10 Planet Of The Apes

You’ve seen the scene: George and Nova flee from Ape City and discover the ruins of the Statue of Liberty partially buried by the beach. It’s an iconic moment in film history wherein both the viewer and the protagonists realize that the apocalyptic world of the apes is actually Earth in the future. The movie is loosely based on a novel by Pierre Boulle, in which the Planet of the Apes is, indeed, its own distinct planet. At first, the creative team behind the movie was going to stick with that idea, but not everyone was onboard. “It doesn’t work, it’s too predictable,” said producer Arthur Jacobs.[1] He was eating lunch at a deli with Blake Edwards, who was, at one point, the director of the movie. “What if he was on the earth the whole time and doesn’t know it, and the audience doesn’t know it,” Jacobs continued. Blake was immediately intrigued. “That’s terrific. Let’s get a hold of [the writer].” They later told Boulle, who loved the idea, saying it was more creative than his own ending. But the inspiration for the iconic shot came from the deli itself. “As we walked out, after paying for the two ham sandwiches, we looked up, and there’s this big Statue of Liberty on the wall of the delicatessen. We both looked at each other and said, ‘Rosebud,’ ” referencing the key to the plot of Citizen Kane. And thus, the iconic shot of the ruins of the Statue of Liberty was born.

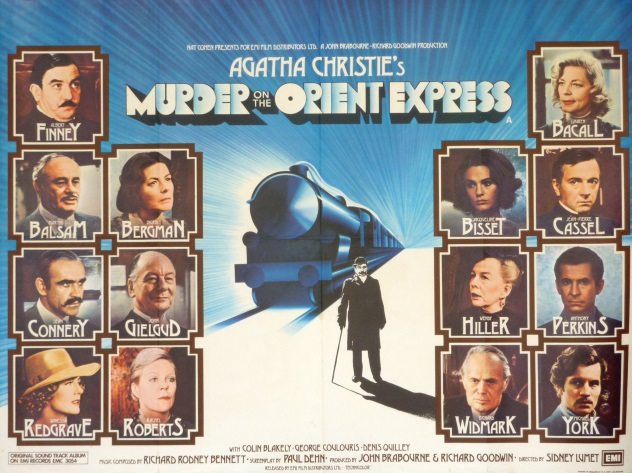

9 Murder On The Orient Express

Agatha Christie’s 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express was inspired by two real-life events: the abduction of Charles Lindbergh’s son and the six-day marooning of the actual Orient Express in a blizzard. The Orient Express had a special place in Christie’s life; she used it to escape after her first marriage fell apart, spent part of the honeymoon for her second marriage on it, and traveled frequently via the Orient Express with her second husband. Since a terrible adaptation of one of her novels in the 1960s, Christie had refused to allow any more movie adaptations. When MGM proposed an adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express featuring Miss Marple instead of Hercule Poirot, she grew even more adamantly opposed, calling their proposed movie a “rollicking farce” and harmful to her reputation.[2] After their suggestion, she absolutely refused to sell any more films to MGM. An independent film producer named Lord Brabourne had become very successful in the 1970s, and he took an interest in the project. Over a lunch with Christie, he attempted to win her over by explaining that the production team had located the original Orient Express in France, with plans to bring it to England and restore it for the movie. He also outlined an international and acclaimed cast list and described his intentions to stay faithful to the original book. Christie agreed to let him make the film. The movie was made in just 42 days, and a luckily timed snowfall created the perfect atmosphere in which to film. The producers gave Christie an advance screening, scared to invite her to the premiere, given her reputation for blunt honesty. Fortunately for them, she loved it, calling it “delightful,” and was therefore invited to the premiere. It was the last public event Christie attended. Though confined to a wheelchair, she insisted on standing to greet the queen. The film was critically acclaimed and won several British Film Awards and Oscars. Christie, however, was unsatisfied with one crucial detail: Poirot’s mustache, as depicted, didn’t live up to her description of “the finest [mustache] in England.”

8 The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense was conceived and written by M. Night Shyamalan. It established him as a writer and director and cemented his reputation as the king of surprise endings. The shoots he runs are almost as weird as the films themselves. While shooting The Sixth Sense, Toni Collette continually woke up in the middle of the night at repeating times, such as 1:11 AM or 4:44 AM, and Bruce Willis DJed in his free time. The twist ending to the movie has shocked audiences over the years with the revelation that Malcolm Crowe, the therapist who has been working with the young boy Cole, is dead. However, the waves this film made and the reputation it established for its director were almost quelled. David Vogel was Disney’s president when Shyamalan was coming up with The Sixth Sense and was attempting to regain creative control of the studio after some shifts in leadership. He purchased the rights to The Sixth Sense for $2.25 million the day he read it, without bothering to consult any of the Disney higher-ups. Vogel’s bosses were livid. They couldn’t take back Vogel’s promise to Shyamalan, but they did demand that Vogel give up some of his creative control. When Vogel refused, he was fired.[3] The cast was also almost completely different from what we know today. Bruce Willis was only involved because he was forced to sign a three-movie contract with Disney after he ruined a different movie by firing the director and crew three weeks into production, causing a $17.5 million loss for the company. Michael Cera originally auditioned for the role of Cole, but unaware that it was a movie about seeing dead people, he read his role happily and optimistically, turning Cole into a bright, normal boy.

