You would think that the descendants of revolutionaries would take more care in drafting their own laws. You would be wrong. Some US politicians have passed bills and acts that are morally wrong, infringe on citizens’ rights, or impose their own reprehensible beliefs on an entire country.

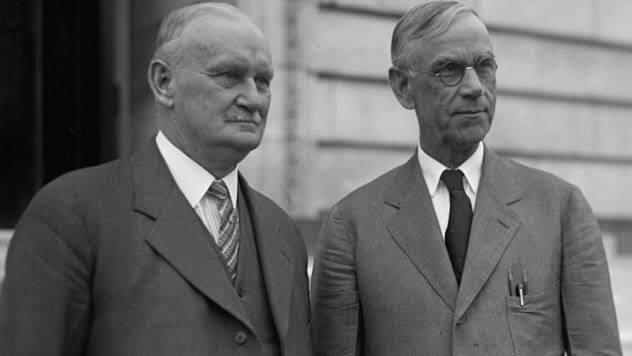

10 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (officially known as the Tariff Act of 1930) is one of many nationalistic laws passed by the United States. Ostensibly, it was created to help protect American businesses and farmers from economic turmoil by raising tariffs on over 20,000 items by as much as 20 percent. In desperation, more than 1,000 economists signed a petition to persuade then-President Herbert Hoover to veto the bill. But he wouldn’t, as promising to raise agricultural tariffs had been an important part of his campaign. The stock market had just crashed, and the world was taking its first steps into what would become known as the Great Depression. Instead of insulating the US, like its proponents had hoped it would, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act kicked the country off a cliff along with the rest of the world. (However, the harm done to trade with other countries was perhaps its biggest impact.) Thomas Lamont, a partner at J.P. Morgan, later said of the act: “[It] intensified nationalism all over the world.”[1] In fact, some people have argued that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act may have contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler because it deepened the Great Depression.

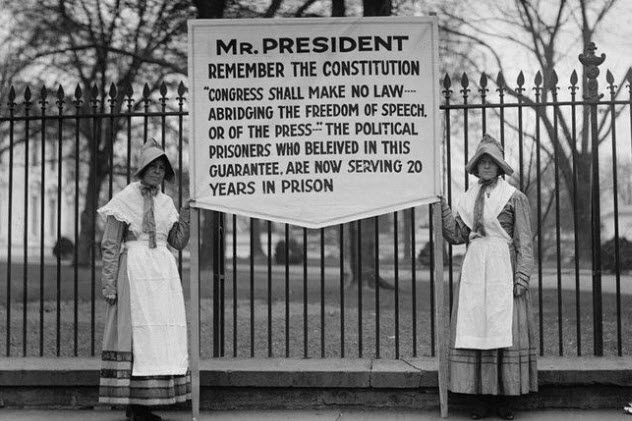

9 Espionage Act And Sedition Act

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the related Sedition Act of 1918 were passed shortly after the United States’ entry into World War I. The Espionage Act was created as a compromise between the US, with its relatively tolerant opinion on freedom of speech, and Great Britain, which had passed a massive ban on speech pertaining to national secrets a few years earlier. In short, the act made it a crime for a person to send information that would compromise the country’s war effort or aid its enemies. In 1918, the Sedition Act expanded the range of the Espionage Act. Under the Sedition Act, it was a crime to make false claims that hindered the war effort or to disrupt the manufacture of items necessary for the war. It was even illegal to insult the US government, the flag, the Constitution, or the military. Defending these actions as legal was also a crime.[2] During the first Red Scare in the postwar years, these two acts were used to an extreme, mainly by A. Mitchell Palmer, the US attorney general, and his right-hand man, J. Edgar Hoover. Only a few years later, the Sedition Act was repealed, though many parts of the Espionage Act remain law today.

