10 Bobo Gets A Beating

In 1961, Albert Bandura’s landmark experiment showed that children could learn aggressive or violent behaviors simply by being exposed to them. This contradicted the prevailing view that learning required rewards or punishment. Bandura worked with three groups of nursery school children. The first group watched an adult showing aggressive behavior toward an inflatable clown called Bobo, kicking and hitting it. The second group observed a nonaggressive adult, who did not engage with the clown. The third group wasn’t exposed to either behavior. Later, the children were left alone in a room with the inflatable doll and several other toys. The children who had watched an adult being aggressive and violent toward Bobo were much more likely to kick, hit, and attack the clown doll. Exposure to these behaviors made children more likely to adopt them—even if the adult didn’t instruct or reward the child.

9 Who’s That Baby In The Mirror?

In her 1972 study, Beulah Amsterdam of the University of North Carolina kicked off a series of mirror experiments to test children’s self-awareness. Researchers put a spot of rouge on the noses of children aged six months to two years, put them in front of the mirror, and had the child’s mother ask, “Who’s that?” At 6–12 months old, the children thought they were seeing another baby and approached it. But by 20–24 months, most of the children understood they were seeing themselves and pointed to the rouge on their nose. In the middle group (about 12–20 months old), many of the children were unsure and even avoided the image. They no longer assumed the baby in the mirror was a new friend, but they didn’t seem to quite understand that it was their own reflection.

8 The Science Behind Tickling

In 1933, psychologist Clarence Leuba wanted to determine if laughter was an inborn reaction to being tickled or if children learned from social cues that laughing was the appropriate reaction. To find out, he decided that his newborn son would only be tickled during specified experimental periods. To prevent Leuba’s own facial expressions from influencing the child, he wore an expressionless mask during all experimental tickling. Even so, Leuba’s son did reliably laugh when tickled. The experiment seemed to be a (slightly creepy) success. One day, Leuba’s wife supposedly “ruined” the experiment with some unsanctioned tickling of their son after a bath. To collect more data, the psychologist repeated the tickling experiment on his second child, a daughter. This at least ensured that the siblings could save money in the future by splitting the cost of a therapist.

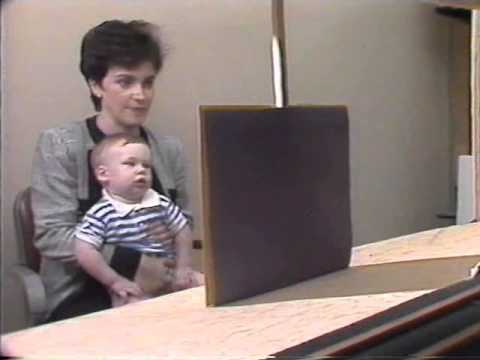

7 Making Babies See The Impossible

In 1985, Professor Renee Baillargeon of the University of Illinois devised an experiment to find out if infants understood the concept of object permanence, which means that an object continues to exist even if you don’t see it. For example, we know that the Eiffel Tower continues standing in Paris even if we aren’t currently looking at it. Baillargeon showed infants aged 6–8 months a toy car rolling down a ramp with a portion of the car’s path hidden by a screen. Then a solid block was laid next to the track and covered by the screen. Finally, a solid block was laid across the track (blocking the car’s path) and then was obscured by the screen. Each time, experimenters released the car onto the ramp again. However, they manipulated the final condition so that the car reappeared (even though it should have been stuck behind the hidden block lying on the track). Baillargeon found that infants consistently looked longer when shown an “impossible” event, which means that they realized something was wrong.

6 The Marshmallow Test For Success

One of the most famous child psychology experiments is the Marshmallow Test, led by Walter Mischel in the 1960s. In the experiment, an adult presented each child (ages three to five) with a reward, such as a marshmallow, but then offered the kid a deal. The adult explained that if the child did not eat the marshmallow while left alone in the room, he could have two marshmallows when the researcher returned. If the child couldn’t wait, he could ring a bell. Then the adult would return, and the child could eat the single treat. About 30 percent of the kids were able to wait for the adult (about 15 minutes) and earn the additional treat. Years later, Mischel collected data on the participants and found that those who ate their treat quickly tended to have lower SAT scores and higher body mass index levels.

