The Danse Macabre, French for “Dance of Death,” is an artistic and literary movement that celebrated the universality of death.[1] Emerging as the Black Death ravaged Europe, it influenced plenty of art and culture that came after it, from classical ensembles to the modern-day New Orleans jazz funerals. From Willie Stokes Jr., a man who had a casket made to look like a Cadillac, complete with blinking headlights, to more common things like cremation, humans have been extremely inventive when it comes to how they’re going to pay their respects to the dead.

10 Prehistoric Burials

Before we get around to the caskets, rituals, dances, and mortuaries we’re familiar with today, we need to look at the practice of burying the dead throughout human history. Humans have been doing so in elaborate ways for a very, very long time, with the first burials that we know about dating as far back as 100,000 years ago. Qafzeh Cave in Israel is one of the oldest burial sites we’ve found, dating back to the Middle Paleolithic period of human history.[2] Featuring the bodies of at least 27 Paleolithic individuals as well as several animals dating from different periods, this grave site was unmistakably intentional because of one prominent feature: decorations. The decorations of the skulls and other body parts were done with red ocher, and other instruments of decor were observed at the site. Two of the skeletons are almost entirely intact. The skulls had been painted with red ocher, which was most probably done as part of a religious funeral rite of some sort.

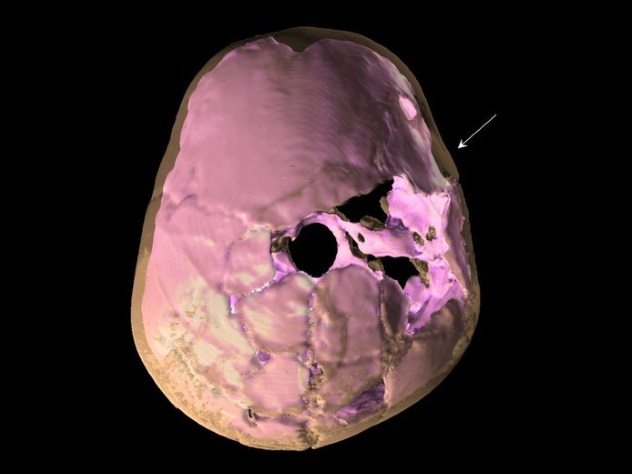

9 Tomb Of The Mutilated

These rudimentary and archaic grave designs set the stage for what would become the modern caskets of all types we find around the world today. The bodies found at the Qafzeh Cave burial site also had some other unmistakable features, most notably that all of them seemed to be the victims of violence of some sort. The Paleolithic was a rough time, between intertribal violence, familial rivalries, and the difficulty in securing food without being killed by an angry wild animal, and they seemed to have taken the funeral rites (which happened often) very seriously. Shells were found, along with a set of deer antlers, snail shells, and other such objects which were obviously used to decorate this mass grave.[3] This set the stage for another invention that would come many, many years later: the tomb. While the mass graves of prehistory were definitely decorated, they were just the basic forerunners to what would be the tomb, which is an actual structure built around the bodies, typically of families or other tight bands of people. A tomb is a built or excavated encasement, which separates it from mass graves. One of the oldest-known tombs comes from the Neolithic period, about 6,000 years ago, and was discovered in modern-day Spain. Experiments and DNA analyses of this site have uncovered that these bodies are of families, and they were buried together. It’s safe to say that funeral arrangements were a responsibility of the close family for a very long time, and those family members wanted to make more lavish structures to honor their dead.

