10His Grim Childhood

Roald Dahl’s childhood began much like one of his novels. His father and sister died weeks apart, leaving Dahl’s mother to raise him alone with five other children. Later, he was in a car crash where he was thrown through the windshield, severing his nose from his face and forcing reconstructive surgery. Dahl recounts several incidents from this period—recorded in his autobiography Boy—that wouldn’t seem out of place in his fiction. For example, one story in Boy relates to an accident that Dahl’s father suffered as a teenager. He fell from a roof and broke his arm. The doctor was dead drunk and misdiagnosed the injury as a dislocated shoulder. The doctor then ordered two stout men to hold on to the boy’s waist while he pulled from the wrist. The damage was so severe that Dahl’s father ended up losing the arm. In another incident, Dahl recounts how he and his friends clashed with the witch-like proprietor of a candy shop—they tried to even the score by placing a dead mouse in her gobstopper jar, as acted out in the above video. She found out and made sure that Dahl and his friends were caned, all the while watching, cackling, and encouraging the headmaster to hit them harder. Later, he attended a boarding school where he witnessed severe cruelty. It’s believed that this period in his life influenced many of his later children’s stories that dealt with the recurring motif of child abuse.

9His Plane Crashed And Made Him A Writer

Roald Dahl was working for the Shell oil company in Africa when World War II was declared. Like many others, he handed in his resignation and signed up as a fighter pilot. After flight training, he undertook his first solo flight in 1940. He received incorrect coordinates—he was supposed to rendezvous with the rest of his squadron but was instead directed to an empty patch of desert, which he circled until he ran out of gas and was forced to crash-land. He was taking the plane in for landing when its back end hit a boulder. Dahl’s face smashed into the reflector-sight with such force that it fractured his skull and flattened his nose, driving it back into his head. Through some miracle, he managed to get out of the burning plane just as the fire caused the plane’s barrels to discharge all its machine-gun ammo—which, luckily, never hit him. He did all this while blind and on fire. Dahl’s injuries were severe. He spent months convalescing in an Egyptian hospital (most of that time completely blind) and suffering terrible headaches. He was adamant that the head injury had somehow changed his personality, rewiring his brain and turning him from a corporate man into an artist. Maybe it did. He spent his recuperative time writing, and one of his first published stories began as a totally factual account of the crash.

8He Then Fought In The Battle Of Athens

After recovering from his injuries, Dahl was reassigned back to his squadron, now based in Greece. German forces had joined with the Italians, so the situation looked quite hopeless for Dahl’s squadron. Nevertheless, on April 20, 1941, Dahl and the other pilots flew in formation over Athens to boost morale by showing the people of Athens that the British were still there. This turned out to be shortsighted. While Dahl’s squadron flew over Athens, up to 200 German planes came out of nowhere, outnumbering Dahl’s squadron almost 10 to 1. According to Dahl, there were so many German planes that they started accidentally taking one another out by crashing into each other. Dahl describes it thusly: “I can remember seeing our tight little formation all peeling away and disappearing among the swarms of enemy aircraft, and from then on, wherever I looked, I saw an endless blur of enemy fighters whizzing toward me from every side. They came from above, and they came from behind, and they made frontal attacks from dead ahead, and I threw my Hurricane around as best I could, and whenever a Hun came into my sights, I pressed the button. It was truly the most breathless and in a way the most exhilarating time I have ever had in my life.” At least four from the tiny squadron died in the battle.

7He Was A Seductive Spy

In the early days of World War II, Britain was desperate to bring the United States into the war. But this wouldn’t be easy, as polls stated that 80 percent of Americans opposed combat. To turn things around, Churchill set up an organization called the British Security Coordination (BSC) to change American public opinion. The BSC was run from the 35th floor of Rockefeller Center by a spymaster called William Stephenson (code name: Intrepid). It aimed to influence Americans through propaganda by circulating fake, anti-German news stories to radio stations and newspapers nationwide. A group of high-profile figures were recruited to gain American support, smear Americans who opposed the war, and unmask Nazi sympathizers. Churchill called this group “The Irregulars” after Sherlock Holmes’s network of Baker Street Irregulars. Some of the Irregulars’ more well-known members included Ian Fleming, Noel Coward, and Roald Dahl. During this time, Roald Dahl was effectively James Bond, especially when it came to sleeping with women to complete his mission. After sleeping with an older female politician to change her stance on Britain and the war, he once wrote that he was “all f—ked out,” as the congresswoman “had screwed [him] from one end of the room to the other for three goddam nights.”

6He Hung Out With Ernest Hemingway

We’ve previously mentioned Hemingway’s time as a war correspondent. Hemingway was only supposed to write about the war, but he ended up creating a ragtag group of soldiers to carry out guerrilla attacks, instead. However, Hemmingway originally shipped off to Normandy because of two different people—his wife and Roald Dahl. His wife, Martha Gellhorn, concerned about Hemingway’s excessive drinking, asked Dahl if he could pull some strings to get Hemingway over to England. She hoped this would have a sobering effect on him. Dahl had met Hemingway and Gellhorn a fortnight earlier in New York where they’d boxed, drunk champagne, and eaten caviar. After Gellhorn’s request, Dahl used his BSC contacts to get Hemingway a flight to London, where he was then hired by the RAF to write about the war. We’ll probably never know how well the two got along, as Dahl mentioned little about his experience with Hemingway. Perhaps his previous respect for the man somewhat lessened upon discovering Hemingway’s notorious vanity. In one incident, Dahl caught Hemingway staring in a mirror and fastidiously applying hair growth formula to a bald spot on the back of his head. Hemingway made Dahl wait while he methodically rubbed the liquid into his scalp.

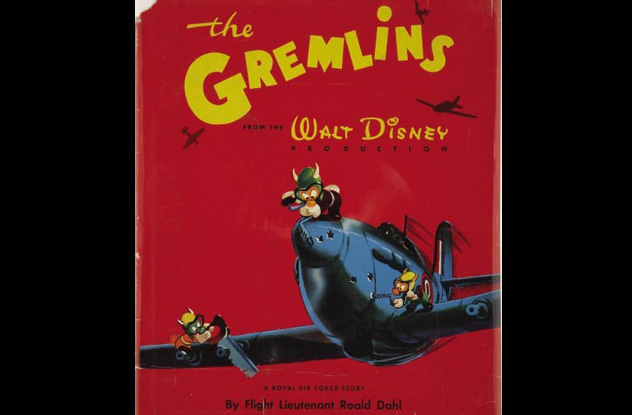

5He Popularized ‘Gremlins’

The term “gremlins” began as a piece of Royal Air Force slang to describe the cause of random mechanical failures. If a plane fell out of the sky and nobody could figure out why, it was blamed on “gremlins.” Roald Dahl was the first writer to really popularize the term in his first children’s book The Gremlins, written while convalescing from his plane crash. In Dahl’s story, the Gremlins originally live in the forest until the Royal Air Force flatten their homes to make space for military installations. The Gremlins then take revenge by hiding on planes and sabotaging them in midair, until the novel’s protagonist convinces them to join forces with the RAF to fight Hitler. Dahl sent the manuscript to the RAF for approval. They forwarded it on to Walt Disney, who decided it would make a good movie. But the movie never materialized, due to several reasons. Dahl was difficult, insisting on full creative control, and the RAF interfered as well. The term “gremlins,” not invented by Dahl, was in such common use that Disney couldn’t copyright it. Plus, there was a war going on. Gremlins would later reappear in the Twilight Zone episode “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” several Merrie Melodies cartoons, and the 1983 movie of the same name. How much these were inspired by Dahl is anybody’s guess.

4Robert Rodriguez And Quentin Tarantino Have Adapted Dahl Stories

Roald Dahl is clearly most well known for his children’s stories, like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, The BFG, and many more. However, Dahl also had a parallel career as a writer of dark, adult short stories. To give you an idea of just how different these tales were from his children’s stuff, one recurring character (Uncle Oswald) was an erotic adventurer described as “the greatest bounder, bon vivant, and fornicator of all time.” Watch this video on YouTube Many of these darker stories were later adapted into a Twilight Zone–style TV show called Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected. Then in the ’90s, some of them were adapted into four segments in the 1995 anthology movie Four Rooms. The film comprised four stories, focusing on customers a bellhop (Tim Roth) is forced to deal with on one busy New Year’s Eve. Each of these segments is directed by a separate director. For example “The Man From Hollywood” (viewable above) is an adaptation of Dahl’s tale “The Man From The South” and is directed by Quentin Tarantino (who stars in it alongside an uncredited Bruce Willis). “Room 309,” starring Antonio Banderas, is directed by Robert Rodriguez and is an adaptation of “The “Misbehavers.” There are also two other segments directed by Allison Anders and Alexandre Rockwell. We won’t spoil the plots for you, but if you’re a fan of anthology films and Roald Dahl, this one’s definitely worth watching.

3His Son’s Accident

In 1960, Roald Dahl and his family were rocked by a terrible incident that occurred in New York. Dahl’s nanny, Susan Denson, was bringing Theo, Dahl’s four-month-old son, home from nursery school. She was struggling with the baby and the family dog, and a taxicab ran a red light and hit the buggy. Realizing what he’d done, the taxi driver panicked and tried to hit the brakes but instead accidentally accelerated and catapulted Theo’s buggy 10 meters (40 ft) through the air. Theo was thrown against the side of a bus, shattering his skull. Somehow, Theo survived the incident, but he was badly injured and later diagnosed with a neurological deficit. He suffered through several operations and was eventually fitted with a tube to drain excess cranial fluid. This didn’t work well, and Theo was shuffled back and forth to the hospital whenever the tube became blocked. Dahl decided to fix the problem himself. He contacted Stanley Wade—a friend of his who built model aircraft engines—and a doctor named Till. The three of them worked together for a month to create the Wade-Dahl-Till cerebral shunt, a small cylinder with two shutters designed to allow fluid to flow both ways. By the time the device was tested and ready, Theo had gotten better on his own. However, the Wade-Dahl-Till shunt went on to replace the existing shunt and save the lives of thousands of children all over the world.

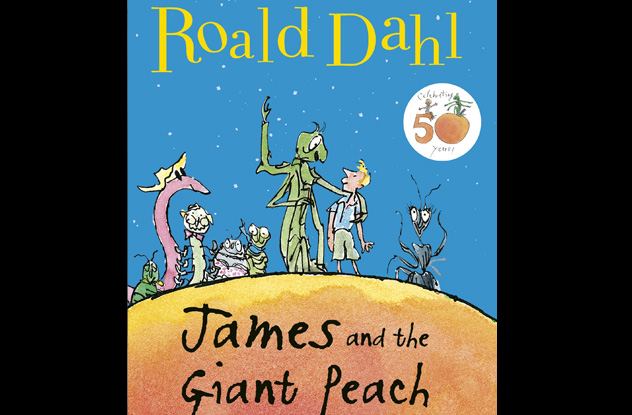

2Return To Children’s Fiction

As stated earlier, Dahl was mostly a writer of adult fiction in his earlier career; after Gremlins came a 20-year gap before he wrote another children’s story. One of the reasons he went back to children’s fiction, according to Dahl himself, was that he started making up bedtime stories for his own children. These would eventually evolve into James and the Giant Peach. Dahl said, “[I]t’s very hard to come upon a genuine short-story plot. Anyway, I had children and couldn’t think of any more short stories. So I thought, why don’t I write a children’s book?” Around this time, his own career was stagnating. He wrote a lot, but he mostly ended up adapting novels into screenplays. For example, he wrote the screenplay for The Night Digger, a 1971 slasher film about a sexually inadequate serial killer. He wondered if he’d have more success crafting his tales for a younger audience and wrote James and the Giant Peach in the space of six months. Although Dahl had little trouble getting the book published in America, British publicists found the book a little too dark and grotesque for British children. He spent some seven years shopping the book around to at least 11 different British publishers, who all rejected him. He finally took matters into his own hands and paid half the publishing fees for the books to be printed in the Czech Republic and sold at a discounted rate in the UK. It was a bold risk that could have ruined him, but it paid off.

1His Remaining Papers

Most of Dahl’s children’s literature was written in a small gypsy caravan at the bottom of his garden. Since his death in 1990, his papers have been pored over, and a few weird details have emerged. It’s clear that Dahl was a very meticulous writer who reworked his ideas time and time again. For example, in an early draft of James and the Giant Peach, James rides away on a giant cherry. Matilda is also notably darker in its first draft, with Matilda dying at the end. In an early version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the title is Charlie’s Chocolate Boy (a reference to Charlie being black in this version). Here, Charlie is a boy who falls into a chocolate machine and ends up as an ornament on Willy Wonka’s mantle. As far as we know, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is Dahl’s most reworked piece. Originally, Dahl wanted around 15 children to enter the chocolate factory. He pared this down to six, one more than in the version we all read. The sixth child was Miranda Mary Piker. Although all the children survive in the final draft (albeit flattened, stretched, blown up, and/or purple), Miranda Mary Piker dies after falling into the Crunch Munchy Peanut Brittle Bar machine. Perhaps, that’s why she was cut. Aaron Short is a freelance writer and film student. You can contact him on Twitter if you’d like to chat about anything.