8 Alien Registration Act Of 1940 (aka Smith Act)

As the United States’ entry into World War II looked increasingly likely, US lawmakers tried to chop off the head of the rebellious menace they felt could help take the country down from within. Their solution was the Alien Registration Act of 1940, which made it a crime to either advocate for the overthrow of the government or be a member of a group whose main goal was to topple the government. In addition, all aliens (noncitizens) living inside the country had to register with the government, get their fingerprints taken and filed, keep identification papers on their persons at all times, and inform the government of their living situations each year.[3] Lastly, if an alien were to have ties, however loosely, to a “subversive organization,” he could be deported. Though it has never been repealed, the act has been amended a number of times after some of its uses were deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

7 Gulf Of Tonkin Resolution

Much like the Roman general and eventual dictator Sulla did when he first crossed the pomoerium (city limits) of Rome with his army—setting the stage for people like Julius Caesar—the Gulf Of Tonkin Resolution of 1964 has been used as precedent for many US presidents who wished to engage in armed conflict. Before the US’s entry into the Vietnam War, North Vietnamese forces had fired on two different US ships, unprovoked of course. Facing increasing criticism from his Republican opponent, President Lyndon B. Johnson sought Congressional approval for broad, far-reaching powers to protect US interests in the region. Nearly unanimously passed (only two members of the Senate objected), a bill known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution flew through Congress in 1964, giving the president the power to wage war without a formal declaration from the legislative branch.[4] It was repealed in 1971 as then-President Richard Nixon sought to escalate a conflict in Cambodia. Subsequent investigations into the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which led to the passage of the resolution, revealed that some of the information given to Congress was false, a sobering lesson and a mirror of sorts for the Iraq War.

6 Patriot Act

Passed only weeks after the attacks on September 11, 2001, the Patriot Act was ostensibly created to help the US government uncover suspected terrorists and stop them before they could carry out any attacks. However, it actually gave the government sweeping powers that enabled them to spy on virtually every American and violate people’s rights to privacy. In fact, when asked by the inspector general of the Justice Department in 2015, the FBI admitted that they could not point to a single major terrorism case which had been cracked with the aid of the Patriot Act. Instead, programs like the NSA’s phone metadata program sprang up.[5] The agency claimed that this helped it look for societal links between suspected terrorists and terrorist groups. Though a handful of governmental overreaches have been curtailed in recent years, much of these powers remain intact—which is to say nothing of the government’s international surveillance programs.

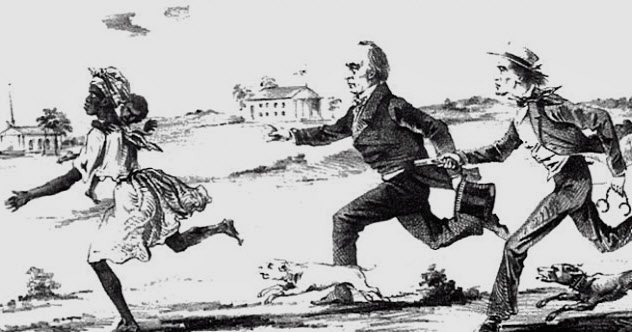

5 Fugitive Slave Act Of 1850

Beginning in the 1830s, abolitionists in the North had finally begun to coalesce into a more powerful group, frightening slave owners in the South. There was already a Fugitive Slave Act on the books, which granted local governments the power to capture runaway slaves and return them to their owners. But people in the South felt that it didn’t go far enough. They were also worried that people in the North would help to hide runaway slaves, which the Southerners couldn’t abide. So, as part of the “Compromise of 1850,” which was designed to assuage Southerner’s fears and their threats of secession, the government passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. An incredibly harsh, proslavery measure, it forced citizens to help capture runaway slaves.[6] If they refused or aided a runaway slave, they were faced with a $1,000 fine and six months in jail. In addition, the act denied slaves the right to a jury trial. After the Civil War broke out, the process of repealing the law was shelved until 1864, when Congress finally took it off the books.