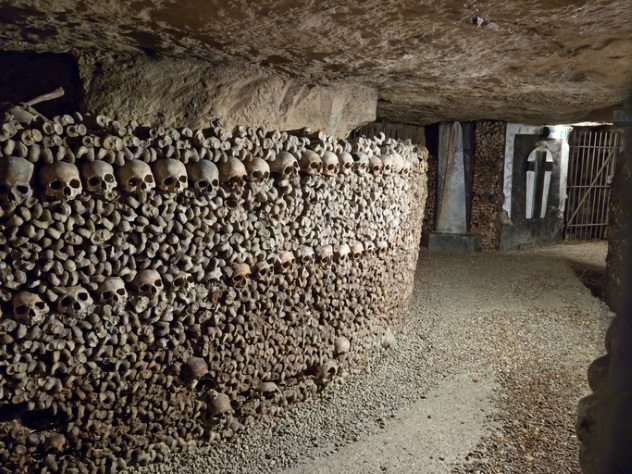

8 Among The Catacombs

From the tombs of old, it was only a matter of time before the structures built in the honor of the dead became both more intricate and more massive. Catacombs are vast, labyrinthine underground cemeteries that can house tons of bodies. These excavated structures are like whole cities of tombs underneath the ground where the living dwelled.[4] Catacombs served a whole new purpose that the graves of old simply couldn’t: They were accessible . . . but they weren’t too accessible. Throughout history, grave robbing was a real problem that people faced, with graves not only desecrated but belongings and even whole bodies being stolen. Catacombs provided accessible galleries where people could enter and pay their respects, while resting loved ones and precious belongings that needed to be hidden could literally rest in peace, even in times of constant strife. Needless to say, between sheer depth and secret, labyrinthine passages, people who buried their dead in catacombs had little to fear in the way of grave robbers and other malicious persons. But catacombs were more than just cemeteries underground; significant effort went into the art, architecture, and design of these subterranean cities of the dead. Some feature pillars which span several meters and walls made entirely from highly organized piles of bones, decorated in such a way to give a mosaic look or to add a pattern to an otherwise blank canvass of excavated earth.

7 Set Ablaze

The Vikings had a rather unique and lengthy process for honoring their dead and lost loved ones. For high-status members of Viking society, they would place the dead atop a ship and sail them off into the seas and into eternity. Often, the Vikings would set the ship ablaze before pushing it off into the water so that the flames would burn the bodies up and distribute them into the air. This was, however, reserved for only the Vikings of extremely high social status, as this was a time-consuming practice, and it would have been unthinkably grueling to have to build an entire ship, a task that took hundreds, if not thousands, of labor hours, for each and every burial. The ships weren’t always sailed off, nor were they always set ablaze, but we know that they were involved in particularly important rituals that paid respect to great warriors or leaders. The Oseberg ship is a Viking vessel found buried on land. The remains of the ship were found near Oslo, Norway, right after the discovery of a similar ship. Both were buried into hills or mounds. Carbon dating places the Oseberg ship around the early 1200s, the height of the Viking era. The ship is tremendously well-preserved, with the skeletons of two women, one in her eighties and the other in her fifties, found alongside two axes that were also extremely well-preserved.[5] The ship itself has been put out on display at the University of Oslo, along with its contents.

6 Burials Of The Black Death

During the Black Death in the 1340s and 1350s, bodies were piling up in the streets, and the dead were quickly becoming innumerable. The plague was so deadly that between 30 and 60 percent of Europeans died. Stop and think about that for a second: You’ve got ten close friends or family members when the pandemic hits; three to six of them won’t make it. The plague was a terrifying time. As we’ve seen, up until this point in history, funeral and burial rituals were often elaborate, even as far back as the Paleolithic, but once the plague came about, the dead were simply too numerous to bury and far too deadly to handle for fear of further spreading the infection. The plague quickly enveloped Europe, and soon, some bizarre strategies to deal with the disease sprung up. You’ve probably seen depictions of plague doctors dressed as birds, though this costume didn’t come about until the 1600s. As much as the bird outfits looked like the product of some macabre superstition, they were actually very sensible; the masks and overcoats protected doctors from contact with the disease. Even in the 1340s, though, they definitely knew that coming into contact with the plague victims could be fatal. The culture that sprang up during the several centuries of plague that haunted Europe could very well be seen as one giant funeral ritual. And here’s where the phrase “no man’s land” came to be: In 1348, the Bishop of London bought a property appropriately called “No-Man’s Land” for burying plague victims. Here, the dead would be stacked several bodies high without much regard to funeral rites at all and then covered with dirt so as to prevent spread of the infection.[6] When No-Man’s Land filled up, another man bought an adjacent 13-acre property for more plague burials. This was genius, and another notable feature of these properties was that they were far removed from London. The Black Death was the peak time in history where funeral rituals were less concerned with honoring the dead and more concerned with not joining them.

5 La Danse Macabre

The French phrase that’s been popularized in Western literature and art literally translates to “The Dance of Death” and has a fascinating history. As the bodies piled up throughout the plague, people came up with various ways to cope, and among them was the expression of death as a personified entity. Much art, literature, culture, and even music reflected the death that was seemingly all around the European world at the time. This all served as a sort of comforting acceptance of the universality of dying. Death is not only inevitable but also impartial, and it doesn’t care whether you’re rich or poor, a saint or a sinner; it comes for us all. This concept also served, in a time of much social stratification, as an equalizer: No matter how good you think you have it, death comes for us all. But make no mistake, La Danse Macabre was certainly more than just a tradition of interesting-looking art; it was a tradition that, in the personification of death, helped with the grieving process for those who’d lost friends and loved ones. What seem like grim, dark relics of history were actually, at the time, expressions of life and death both, much of which was intended to be comedic. Through elaborate plays, elegant paintings, sweet, soulful music, and yes, even comedy, people of the Middle Ages lived La Danse Macabre to gain mastery over the death that beset them on all sides. It gave them a sense of control, at least in mind.[7]

4 Flagellants

Another strange tradition of death that sprang up from the plague was self-flagellating, as was performed by religious sects. People would go walking through the European cities and towns beating, carving, and cutting themselves; these sects also denied themselves food and water and would starve themselves. They lived an extremely ascetic life deprived of pleasure, thinking that the plague was from God for man’s straying from Him in the pursuit of earthly pleasures.[8] In a terrifyingly uniform fashion, these masochists would waltz into a city that was plagued with death and riddled with corpses, head straight for the local church to give their prayers, and then find the town center, where they would form into a circular unit and begin their litany of self-harm and abuse. With large, knotted whips, they would beat themselves and each other in hopes of pleasing God and fending off the death that had beset the city they found themselves in. While flagellants, like ascetics, existed long before the Black Death, never had it been so popularized and practiced out in the open before. The Black Death made flagellants a household name.

3 New Orleans Jazz Funeral

The opposite of the flagellants abusing themselves and depriving themselves of all earthly pleasures are the participants in New Orleans jazz funerals. Of course, a prominent part of the jazz funeral is a procession carrying the coffin to be buried, but there’s more to it than that. These traditions of death are essentially block parties where the living celebrate the deceased with big parades and loud music. It’s not uncommon to see people dressed up in costumes dancing around the streets. Music, especially jazz, is a prominent feature of every aspect of New Orleans life; this comes from the rich traditions of La Danse Macabre and the African roots of celebration of all aspects of life, including death.[9] And these block parties are no small deals, either; some have lasted up to a week. They have horses, radio stations with DJs and loudspeakers, headdresses, and so on. But this isn’t just a vain excuse for a good time; there is a rich meaning of life after death woven into the celebration.

2 Dead Friends

On the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, there is a bizarre custom (to those in the Western world, at least) where the participants actually develop a relationship with the dead, their deceased friends and loved ones, in a festival called the Ma’nene. This tradition tells its followers to exhume the buried corpses of those they care about and treat them like living human beings. Every three years, they dig up their dead and then proceed to bathe them, clothe them, carry them around wherever they go, and generally live with them—at least for a little while.[10] The mummified cadavers are made to resemble the dead persons’ appearance in life, at least as much as possible. This highly formalized event isn’t something new; it’s been with Torajan culture for hundreds of years. While not many people practice this today, it’s referred to as the way of the ancients.

1 Death In The Space Age

It was only a matter of time before the human race and its fascination with death and the traditions surrounding it went high-tech. Enter burial in the space age. Companies are now springing up to offer you the chance to blast your loved one into the night sky, offering the concept of having them rest among the stars. In this process, the person’s remains are cremated and then sent outside of the Earth’s atmosphere for a true outer space burial tradition. This idea doesn’t come without options: You can choose if you want your loved one to enter space and then return to Earth, go into Earth orbit, orbit or land on the Moon, or even be launched into deep space.[11] Those whose ashes are orbiting the Earth could be said to be looking down upon us. But more than becoming a cremated pile of resting remains in space is offered. You can also choose to have the DNA of your loved one sent into deep space, presumably in hopes that some life-form may inherit it and that somehow, the most fundamental unit of your loved one will integrated into an alien society or perhaps will merge with other building blocks of life and start a completely new race. At present, space burials are relatively new, having started in the 1990s, so the question looms as to what will happen to them and how we will look back on them in the future. Will they be bizarre, almost superstitious practices like flagellation to ward off constant sickness and death? Or might we be onto something a bit more progressive and nuanced? Like all of the items on this list, time will tell, and as humankind progresses further into the future, so, too, will our desire to honor our loved ones with elaborate traditions. I like to write about dark stuff, the macabre, death, history, and philosophy. I’m still running Murderworkis: Horror and All Things Creepy, as well as Serial Killer Memes, Beautifully Disturbed and more. This will be shared on those pages, hopefully bringing readership.