In recent years, archaeologists handled fascinating rarities, some seen for the first time. Some of the skeletons displayed the ironic fate of one of history’s cruelest physicians, a weird Roman town, and duels at the bottom of a lake. Individual bones also revealed stories from prehistory, tools made from humans, and the reason why ancient women could have beaten the championship-level rowers of today.

10 The Butchered Sloth

In 2000, a farmer found bones at Campo Laborde in Argentina. They belonged to an extinct species of sloth. This was not the modern kind that hangs on a branch all day. Megatherium americanum weighed over 4 tons and stood 3 meters (10 ft) tall. Archaeologists found evidence, including a butchering knife, that the animal had been hunted and slaughtered at the site. Although it was suspected that humans preyed on giant sloths, Campo Laborde presented the first proof. Additionally, the sloth’s age was important. It belonged to a group of ultra-large mammals called megamammals. Around 12,000 years ago, about 90 percent died out. The wave of extinction was epic, sweeping through all the continents except for Africa. When dating techniques placed the sloth at 9,700 to 6,750 years old, it appeared that the species had managed to escape the die-off. In 2016 and 2017, the bones were redated with more sophisticated equipment. The new date of 12,600 years old suggested that sloths got crushed with the rest and humans were among the factors that drove the wave.[1]

9 Epic Pig Roasts

In 2019, a study was released about pigs that failed to survive barbecues. The swine in question lived in Britain during the Stonehenge era (2800–2400 BC). When researchers analyzed the bones, they found something unexpected. The fact that pork roasts happened at ceremonial sites around Stonehenge is old news. Leftovers at places like Durrington Walls and Marden proved that the epic feasts happened, but the new study wanted to know where the pigs came from. In turn, this would reveal more about those who owned them. For a long time, it was assumed that the animals started out as local piglets. Nobody truly believed that pig drives were possible, as was done with cattle over a long distance. However, when the barbecued bones were analyzed, results showed that the vast majority of pigs were born elsewhere, including Scotland and Wales. Researchers were never sure of the barbecues’ true purpose, but this gave a strong clue. The feasts tightened the social networks from all over the island. Since the pig drives demanded considerable effort, researchers believe that these meetings—and pork—were important to those who attended.[2]

8 The Speared Rib

There is plenty of evidence that people grazed on mammoth meat. However, there was no direct evidence of hunting. Head-scratching theorists suggested that ice age tribes trapped the animals or drove them off cliffs. These were likely scenarios considering that mammoths were not exactly sheep-sized. In 2002, researchers rooted around in a mammoth bonanza. Over the years, Krakow, Poland, had churned out around 110 mammoths. Among the remains, aged between 30,000 and 25,000, was a rib. Stuck in the bone was a flint fragment. Despite what it suggested, the bone was not properly analyzed until 2018 when it became the first proof that mammoths were hunted with weapons. The flint belonged to the tip of a light spear called a javelin. Measuring 7 millimeters (0.3 in) long, the depth showed that the weapon was thrown with immense force. Even so, it was not the death blow. Other hunters were probably present and brought the animal down with more spears.[3]

7 Surprising Iberian Ancestry

The Iberian Peninsula was the ancestral melting pot for modern-day Spain and Portugal. During a recent study, scientists analyzed the bones of almost 400 ancient Iberians. Together, the skeletons represented 8,000 years’ worth of genetic information. The goal was to chart when the different cultures arrived and mingled. This history turned out to be unexpectedly complex, but most surprising was a migration that occurred 4,500 years ago. The genes they brought were not unknown. They hailed from the steppes near the Caspian and Black Seas. There is an old “Steppe Hypothesis” supporting the notion that these people spread to Asia and Europe at the same time. The study of the 400 skeletons showed that the steppe people—mostly men—also made it to the Iberian Peninsula. They had a massive impact on the region’s genetics. By 2000 BC, their male Y chromosome had nearly replaced everyone else’s. Additionally, they might have brought bronze as the region’s Bronze Age began when the first steppe genes appeared in Iberians around 2500 BC.[4]

6 Human Bone Tattoo Kit

Archaeologists cannot always identify artifacts. This was the case with ancient tattoo equipment. Only from 2016 onward did a few oddities reveal themselves as inking tools. This included volcanic glass from the Solomon Islands, turkey bones from Tennessee, and cactus spines from Utah. In 1963, the same thing happened. A set of four small combs was found on the island of Tongatapu in Tonga. At the time, their purpose was unknown. The kit was placed in storage at an Australian university but was assumed to be lost after a fire. In 2008, the combs were found intact. Analysis identified seabird bones as the material used to make two of them, while the rest were crafted from human remains. The tests also gave the kit’s age as 2,700 years old, placing it among the oldest in the world.[5] There is good reason to believe that the combs were used as tattoo “needles.” When Captain James Cook wrote about tattooing in 18th-century Tonga, he described a similar bone tool used to insert color under the skin.

5 The Deviant Cemetery

Roman burials placed the deceased on their backs with the bodies neatly arranged. Valuable grave goods were often placed inside the caskets. For burials done differently, archaeologists have an interesting term—“deviant” graves. In every third or fourth Roman cemetery, one can expect to trip over one deviant. In 2019, archaeologists investigated an area earmarked for construction in Suffolk, England. Great Whelnetham used to be a Roman settlement, but it was long assumed that the region’s sandy soil could not preserve any bones.[6] Incredibly, they found a pristine fourth-century graveyard. Even more startling was the high number of deviant burials, 35 out of 52. Men, women, and children were all decapitated. Some heads were missing, while others were next to the bodies or at their feet. Since the skulls were removed neatly after death, archaeologists doubt that these people were executed. Instead, the locals probably had a reason for burying family in a way not normal for Romans. It remains a mystery why this town was different.

4 The Unlaid Egg

In 2018, paleontologists examined a fossil. The bird had been discovered in northwest China a few years earlier. The new species, Avimaia schweitzerae, was around 115 million years old. In a fossil first, the bird was pregnant with an egg. In some places, the shell had as many as six layers. This could be why the hen died. In modern birds, trauma can delay a female from nesting. Her body retains the egg and wraps unnecessary layers of shell around it. Known as “egg binding,” it smothers the embryo and often kills the mother. Finding reproductive disorders in a fossil is great, but the skeleton might also include a medullary bone. This is the holy grail for scientists obsessed with bones and bird pregnancy. When a bird prepares for egg-making, she stacks up on calcium in the medullary—something that has never been positively identified in a fossil bird. Avimaia‘s medullary region showed all the right signs. If confirmed, it would provide a unique link between avian reproduction and this bone.[7]

3 Ancient Women’s True Strength

In 2017, researchers compared the arms of prehistoric and modern women—a scientific first. The ancient group included skeletons from Europe’s Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages (5300 BC–AD 850). The living women included sedentary individuals and athletes from Cambridge, including champion rowers. The arm and leg bones were scanned and then checked for signs of physical activity. Labor intensity as well as physical strength can be gleaned from the shape and density of a bone.[8] The study revealed something remarkable. Previous studies were more male oriented, and female leg bones that were analyzed showed strength that varied. (The latter also held true in the 2017 study.) For this reason, the real arm strength of prehistoric women remained hidden. However, the scans showed that the older gals had arms stronger than elite rowers. The toughness resulted from rigorous manual labor that lasted for thousands of years, proving that women contributed extensively when people switched from being hunter-gatherers to farmers.

2 Fish That Hunted Pterosaurs

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles. During the dinosaur age, they were the top aerial predator. However, in 2012, scientists found a remarkable example of predation on pterosaurs. A lake once existed in Bavaria where the smaller fish attracted pterosaurs and the flying reptiles attracted bigger fish. When researchers examined the site, they found five drowned pterosaurs, aged around 120 million years old. They belonged to the same species, the long-tailed Rhamphorhychus. Each skeleton had a wing near or inside the mouth of a large fish. The latter also belonged to a single species, an armored fish called Aspidorhynchus that measured 65 centimeters (25.6 in) long. A closer look suggested that all the creatures died during similar duels. In every case, Aspidorhynchus probably lurched through the surface to grab a low-flying pterosaur by the wing. It was a mistake. The reptiles were too large to swallow, and Aspidorhynchus‘s abundant teeth got caught on the wing membrane. The struggle to get free would have exhausted both to the point of collapse. They sank to the bottom where low oxygen levels suffocated the fish and drowned the reptile.[9]

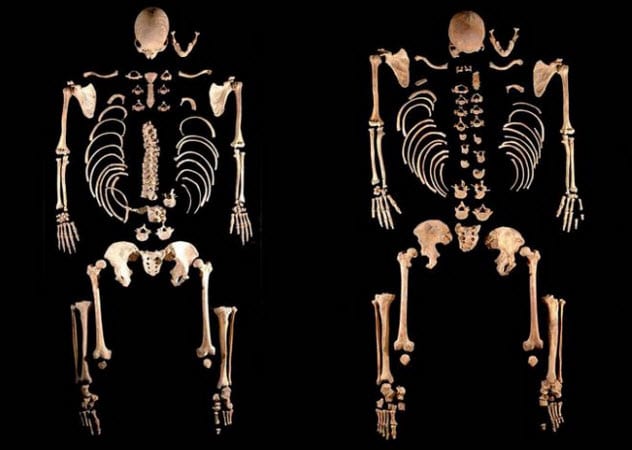

1 Mengele’s Skeleton

After World War II, Josef Mengele became synonymous with the horrors of Auschwitz. As one of the Nazi doctors who worked at the infamous concentration camp, his thirst for knowledge drove him to experiment on prisoners. Mengele killed so many people that he became known as the “Angel of Death.” His crimes made him a wanted man, but he eluded international efforts to capture him for almost 40 years. In 1979, Mengele died in Brazil. His remains were exhumed in 1985, and DNA analysis in 1992 confirmed the physician’s identity. However, his family refused to bring the body back to Germany, and the bones were stored at Sao Paulo’s Legal Medical Institute. Pathologist Daniel Munoz was among the experts who helped identify the body. Munoz, who was also a lecturer at the medical school of the University of Sao Paulo, recently realized that the skeleton could be used in the classroom. The result was ironic. This time, Mengele became the object of those seeking medical knowledge from somebody without their consent. These days, his skeleton teaches students how to find and match forensic details on bones with the person’s records.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages