10 Zenigata Heiji

Invented by the Japanese author and music critic Nomura Kodo (1882–1963), Zenigata Heiji was a feudal policeman of the Edo period. Living in a spartan tenement, he was a goyokiki, a poor assistant of low status, for a higher-ranking doshin (“police official”) named Sasano. As Zenigata Heiji was not a samurai, he was forbidden to carry a sword or bladed weapon. Instead, he would throw heavy coins at bullet-like speeds to stun his opponents or use a jutte (heavy truncheon) to disarm criminals without spilling blood. Needless to say, while the latter was based on historical fact, the former was a flamboyant literary invention that helped to define the character. Zenigata Heiji was notable for both his deductive prowess and his humanistic qualities, being more likely to view criminals with sympathy while abhorring their crimes. His loyalty was to the common man rather than the high-ranking samurai, whom he often resented and who often thought of him as a failure despite his successes. He wasn’t a perfect figure, however, with his habits of heavy drinking and smoking. He learned of crimes from a compatriot named Hachigoro, who played the Watson to his Holmes and kept him well supplied with gossip and rumors from the common people. Zenigata Heiji would later become a popular figure in the historical television dramas known as jidai-geki, where the feudal police and their investigations were as much a mainstay of the genre as the sheriff in American westerns.

9 Papa LaBas

Created by African-American writer Ishmael Reed in the novels Mumbo Jumbo (1972) and The Last Days of Louisiana Red (1974), Papa LaBas is a private eye who describes himself as a “jacklegged detective of the metaphysical.” He works in New Orleans and uses hoodoo to solve crimes. His place of work is called the Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral, “a factory which deals in jewelry, black astrology charts, herbs, potions, candles, talismans. People trust his powers. They have seen him knock a glass from a table by staring in its direction and fill a room with the sound of forest animals.” He cuts a striking figure, described as wearing “his frock coat, opera hat, smoked glasses and carrying a cane.” The character is a reference to and stand-in for the Haitian loa Papa Legba, who was descended from the West African deity Eshu/Elegbara (the lord of transitions) who acts as both a trickster deity and a facilitator of communication. Some critics consider the characterization of Papa LaBas as representing Reed’s criticism of Western rationalism as the only source of truth. They refer to the first novel as an “anti-detective” story that prefers to celebrate a mystery rather than solve it. The novels were derived from Reed’s philosophy of neo-hoodoo, a jazzlike prose aesthetic featuring multiple stories and styles and a rebellious attitude toward tradition.

8 Inspector O

James Church is the pseudonym of a CIA intelligence officer who spent 30 years working in East Asia. He used this experience to create Inspector O, first introduced in the 2006 novel A Corpse in the Koryo. O is a brilliant North Korean police inspector who must try to solve crimes in the corrupt, paranoid, and Kafkaesque society in which he lives. Church has described the novels as an attempt to show how an intelligent, rational human being is forced to behave and operate in a country like North Korea—even if O is skeptical about the government, is constantly stymied in his investigations by totalitarian bureaucracy and the lack of resources, and spends most of the first novel just trying to get a nice cup of tea. “The character had to fit into the real North Korea,” Church explained to The Independent in an interview. “It is very important to humanize the situation and crystallize my experience of real people dealing with real problems in North Korea, with the additional problem of living under a social system that puts them under incredible pressure.” Many of the crimes O tackles often lead to convoluted plots, intrigue, and intimate ties with North Korean politics and history, such as a bank robbery tied to a possible coup attempt and the murder of a diplomat’s wife in Pakistan ultimately linked to the North Korean famine of the 1990s. While the Kim family is never mentioned by name, they are a constant, looming presence referred to as “the center.” Church maintains his pseudonym so that he can continue to travel to North Korea undetected and observe everyday life for use in his fiction. As he told The Independent: There were people who said to me, if you get arrested they will take you into an interrogation room and you’ll learn a lot about interrogation techniques. I said I don’t want to do that. Half is imagination, and half is putting together what I know about how North Korean [authorities] operate, how creepy it is in some cases, how it works against itself. I worked in a bureaucracy for a long time, so it’s not just Korea.

