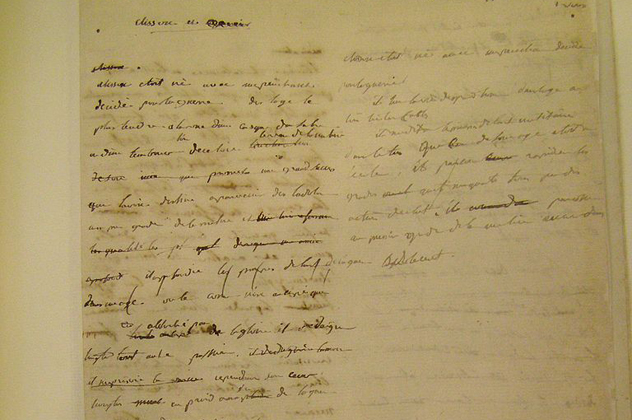

10Napoleon Wrote A Romance Novel

This story is part truth and part embellishment. In 1795, Napoleon wrote a short story (only nine pages, so not a novel) titled “Clissen et Eugenie.” Historians generally agree that it’s, in part, a reflection of the relationship he had shared with Eugenie Desiree Clary, a relationship that was ending as he wrote the story. The story itself wasn’t published while Napoleon was alive, but multiple copies were preserved in varying conditions by friends, relatives, and fans of the great man, and the full story was eventually recompiled from these various copies. Napoleon, it turns out, had always been something of a writer. He once stated that he was writing a poem about Corsica, which either was never finished or never shared. At the age of 17, he was encouraged to publish a history of Corsica which he had written, but by the time he got a bookseller interested, Napoleon—now a soldier—was called off to battle. The emperor was not only a writer, he was also his own worst critic. At the age of 17, Napoleon tried for a prize from the Academy of Lyons by writing an essay on the topic “What are the principals and institutions, by application of which mankind can be raised to the highest pitch of happiness?” Many years later, Napoleon was handed the copy of this essay that had been kept in the academy’s records; he read the first few pages, then tossed it on the nearest fire.

9In The Footsteps Of Moses

Around 1798, while in Egypt and passing through Syria, Napoleon and some of his cavalry took advantage of a quiet afternoon and the ebb tide of the Red Sea to walk across to the opposite coast on the dry sea bed, where they visited some springs called the Wells of Moses. Curiosity satisfied, the group of men returned to the Red Sea to make their way back across. By that point it had become dark, and after they began to cross, the tide started coming in. Unable to see where to go in the dark, with the water rising and obscuring the path they had earlier followed, Napoleon ordered his men to form a circle around him facing out, like spokes of a wheel. Then each man rode forward until they found themselves starting to swim, at which point they were to turn and follow the man closest that was still riding on solid footing. Soon enough, the men were following behind the riders whose horses could still touch the bottom. They all escaped from the Red Sea, drenched but unharmed. Having nearly been washed away like the pharaoh who chased Moses centuries before, Napoleon had to observe that the situation “would have furnished all the preachers of Christendom with a magnificent text against me!”

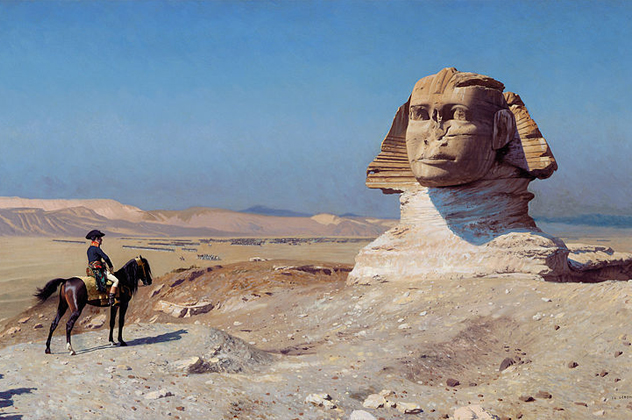

8Did He Shoot Off The Sphinx’s Nose?

One story told now is that, while Napoleon and his troops were in Egypt between 1798 and 1801, he had his men test their cannon skills by shooting at the Sphinx; this is, of course, the reason the monolith now has no nose. The story is easily refuted, as another Frenchman, Frederic Louis Norden, published an illustration of the Sphinx in 1755 that shows its nose was already missing before Napoleon was born. The tale of Napoleon shooting the Sphinx appears to have only begun to be told at the start of the 20th century. The more commonly accepted story by historians about how the Sphinx lost its nose is that, in 1380, a fanatical Muslim leader caused “deplorable injuries to the head.” Mamluk warriors are also believed to have used it as a target for shooting practice, meaning that it was shot up 500 years before Napoleon took the blame.

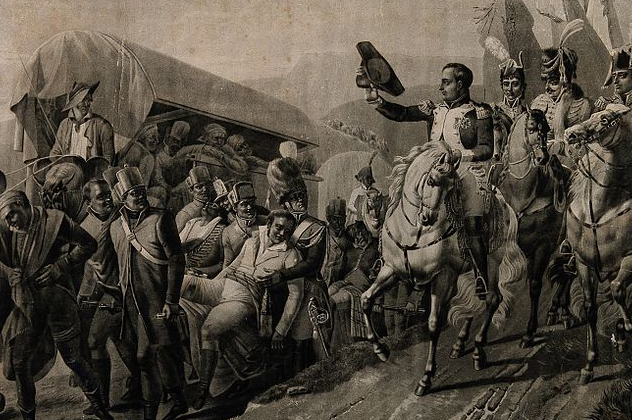

7Did Napoleon Poison His Wounded?

On May 27, 1799, Napoleon needed to retreat from the town of Jaffa in Egypt and had sent most of his wounded men ahead with necessary arrangements for their safety. But somewhere between 7 and 30 men were sick with the bubonic plague and could not be transported with the rest of the army for fear of spreading the infection. Napoleon realized that leaving these men behind would allow them to be captured by the Turks, who had a reputation for torturing prisoners to death. So Napoleon proposed to the doctor in charge, a man named Desgenettes, that it would be less cruel to end the lives of the sick men with a large dose of opium, a suggestion which the doctor refused to act on. In the end, Napoleon left a rear guard to protect the men, some of whom were found and rescued by the English after the retreat. This little episode exploded into a public relations fiasco for Napoleon. The story grew until it became a common belief that Napoleon had, in fact, performed the poisoning on several hundred men in Jaffa. French officers and soldiers believed it to be true and said as much when captured, and most of the English population believed the stories as well. The poisoning story followed Napoleon for the rest of his life. In 1804, Napoleon commissioned a painting (above) by Antoine-Jean Gros that displayed the soon-to-be emperor visiting the sick men at Jaffa in an attempt to quell the story of the poisoning which was still current in the British press. Gros’s work is now considered the first masterpiece of Napoleonic art and was influential in the establishment of the neoclassical school of art.

6Cleo Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

As the story goes, workmen at a Paris museum some time in the 1940s dumped the contents of a mummy case into the sewers while the museum was being cleaned. It was only later that it was realized that the case was being used to store the remains of Cleopatra, brought back from Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte. This particular myth was mentioned in 1996 in a book called Oops! A Stupefying Survey of Goofs, Blunders & Botches, Great & Small, by Paul Kirchner. The myth has only one major flaw: No one has yet found the burial place of Cleopatra, so no museum can claim to have lost her remains. The myth takes advantage of a general belief that Napoleon looted Egypt while he was there between 1798 and 1801. In fact, though Napoleon did attempt to take the country over by military force, he also brought 150 “savants”—scientists, engineers, and scholars—expressly so they could examine and record details of the monuments, artifacts, and history of Egypt while Napoleon was there. Though Napoleon’s political takeover of Egypt failed, the scholarly study he initiated resulted in a massive series of books about Egypt’s rich history, which sparked off a mania for everything Egyptian throughout Europe. So ironically, Napoleon’s scholarly interests may have resulted in Egypt being looted by every country other than France.

5Spooky Marengo

It has been reported that in June 1800, just before the Battle of Marengo, one of Napoleon’s generals urgently requested his attention. General Henri Christian Michel de Stengel entered the emperor’s tent looking somewhat forlorn, handed Napoleon an envelope, then informed him that it contained Stengel’s will and that he wished Napoleon to act as his executor. Stengel had awoken from a dream just a bit earlier in which he saw himself rush forward into the battle and be confronted by an enormous Croatian warrior in armor who then transformed into an image of death, and the general was thoroughly convinced that he would die in the upcoming conflict. Sure enough, Napoleon received a report on the following day that Stengel had died in battle with a very large Croatian warrior. The strange event haunted Napoleon the rest of his life, as reflected in his dying words at St. Helena years later: “Stengel, hurry, attack!” This particular myth has three strikes against it: First, Stengel died at the Battle of Mondovi, four years before Napoleon went to Marengo. Second, Napoleon’s last words are still a matter of debate, and no academic has ever asserted that “Stengel, hurry, attack” is a possibility. Three days prior to Napoleon’s death, while in a fever, he did call on Stengel as well as some of his other former generals to attack an imaginary enemy—but this is a far cry from what the myth asserts. Finally, the earliest mention of this incident is in 1890, around 100 years after it supposedly happened.

4He Fathered His Own Grandchild

When Napoleon married Josephine de Beauharnais, he also gained a step-daughter, Hortense, whom he loved and esteemed as his own child. When Hortense reached the right age, Josephine decided to try to marry her to Napoleon’s brother, Louis. This was partly because Josephine felt that Napoleon’s brothers were working to turn her husband against her, so having one of those brothers become her son-in-law would help quell this problem. Secondly, Josephine had been unable to give Napoleon an heir but was sure that if Hortense were to have a boy with Bonaparte blood in his veins, Napoleon would declare the child to be his heir to the throne. It took some creative argument, but, in 1802, Josephine finally got Napoleon to agree to the idea of marrying Hortense to Louis. And once Napoleon thought it was a good idea, anything Hortense or Louis felt about it ceased to matter. Surprisingly, a rumor started which stated that Napoleon was the actual father of Hortense’s upcoming child, and that this situation was arranged and encouraged by Josephine herself. More surprisingly, the rumor was started by Napoleon’s brothers, sisters, and in-laws who didn’t want Louis’s children to get special favor. The rumor was picked up by the British press with relish, who looked for every opportunity to mention the idea in print.