4 Black Codes

The Black Codes, a collection of laws passed throughout a number of Southern states in 1865–66, can be seen as a precursor to the Jim Crow laws with which people are more familiar. Even though freedom was preferable to slavery for blacks, the situation was still fraught with constant racism. In fact, some would argue that current conditions haven’t improved as much as they could have. Under the codes, blacks were required to sign yearly labor contracts. If these onerous agreements were left unsigned, blacks could be arrested as vagrants and forced to work for free. These laws also barred blacks from serving on juries and limited their ability to travel, which mirrored legislation in place since the Revolution. President Andrew Johnson, who rose to power after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was a Southerner and a firm believer in states’ rights. He felt that the South had the right to treat blacks however they wanted as long as the blacks weren’t slaves. It wasn’t until the period of Radical Reconstruction that the treatment of blacks in the South began to improve. At that time, the Republicans essentially overruled President Johnson, passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, among other things.[7]

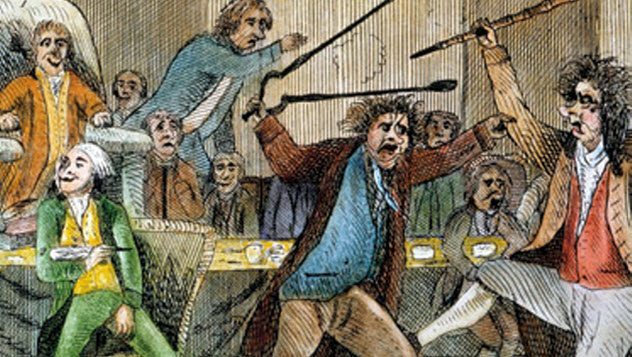

3 Alien And Sedition Acts

Shortly after the American Revolution, with the Constitution and the rights granted under it still fresh in everyone’s minds, the president and Congress decided to stomp all over it. Fearful of a French threat to the country, the US government passed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. These laws granted the government new and far-reaching powers to deport foreigners, a problem which one member of Congress described thusly: There is no need to “invite hordes of Wild Irishmen, nor the turbulent and disorderly of all the world, to come here with a basic view to distract our tranquility.”[8] (It should come as no surprise that immigrants were much more likely to support the other party.) The Alien and Sedition Acts also infringed on the First Amendment, making it a crime to publish false writings against the government. Inciting opposition to anything done by Congress or the president was also deemed to be a criminal act. Though no foreigners were deported under these laws, 10 people were convicted under the Sedition Act. Thanks to a change in Congress and the diminished threat of war, nearly all of these laws were repealed a few years later.

2 Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act is yet another reason why Andrew Jackson is the worst president in US history. A longtime advocate of what he called “Indian removal,” Jackson had fought against a number of different tribes, stealing their land and giving it to white farmers while he was an army general. When he became president, Jackson continued his crusade, signing the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830. It gave the federal government the authority to take Native American land east of the Mississippi and “give” them land west of the river. Though the law required Jackson and his forces to negotiate with the tribes without threat of violence, that part was often ignored, resulting in the “Trail of Tears” as the most noteworthy and widely known of the expulsions. For example, of the 15,000 Choctaws who were forced out of their ancestral lands, approximately 2,500 died during the resettlement. Worst of all, Jackson believed that he was implementing a “wise and humane policy” designed to save the Native American tribes from extinction.[9]

1 Public Law 503

President Franklin Roosevelt had already issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing military officials to detain anyone they felt would hinder the war effort. But he and his cabinet understood that they would need to codify it eventually. Thus began one of the most shameful periods of US history: the unlawful internment of over 127,000 innocent Japanese-American citizens in the 1940s. Based on an erroneous belief that all Japanese Americans would flock to their ancestral country if the US was invaded and the fact that the majority of them lived on the West Coast, internment camps were set up in the middle of the country. In addition, nearly two-thirds of those interned had been born and raised in America. Many of them had never even been to Japan. Though Public Law 503 was eventually challenged in the Supreme Court, it was upheld, with the Court justifying it as a wartime necessity. When the war was over, many former interns were unable to return home, with some cities even putting up signs declaring them unwelcome. It wasn’t until 1988 that Congress tried to apologize in any way, offering surviving interns $20,000 each.[10]