7 Lord Darcy

Although science fiction author Randall Garrett is little known today, he was hailed as one of the premier creators of his generation in the mid-20th century. His most enduring creation was the character of Lord Darcy, an occult detective from a parallel reality where Richard the Lionhearted did not die in 1199. Instead, he survived to build a lasting Anglo-French empire under the Plantagenet dynasty that endured into the 20th century. Working under the auspices of the Duke of Normandy, Lord Darcy worked in a universe where the laws of magic applied, which he used to solve crimes like Sherlock Holmes used scientific deduction. Legend has it that the character was created as the result of a bet between Isaac Asimov and Garrett. Asimov believed it would be impossible to plausibly set a “fair-play” detective story in a science fiction or fantasy world because the protagonist would inevitably whip out some piece of advanced technology or magical artifact to solve the mystery. Garrett disagreed and created a fantasy world where the laws of magic are rigid and clearly defined, a projection of psychic power with severe limitations. Chief Forensic Sorcerer Master Sean O’Lochlainn, Lord Darcy’s assistant, is able to ascertain when a crime has been committed by mundane rather than magical means. Therefore, while Lord Darcy uses alchemy and sorcery in his investigations, he must also rely on deduction and analysis to uncover the truth. This may be why the stories were covered in the science fiction magazine Analog, which did not otherwise publish works of pure fantasy.

6 Omar Yussef Sirhan

Welsh-born journalist Matt Rees, the former Jerusalem chief for Time magazine, spent nearly a decade studying the Israel-Palestine conflict, authoring a book on the subject entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East. He later used his extensive experience to create the character of Palestinian detective Omar Yussef Sirhan, first introduced in his 2006 novel, The Bethlehem Murders, which was followed by three other adventures. As an Arab nationalist and history teacher, Sirhan is an unlikely figure to be thrust into crime investigation. He relies on intelligence, moral arguments, and the threat of reprisal from his clan to hold his own against more violent adversaries in his investigations. He cuts an unusual figure, making his way through refugee camps carrying a purple briefcase and wearing excessively well-tailored clothing, a comb-over, and mauve shoes. He is protected by his membership in the Sirhan clan, which includes members of Hamas, Fatah, and other Palestinian political organizations. Rees has been praised for telling uniquely Palestinian stories. The Israelis form an inevitable part of the backdrop, but they are not the focus of the investigations. While Rees used his intimate knowledge of Palestine to flesh out the character of Sirhan, the novels themselves are steeped in Palestinian cultural influences—from the direct translation of cultural expressions to generous descriptions of local cuisine. Rees has been praised for exploring knotty political and historical issues through the medium of a dogged and analytical detective hero.

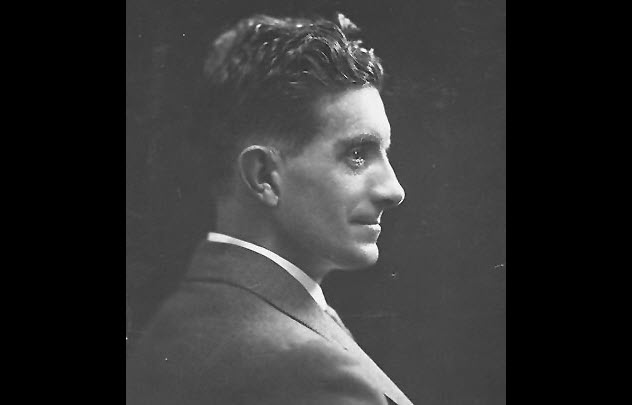

5 Jim Chee And Joe Leaphorn

In 1925, Tony Hillerman was born as a second-generation German in Oklahoma, growing up with many of his friends and classmates belonging to the Pottawatomie and Seminole tribes. After serving in World War II and working as a journalist and editor, he wrote The Blessing Way, the first book of his Navajo series, in 1970. In it, he introduced the character of Joe Leaphorn, a grizzled and cynical Navajo detective. Later, Hillerman wrote People of Darkness (1980), introducing the younger and more idealistic Jim Chee. Hillerman brought the two detectives together in 1986’s Skinwalkers. Overall, he wrote 16 novels based around his Navajo detectives. The two detectives have different perspectives on traditional Navajo culture. Chee is more accepting of the power of traditional singing and rituals, even studying to be a yataalii (medicine man) to help maintain the traditions of his people. Leaphorn has a more skeptical attitude, having studied archaeology and police procedural techniques, although he is still respectful of his ancestral culture. Although Leaphorn doesn’t believe in witches, his experience with a murder-suicide case involving a man who killed three “skinwalkers” (people who can turn into animals at will) makes Leaphorn realize that these supernatural beliefs can lead to serious problems in the real world. This dichotomy between the traditional Navajo worldview and the rationalism of detective work runs through the series. During the 1980s and 1990s, Hillerman received criticism for his portrayal of outsiders as the greatest threat to the Navajo people (with one journalist saying, “It’s the alcohol, stupid!”). Others accused him of appropriating Navajo culture for his own financial benefit. However, his novels proved popular among readers in the Navajo nation, and it soon became apparent that he was contributing a portion of his earnings to projects on Navajo reservations. He just didn’t wish to publicize it. He received the Special Friend of the Dineh Award by the Navajo Tribal Council in 1987. According to the Navajo Times, Navajo police officials have reported non–Native Americans arriving at reservation police stations asking to meet Leaphorn and Chee, oblivious to the fact that they are fictional creations.

4 Emil Tischbein

The children’s novel Emil and the Detectives was written by Erich Kastner in Weimar Germany in 1929. It followed the story of Emil Tischbein, a 10-year-old who is sent to Berlin to live with relatives by his poor, widowed mother. On the train, his money is stolen. Instead of going to the police, he chases the thief himself with the help of a number of schoolchildren. Through the assembly of a complex network of spies, couriers, and telephone communications, the children are able to apprehend the robber. An instant classic throughout Germany and the rest of Europe, the novel inspired similar works such as Enid Blyton’s The Famous Five and The Secret Seven. A film version was released in 1931. Critics praised Kastner for introducing a new form of children’s literature which took children seriously, praised their unique virtues, and sparked interest in juvenile detective literature as a genre. One critic even claimed that the novel showcased the “democratization of German civic life” and showed Berlin to be “a city in which civil liberties flourish,” which probably seemed horribly ironic only a decade later.

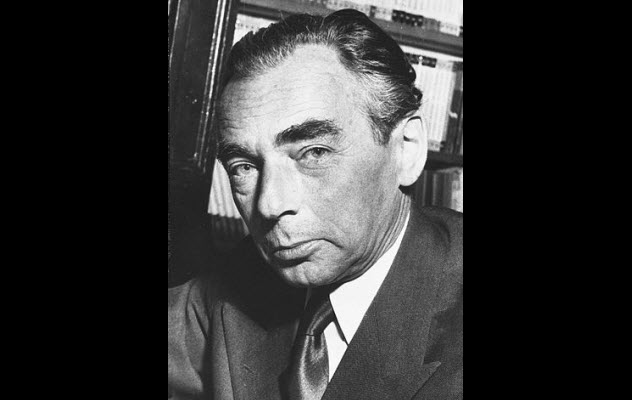

3 Hanno Stiffeniis

Michael Gregorio is the pen name of the husband-and-wife team of Michael Jacob and Daniela De Gregorio, not to be confused with the French comedian of the same name. Together, they created the character of Hanno Stiffeniis, a rural Prussian magistrate during the Napoleonic Wars who must deal with a series of strange crimes. Their first novel, A Critique of Criminal Reason, saw Stiffeniis forced to deal with a series of mysterious murders blamed on the Devil in the city of Konigsberg. Stiffeniis enlisted the help of the philosopher Immanuel Kant. Later novels involved the dogged Prussian investigator dealing with the indignities of French occupation, taking on a serial killer on the Baltic coast, and handling a vampire craze brought on by the discovery of an exsanguinated corpse. The couple used the Prussian setting because it was a distinctive place with a rich history which is gone now. The city of Konigsberg, where the first novel is set, is now Kaliningrad and home to a Russian nuclear submarine base. While the novels are based on significant historical research, the authors often invent details: “Our Prussia is a Grimm-inspired literary fantasy.”

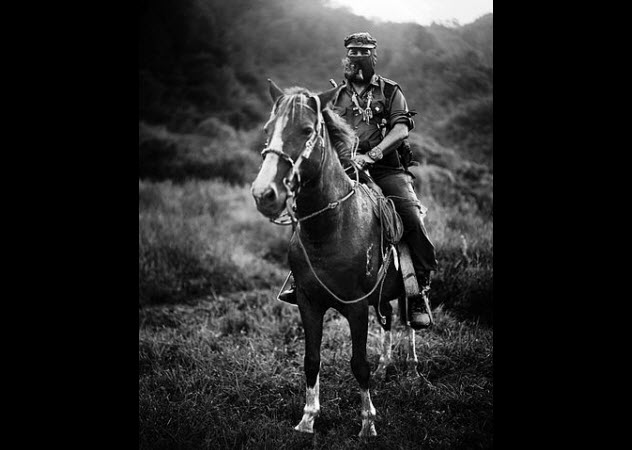

2 Elias Contreras And Hector Belascoaran Shayne

Chiapas—the poorest region of Mexico and home to the revolutionary Zapatista movement—is the setting of the Mexican detective thriller The Uncomfortable Dead. Elias Contreras is a Zapatista but also the official detective in charge of investigating a spate of missing persons reports. Despite being dead, he narrates the story. Contreras is joined by a brutal, one-eyed private detective named Hector Belascoaran Shayne. Packed with philosophical and political digressions, the novel features a rich and bewildering setting, loose plotlines, and a cast of increasingly bizarre and sometimes supernatural characters. The result is a detective story of magical realism that’s steeped in the violent history and politics of Mexico. Paco Ignacio Taibo II and Subcomandante Marcos collaborated to write this story. Taibo is a Spanish-born Mexican crime writer who has penned a series about Hector Belascoaran Shayne. Subcomandante Marcos is a writer of political polemics who is believed by many to be the pseudonym for Rafael Sebastian Guillen Vicente, who founded the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. Subcomandante Marcos only appears in public wearing a ski mask. He also brings a deformed rooster, which he says “stands for all disenfranchised people.”

1 Bony

British-born Australian author Arthur Upfield wrote a series of books from the 1920s to the 1960s involving the adventures of the half-Aboriginal detective Napoleon Bonaparte (“Bony”). The abandoned child of an Aboriginal woman and a white man, Bony was taken in by a matron at a mission station who “named him after a born leader, a man of power, of mystery, of great achievement—Napoleon Bonaparte.” An exceptional student, Bony later returns to his mother’s people and is initiated into their tribe. After helping the police solve an outback murder, he joins the Queensland police and rises to the rank of detective inspector. Bony is often an outsider, although he is accepted by Aborigines and the whites who are unaware that he is a half-caste. This isolates him from both sides but allows him to move with ease through both worlds and solve puzzles and mysteries that others cannot. Bony’s powers of deduction stem from traditional Aboriginal techniques of reading details of the land and traces left by weather, animals, and human activity. In 1970, Fauna Productions sought to remake the Napoleon Bonaparte series for TV, reasoning that a half-Aboriginal detective was a quintessentially Australian concept. The series received heavy criticism from Aboriginal groups for casting white New Zealander James Laurenson to play the lead character wearing dark makeup instead of casting an Aborigine. David Tormsen rarely has to engage in sleuthery, but when he does, he is hungover. Email him at [email protected].