5 The Broken Toy Experiment

What makes a person understand and care that their actions affect others? Grazyna Kochanska and her colleagues at the University of Iowa believe that a child’s ability to feel guilt is an important factor. To test this hypothesis, an adult researcher showed a toy to a child and explained that it was very important to the adult. Then the child was left alone with the beloved toy, which was designed to fall apart as soon as the child engaged with it. When the adult returned and found the broken toy, researchers recorded the children’s reactions—from avoiding the adult’s eyes to covering their faces with their hands. In the end, the researchers did let the kids off the hook. The adult returned with an intact copy, saying the toy was fixed. The most guilt-prone kids may have suffered more initially, but Kochanska observed that they had fewer behavioral problems during the following five years.

4 Little Albert’s Fear Of Fluffy Things

In 1920, John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner taught a nine-month-old boy known as “Little Albert” to be terrified of fuzzy animals. When they first presented Albert with a white rat, he was unafraid. But when the researchers brought the animal to Albert again, they paired it with a loud, jarring sound by hitting a steel bar with a hammer. The sound startled and scared the baby, launching him into an emotional fit. After a few repetitions, the sight of the white rat alone caused Albert to cry and withdraw from the animal. By associating the harmless rat with an unpleasant, scary stimulus, Watson and Rayner created a fear that Albert then generalized to rabbits and other fuzzy animals.

3 Training Children To Stutter

In 1938, University of Iowa Professor Wendell Johnson, a psychologist who had stuttered from childhood, and graduate student Mary Tudor created an experiment to prove his theory that stuttering was a learned behavior, not a genetic condition. Taking advantage of the university’s relationship with a nearby orphanage, they selected 22 children (ages 5 to 15) for their experiment. Ten children already stuttered, and 12 didn’t. The non-stutterers were split into two groups, one of which was told that their speech was fine. The other group was told by researchers that their speech was abnormal and they must fix it. Furthermore, researchers criticized this second group of children when they misspoke. The experiment failed utterly. Of the six children in this subgroup, only two became less fluent speakers. Sadly, even though these children did not become stutterers, they did become less talkative and more self-conscious.

2 Will Your Baby Crawl Off A Cliff?

Fortunately, crawling off a cliff isn’t a common risk for a baby. But Cornell University researchers Eleanor J. Gibson and Richard D. Walk put together an experiment in 1959, just in case the situation ever came up. The scientists wanted to find out if babies could visually perceive a drop like a cliff and if they would refuse to cross it. To safely test the infants, Gibson and Walk built what they called a “visual cliff.” They placed a thick piece of glass over a multileveled patterned base. This gave the illusion that if the infant crawled past a certain point, they would fall. On the side of the structure that appeared to be empty space, the child’s mother called for the baby to join her. But infants as young as six months both perceived and avoided the visual cliff. It is unknown whether the mothers beckoning their children to crawl off a cliff led to trust issues among the subjects.

1 Growing Up Chimp

In 1931, Winthrop Niles Kellogg wanted to take an animal out of the wild and raise it as a human. This is how his infant son, Donald, ended up with a chimpanzee for a sister, if only for nine months. The experimenter brought home a seven-month-old chimp named Gua when Donald was 10 months old. Both Kellogg and his wife treated Gua just like their human child and measured both of them in a wide variety of aptitudes, including attention span, problem solving, and memory. In the beginning, Gua kept up with and sometimes even outperformed Donald. But eventually, her natural limitations prevented her from learning language and other skills. While the exact reason the experiment was ended is up to speculation, its detrimental effects on Donald were probably a factor. The child was slow to pick up new words and even imitated the barking sounds Gua made to request food.