3Did He Send A Lookalike To Exile?

In 1815, Napoleon was exiled to live on the island of St. Helena, around 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) off the coast of Angola in southwestern Africa. According to history, this is where he remained for the rest of his life, dying there in 1821. But in 1911, a gentleman from France named M. Omersa claimed to have proof that Napoleon had never gone to St. Helena in the first place. Omersa asserted that a man named Francois Eugene Robeaut, who was known for his strong physical resemblance to Napoleon, was sent in the emperor’s place. Napoleon himself grew a long beard and went to Verona, Italy, where he had a small shop that sold spectacles to British travelers. The true Napoleon died in 1823 while trying to sneak into the Imperial Palace, where his son sat as king. Being unwilling to identify or explain himself to the sentry that caught him, he was shot on the spot. While intriguing, the story requires a conspiracy that involves the very warden of Napoleon himself, an unlikely prospect. It’s also unlikely that a soldier who just happened to look like Napoleon was able to convincingly—and willingly—play the part for the last six years of his life.

2The Supposed Chocolate Assassin

During Napoleon’s campaigns and reign, many stories were created by English propagandists to turn public opinion in England against him. And while most have long since been forgotten, a choice few live on. In 1905, a particularly creative example was published by Lewis Goldsmith. According to Goldsmith, Napoleon was staying at his uncle’s palace in Lyons prior to traveling to Italy. Napoleon was in the habit of having a cup of chocolate each morning, and one morning in particular he received an anonymous note warning him not to drink the cup delivered to him. When the chamberlain brought the drink, Napoleon demanded the person who prepared it be brought out, at which point the woman in question instead drank the remaining chocolate in the pot, then collapsed and started to have convulsions. Between convulsions, she revealed that she had been seduced by Napoleon when she was younger and had borne him a child, then been completely forgotten by him. Soon she expired, a victim of the poison she’d intended for Napoleon. The cook had seen the woman pour something from her pocket into the chocolate, and had therefore passed the warning to Napoleon. The cook was rewarded with a pension and induction into the Legion of Honour. Though certainly an untrue event, this story likely led to the current belief that Napoleon was very fond of chocolate, and the fictitious relationship is still quoted as a classic example of a spurned lover attempting to get revenge.

1A Timely Haircut

A surprising amount of Napoleon’s hair survived the emperor’s death. Historically speaking, it’s known that four locks of his hair were given to the Balcombe family, whom Napoleon had befriended during his exile on St. Helena. In addition, Napoleon bequeathed gold bracelets containing locks of his hair to a large number of his family and friends after his death. This fact has had some strange effects. One is that an authenticated lock of hair from the Balcombe family was used to test the theory that Napoleon had been victim to arsenic poisoning. Another effect is that false locks of Napoleon’s hair have been produced by a variety of con men for nearly 200 years, and still go for thousands of dollars if suspected of being real. But undoubtedly the most unexpected—and possibly most appropriate—effect is that a Swiss watch manufacturer, who bought locks of Napoleon’s hair at auction, announced in November 2014 that they were now making watches that cost $10,000 each, and that each would contain a single hair from Napoleon Bonaparte himself. So, 200 years after Napoleon requested his hair be made into bracelets for family and friends, his hair will once again be made into “bracelets” for a new generation of adoring—and rich—fans.

+How Did General Stengel Die?

A funny thing about history is that it occasionally changes for no good reason. Case in point: the actual death of General Henri Christian Michel de Stengel. According to a letter written by Napoleon himself dated April 27, 1796, Stengel was killed on the field during the battle at Mondovi. Napoleon’s word on the matter was good enough for historians until 1896, when a new story started to be told—some books began to claim that Stengel died a week after the battle at Mondovi due to complications from an operation to amputate his left arm. The new day of death became April 28, 1796, one day after Napoleon wrote the letter which stated that Stengel had died in battle. A review of books on Napoleon’s campaigns over the past century shows two things—first, Stengel’s death is just not often mentioned. Second, when his death is mentioned, about half of the books and articles state that Stengel died in battle while the other half state that he died from the amputation. As a result, the amputation story—with no known supporting documents and in direct defiance of Napoleon’s own statements on the matter—has become just as commonly told as the alleged truth. There appears to be no historian who has ever acknowledged the existence of the two stories and studied them; this is perhaps because General Stengel, when you get right down to it, is a relatively minor historical figure. Tough luck, Stengel! Garth Haslam has a degree in anthropology and specializes in folklore and religious studies; he’s been digging into strange topics for over 30 years, and posts his research on varying anomalies, curiosities, mysteries, and legends at his website Anomalies—The Strange & Unexplained. Check it out at http://www.anomalyinfo.com.