Once they crossed the lines on Nov. 8, the German delegates were not driven directly to the railway car where the armistice talks were to be held. Rather, the French gave them a 10-hour “scenic tour” that showed incredible damage to the French countryside after four years of war. The delegates were then ushered into a rail car in the forest of Compiegne to begin the talks that lasted three days. After being informed that Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated on Nov. 10, the German delegates received an un-coded message from general-in-chief Hindenburg to accept whatever terms they could get — and quickly — because of rioting and increasing unrest at home. The picture shows just a small portion of the devastation in northern France.

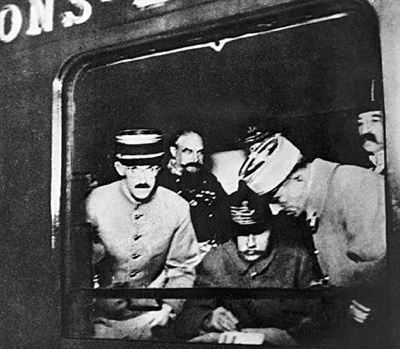

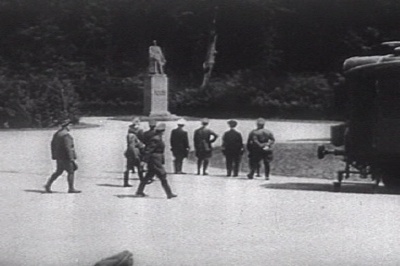

The Germans and Allies signed the armistice just after 5 a.m. Paris time. Only one photograph seems to exist of the actual signing, unlike, say, the surrender of France in 1940 or the surrender of Japan in 1945. The photo above appears to have been shot through a window; I think that’s Matthias Erzberger, the chief German negotiator, at far right. This other photo shows the Allied representatives shortly after the signing; Marshal Foch stands second from right.

The rail carriage (car) and armistice spot later became a national monument. Almost 22 years later, in June 1940, Hitler made the French surrender in that very rail car. Before the Allies liberated France in 1944, Hitler ordered the monument dynamited and the following year ordered the carriage itself destroyed, to prevent a possible second German armistice or surrender from being signed in that same car. Here’s how the site looks today: http://pierreswesternfront.punt.nl/?r=1&id=435051

The armistice was signed just after 5 a.m. (Paris time) the morning of Nov. 11. The fighting was to officially end at 11 a.m. The German delegation had requested an immediate cease-fire, but the Allies set a six-hour deadline so that all commanders could get the word. When they heard the news, some commanders had their men stand down. Why fight for piece of ground that you could simply walk over a few hours later? But others continued to attack — especially some American commanders — who saw chances for “glory” or promotion slipping away, or because they thought the Germans needed to be flat-out beaten. Several thousand men on both sides were killed or wounded in the final six hours of the war. For example, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission recorded 863 British and Commonwealth deaths on Nov. 11. The picture shows German troops under attack in the final weeks of the war.

One American artillery captain kept his battery firing at the Germans until just minutes before 11 a.m., because he believed the armistice was premature and the Germans needed to be truly beaten, not just defeated. His name? Capt. Harry S. Truman. Some historians draw a straight line from Truman’s actions on 11/11/1918 and his decision to use the atomic bombs.

In a freak coincidence, the British Army started and ended the war at Mons. Some of the first British soldiers killed in the Great War died at Mons in August 1914, when the five divisions of the BEF fought their first battle. More than four years later, the British returned to Mons, and some of the very last Commonwealth soldiers killed in the Great War died there on November 11, 1918. Scroll down this page of the St. Symphorien Military Cemetery at Mons, which has the graves of the first and last British soldiers killed at Mons.

Many men wounded on November 11 succumbed to injuries after the 11th hour. Many more endured years of pain and suffering over physical wounds that couldn’t quite heal right or could never be healed. One of the most horrifying, a Commonwealth soldier named Thomas, was gravely wounded on Nov. 6, just before negotiations started, and was still alive AND conscious when the armistice took effect. Whatever hit him in the face literally tore away the lower parts of his face — nose, mouth, jaw. Amazingly, he survived. After years of surgical reconstruction, Thomas finally had something approaching a normal looking face in August 1922.

Matthias Erzberger, Germany’s lead negotiator at the Armistice, initially supported the war until 1917. By then, the static and incredibly bloody lines in France convinced him that Germany should negotiate a peace. Prince Max Von Baden picked Erzberger to lead the negotiations because Erzberger was a civilian and known opponent of the war. After the fighting ended, Erzberger joined the newly formed government and endorsed the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which many hard-core Germans held in contempt. For his role in the “stab in the back” (see #2), Erzberger was forced from office in 1920 and murdered in 1921.

Historians generally (but not totally) list a German soldier by the name of Lt. Tomas with being the final German casualty. He was killed after the 11th hour by an American unit that apparently hadn’t received word of the cease-fire. The final German killed before the 11th hour is not known. According to generally accepted records, the last British, Canadian, French and American men killed were the following: British soldier George Edwin Ellison died around 9:30 a.m. while scouting around Mons. French soldier Augustin Trébuchon was killed at 10:45 a.m. while spreading the news that they would get hot soup after the 11th hour. Canadian soldier George Lawrence Price died two minutes before the 11th hour, just north of Mons. The last man believed killed in the Great War was American soldier Henry Gunther, 60 seconds before the 11th hour. German soldiers were shouting and waving at Gunther and the others to go back. The photo above is of Gunther.

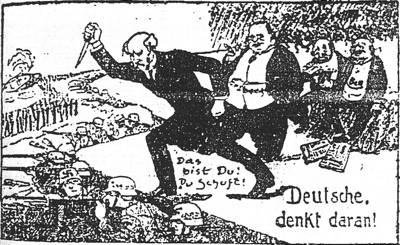

Most accounts of the end of World War I and the origins of World War II contain some discussion of the “stab in the back,” the claim that the German army had not been defeated but was betrayed by the civilian leadership. This wasn’t merely a Nazi propaganda line, either – many Germans heading home from France, Belgium, Romania, Italy, Russia, etc. really did believe it. Never mind the facts. The military leaders had told the Kaiser that the army and navy would no longer support him; naval mutineers had refused to fight any more; the army high command had sought the armistice before Allied armies hit German soil; and the home front was literally starving and rioting. Nevertheless, the legend of the “stab in the back” became darn near holy writ. So, while the Nazis didn’t create the “stab in the back” legend, they certainly exploited it to devastating effect.

Both AEF commander Gen. Pershing and Allied supreme commander Foch of France were unhappy with the nature of the armistice and subsequent Versailles peace treaty. Pershing believed that it was a grave mistake to let the Germans simply lay down their arms without actually being beaten. (They were defeated, yes, but not beaten.) He correctly predicted that because they did not make the Germans beg for peace on their knees inside a ruined Germany, the Allies would soon be fighting them again. Foch was even more prescient. Upon reading the Versailles treaty in 1919, Foch was heard exclaiming, “This isn’t a peace. It’s a cease-fire for 20 years!” Twenty years and two months later, England and France declared war on Germany.