In fact, they are changing the way pterosaurs looked, existed, and ultimately died out. Even so, their complete story remains mysterious and contentious. More than any other creature, pterodactyls can make researchers go a little crazy.

10 Flightless Young

Scientists debate whether pterodactyls could fly directly after hatching. In 2017, a cache of eggs proved that there was no such independence. Around 16 eggs were perfectly preserved, allowing scans to reveal complete skeletons in 3-D. The thighbones were strong, but those supporting the pectoral flight muscles were underdeveloped. This meant that hatchlings could probably walk but not soar into the sky. None of the youngsters had teeth, either. Both the flightless vulnerability and the lack of teeth would have made life dangerous for baby pterodactyls. Another find suggested parental protection. Close to where the 120-million-year-old clutch was found in China, adults of the same species turned up. They were male and female H. tianshanensis.[1] The number of eggs in the area, over 200, pointed at colony breeding behavior. The soft shells of the eggs also indicated that, much like modern reptiles, pterodactyls buried their eggs to prevent the embryos from drying out.

9 Mysterious Plane-Sized Species

In 2017, paleontologists stuck their spades into the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. They focused on a rich fossil mine. Since the bone patch never produced a pterosaur, it came as a surprise when huge neck bones turned up. They were cervical vertebrae of such immense size that the creature was estimated to match a small plane. The species has not been identified. But it lived around 70 million years ago and was probably one of the biggest pterodactyl species ever to exist. Calculations suggested that the animal terrorized the sky with an 11-meter (36 ft) wingspan. Confirmation will have to wait, however, as the rest of the body remains missing. It is also possible that the species was average or small but developed jumbo necks for some reason. At least, the discovery proved that the flying predators were more widely distributed that previously thought—it was the first of its kind to be discovered in Asia.[2]

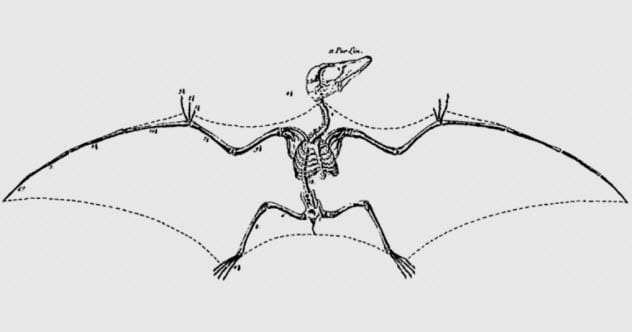

8 The Quail Study

In 2018, researchers claimed that paleontologists were wrong about pterodactyls—specifically, about how the animals’ hip joints were portrayed in flight. They drew on a 19th-century depiction of a pterosaur posing like a bat. Claiming this was impossible, they went on to say that close to 95 percent of pterosaur and dinosaur reconstructions were wrong. This conclusion came after the common quail showed similar thighbones to those of pterosaurs. A dead quail’s skeleton splays like a bat’s, but living muscles and ligaments prevented the pose. The study was not welcomed. Birds descend from a certain dinosaur lineage, but pterosaurs were not dinosaurs. According to the strange study, pterodactyls had similar femurs to quails. But other scientists pointed out that the bone structure surrounding the hip joint had nothing in common with birds. Several facts were also ignored, including new research on the reptiles’ pelvic muscles and tracks showing how they walked. Additionally, scholars had dismissed the 19th-century sketch as incorrect years ago. A lot about pterodactyls remains unknown, but this baffling attempt with quails and long-acknowledged mistakes certainly does not help.[3]

7 They Breathed Strangely

Pterodactyls did not breathe like people. They possessed an unusually rigid chest, which could not expand to inhale or squeeze out old air. Extra air sacs existed in their bones, just like birds, but the two could not have breathed the same way. Birds rely on the up-and-down movement of their sterna to regulate breathing. Once again, pterodactyls were just too stiff. In recent years, living reptiles—crocodiles and alligators—gave the best answer. They breathe via something named the hepatic piston. This odd technique involves the liver, which separates their guts and lungs. The liver contracts and shoves the guts down, making space for the lungs to inhale. Belly ribs return the liver to its original position, and the croc exhales.[4] Pterodactyls could have used a similar method. Sure, their chests were ridiculously tight. Some species had fused vertebrae and ribs, along with dense networks of mineralized tendons. However, there was a method to this madness. It strengthened their skeletons and lowered muscle mass. This allowed pterosaurs to become the largest animals that ever flew.

6 When Pterosaurs Are Turtles

In 2014, paleontologists Gerald Grellet-Tinner and Vlad Codrea identified a 70-million-year-old new species called Thalassodromeus sebesensis. Oddly, this genus already existed—pterosaurs that soared above Cretaceous Brazil around 42 million years earlier. If this was the same animal, then a massive chunk of its history was missing from the fossil record. Grellet-Tinner and Codrea attempted to patch the hole with migration, evolving alongside flowering plants and how islands could have altered the species. Despite this elaborate backstory, the Romanian fossil stayed out of place. During publication, the single piece was called a “snout.” When other paleontologists reviewed the study, they knew why the new species could not fit. It was a turtle. The plate matched the belly shell from a Kallokibotion—a turtle from the Cretaceous.[5] Despite Kallokibotion‘s presence in Romania being known for almost a century and the fact that nobody agreed with them, the authors persisted with the conviction of a pterodactyl. Worse, this misidentification could muddy research with a creature that never existed.

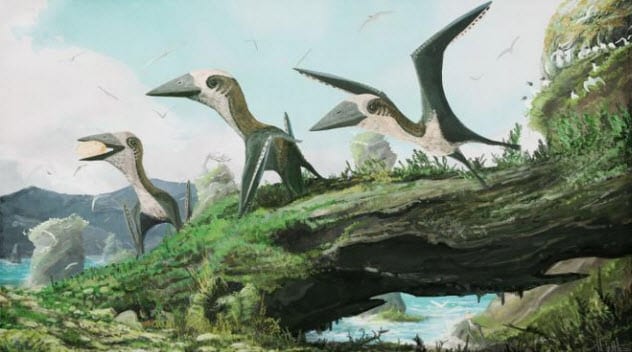

5 Pterodactyls From Hateg Basin

Hateg Basin was an island where animals existed in dwarf form. During the dinosaur era, several species roamed Hateg as diminutive versions of their larger counterparts on the mainland. Oddly, the island produced giant pterodactyls. It would appear that a lack of big predators, like tyrannosaurs, gave the flying reptiles the chance to become the fright factor on the island. The tallest was Hatzegopteryx, which could have looked a giraffe in the eye. Its wingspan measured 11 meters (36 ft), but the lengthiest wings on the island went to another pterodactyl, cutely nicknamed “Dracula,” with a span of 12 meters (39 ft). In 2018, researchers identified the biggest pterosaur jawbone in history and it came from Hateg. The 66-million-year-old fossil was found decades ago but was only recently recognized for what it was. In life, the unnamed species sported a jaw that was 94–110 centimeters (37–43 in) long. However, this does not mean that it was the largest pterosaur. Researchers believe that it had a smaller wingspan—around 8 meters (26 ft)—than the giraffe guy and Dracula.

4 The Most Complete Skeleton

Pterodactyl fossils are exceptionally scarce. From the Triassic Period (220 million years ago), only 30 individuals have been found, often in the form of single fragments. Recently, researchers removed a living-room-sized block from a quarry in Utah that is known for tightly packed Triassic fossils. Back at the laboratory, the team chiseled out a few ancient crocodiles and then made a smashing find. Among the block’s 18,000 bones sat a pterosaur. At least, it was the most complete one ever found with a partial face, intact skull roof and lower jaw, and a portion of a wing. Scans soon identified a new species, Caelestiventus hanseni. This juvenile grinned with 112 teeth and had a bony jaw appendage, probably to support a pelican-like throat pouch. The brain suggested sharp sight but a poor sense of smell.[7] The best information concerned the Triassic-Jurassic extinction. The rare fossil appeared to be related to another species from the later Jurassic, which means that C. hanseni‘s lineage conquered a terrible event that wiped out innumerable species.

3 Cretaceous Surprise

By the end of the Cretaceous, their last era, all pterodactyls were supersized. Scholars felt the competition was so stiff that the flying reptiles had to be huge to survive. The ecological niche that once supported small pterosaurs was taken over by birds. In 2008, a fossil hunter found a rock on Canada’s Hornby Island. About as big as a softball, the chunk contained visible vertebrae. After initially examining the rock, the fossil hunter concluded that it was a “flying something.” When researchers got their hands on the specimen, it challenged the Cretaceous pterosaur story. The vertebrae, aged 70–85 million years, had a special design linked to flight, something not present in Cretaceous birds.[8] The remains suggested an adult pterodactyl no bigger than a cat. Since the bones were few, researchers hesitated to name a new species or mash its existence into the evolution story of pterosaurs. However, this is a fantastic find. This pint-sized predator, which could still turn out to be a known species, existed when everyone said they should not.

2 They Were Fluffy

We can now burn the books depicting pterosaurs as leather-naked creatures. It is official—they were covered in feathers. Not just a tuft here and there, either. When scientists examined two pristine fossils in 2015, they identified four types of feathers. Found in China, the reptiles sported down, single filaments that resembled hair, filament clumps, and filaments with fluff in the middle. Although it remains unclear if the pair belonged to the same species, both dated to approximately 165–160 million old and came from the same fossil bed. Additionally, the creatures had preserved soft tissues. Surviving pigment suggested that the feathers were rust-colored, which could have been significant in camouflage or communication. Like modern birds, pterodactyl feathers could also have insulated the body or been used for streamlining flight or tactile sensing. They may share the four types with certain dinosaurs, but the pterodactyls boasted special honors. The discovery of the fluffy pair pushed the origins of feathers back 70 million years.[9]

1 Killed In Their Prime

A long-standing belief claimed that pterodactyls slowly became extinct by themselves. Supposedly, by the time the dinosaurs became extinct 66 million years ago, pterodactyls were few. However, a 2018 study crushed this theory. The story begins with pterodactyl-obsessed student Nick Longrich, who later went on to professionally study fossils. While excavating in Morocco, he found a tiny bone. Having studied the book on pterosaurs to the point of religion, Longrich recognized that the bone belonged to the nyctosaurs, a group of smaller pterodactyl species. This initiated a slew of discoveries, including seven species from three different families. The best were pteranodontid bones, a group thought to have gone extinct 15 million years before. The fossils belonged to the late Cretaceous when an asteroid is believed to have killed the dinosaurs. Their diversity showed that the studies were wrong. They did not fade away on their own. When the asteroid arrived, pterosaurs were varied and going strong. After soaring through the skies for 150 million years, it was the space rock they could not beat.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages