholars ahead in their work. American Sign Language, known today as ASL, came about in the early 1800s following the success of its French forebear. A minister named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet had been spending his free time teaching the alphabet to his deaf neighbor, Alice Cogswell. Inspired by her progress, he wanted to provide an outlet for more deaf children. So in 1817, he founded the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. Watch this video on YouTube As for ASL, Gallaudet’s new institution was one of several that took the French model from de l’Épée and altered it for English speakers. With scholars like Gallaudet working toward an end goal, the American version standardized quickly. Soon, it ended up being wholly unique from its French counterpart. Today, ASL has defined and separated language rules and grammar structures. By 1830, ASL had already become the favored signing method across America. And much like de l’Épée in France, Gallaudet’s work on behalf of the American deaf community would not be forgotten. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating the National Deaf-Mute College in Washington, D.C. The school was a landmark institution for deaf students at the time. Today, its reputation continues to be stellar as the world’s only accredited university for students who are deaf. Its name has changed, though: it is now known as Gallaudet University.[8]

2 Troubling Talk Amid American Sign Language Opponents

As ASL was standardized, some educators worried about the cultural impact of sign language. As the 19th century went on, a vigorous debate kicked up. On one side were manualists like Gallaudet, who emphasized the importance of sign language. On the other side were oralists, who believed deaf people should not be taught to sign but instead only learn to read lips and speech. Watch this video on YouTube Oralism got a big boost in 1880 when the International Congress of Educators of the Deaf was held in Milan, Italy. Organizers of that conference excluded deaf teachers from attending. Alone and without debate, the oralists there argued that lip-reading and speaking were superior to signing in order for deaf students to communicate. Today, of course, we know there is nothing wrong with lip reading. People who are deaf read lips to communicate. But it often works better for those who become deaf later in life rather than those who are born without hearing. The 1880 convention didn’t see it this way, though, and the oralists in attendance thrived. For years after the convention, deaf schools around the world shifted to oralist methods of teaching students. Many also banned deaf teachers with the move to oralism. In turn, deaf students were less able to relate to those teaching them. One of the most staunch proponents of oralism was Alexander Graham Bell. The influential inventor of the telephone spent years publicly debating Gallaudet’s manualist supporters. Bell’s wife and mother were both deaf, so he did have experience in the community. But his arguments were troubling, even for the time. He believed deafness was a threat to American identity. At one point, he even argued deaf people shouldn’t be allowed to marry or have children. Of course, that was an interesting position to take, considering his family situation. Nevertheless, Bell argued for eliminating all sign language and wanted to ban deaf teachers from schools. Today, Bell’s oralist side has now solidly lost the debate. But the inventor’s years of public commentary on the “defective” nature of deaf people has stuck. Even now, no matter their capabilities, people who are deaf must navigate a noticeable negative cultural stigma. [9]

1 Sign Language (Finally!) Flourishes in the Modern Era

By the 1960s, American Sign Language was well established. Linguists had shied away from studying it, though. Oralists were still prominent in the academic world, and manualists interested in ASL were cast out. That started to change in the 1960s when Gallaudet professor William Stokoe began researching the linguistics of signing. He applied for a grant from the National Science Foundation to fund his studies. Despite intense criticism from oralist scholars, Stokoe persisted. The NSF backed his grant, and the product was memorable. Watch this video on YouTube In 1965, Stokoe published the Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. The book almost immediately revamped deaf education in America. Teachers began embracing manualist theory, and ASL flourished. Years after that work, another Gallaudet professor built on Stokoe’s legacy. In 2006, professor Clayton Valli published The Gallaudet Dictionary of American Sign Language. Today, it is one of the most widely used reference books on ASL. It contains thousands of illustrations, etymological sources, and a detailed index. Today, sign language has spread well beyond its French and American roots. In the Far East, millions of people have learned the non-verbal language. In China, the government took a full-scale approach to standardize several sign language dialects through the 2010s. In 2018, the new standards for Chinese Sign Language were released in the country. The Chinese standardization now contains more than 5,000 common words corresponding to commonly used characters of the country’s spoken language.[10]