7 The Usual Suspects

A bloodbath on a ship. Two survivors. A wild story filled with twists and turns. The Usual Suspects is a film that has a simple premise which snowballs to create an intricate and confusing plot. The original conception of the film came from a single visual image conceived of by director Bryan Singer: criminals in a police lineup. It came to him after reading an article in Spy magazine titled “The Usual Suspects,” referencing the line, “Round up the usual suspects,” from Casablanca. When asked what a movie based on this image would be about, Singer responded, “I guess it’s about . . . the usual suspects. The guys who always get arrested for some type of crime. I figure they meet in a police lineup and decide to work together.” Christopher McQuarrie, the writer, took the initial concept and ran with it, creating the ultimate plot twist in which the meek and unsuspecting Verbal Kint turns out to be the legendary crime boss Keyser Soze. The production team was so concerned with keeping the plot twist a secret that they convinced every actor that their character was secretly the notorious Soze.[4] They even used multiple actors for the flashback scenes involving Soze so as not to reveal his true identity. However, despite the intensive planning and thoughtfulness that went into the making of the movie, The Usual Suspects was met with mixed reviews. Roger Ebert hated it. “To the degree that I do understand, I don’t care,” he wrote, putting the movie on his Most Hated list. However, many others loved and acclaimed the film; it won Oscars for Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor.

6 Psycho

Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel Psycho was loosely based on the story of the Butcher of Plainfield, also known as Ed Gein. He was a murderer and grave robber from Wisconsin who had a domineering mother whose memory loomed large in his life, especially in his shrine to her and his obsession with dressing up in women’s clothes. Alfred Hitchcock wanted to transform Bloch’s novel into a movie, but Paramount Pictures called the book “too repulsive” and “impossible for films.” Unfazed, Hitchcock made the film through his own studio, Shamley Productions. Watch this video on YouTube Throughout production, Hitchcock was careful to make sure the end of the movie wasn’t spoiled. He had his assistant buy up copies of the book to keep its twists and turns a surprise. However, after the movie was released, it gained such popularity that the spoiler became quickly and widely known: Norman Bates had developed an alternate persona in which he took on the personality of his mother and murdered young women. Since then, Psycho has become emblematic of both Hitchcock and horror, with both the movie and its twist earning an important place in cinematic history.[5]

5 Shutter Island

Like many others on this list, Shutter Island’s story was first introduced to the world as a novel. Dennis Lehane visited Boston Harbor’s Long Island with his uncle when he was a child during the Blizzard of 1978. Drawn in by its secluded nature, he became curious about what would happen if people were stranded on that island during a storm, without the use of modern technology. He also set out to create his own unique style, blending classic gothic literature with pulp and B movies to create his novel. “I had a hybrid of the Bronte sisters and Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers in mind,” Lehane said. The process of turning the book into a movie wasn’t a simple one. “Since I’d not really worked in thrillers before, it necessitated I do an outline where I could track where the reversals were and where each moment could go,” screenwriter Laeta Kalogridis said.[6] She created a 50-page outline before even attempting to pen a word of the script. Lehane was ultimately happy with the movie but did admit that watching it was a weird experience. “Those are your lines, but they’re not,” he said. “That’s your world, but it’s not really. Those are your characters, but they’re not quite. It’s all interpretative.” And as for the spoiler itself? Well, that’s one we’ll leave intact. You’ll have to watch the movie (or read the book) to see for yourself.

4 Fight Club

Fight Club started as—you guessed it—a novel. Chuck Palahniuk’s book came out in 1996 and inspired the hit movie that had audiences everywhere questioning a culture filled with violence and consumerism. The book stemmed from a germ of an idea Palahniuk had as a volunteer in a hospice, where he would take people to and from support groups. “I found myself sitting in group after group feeling really guilty about being the healthy person sitting there—‘The Tourist.’ So I started thinking—what if someone just faked it? And just sat in these things for the intimacy and the honesty that they provide, the sort of cathartic emotional outlet. That’s really how that whole idea came together.” Watch this video on YouTube The famous twist in the movie’s ending was ultimately a result of Palahniuk’s writing style and continual need for action. “I wanted fiction based on verbs, rather than a fiction based on adjectives,” he said, describing how his books are driven by his desire to have things happen. “Sometimes, [ . . . ] I get too out of control and instead of a plot point every chapter I want a plot point in every sentence.”[7] As for the work’s adaptation into a movie, Palahniuk had only praise: “Now that I see the movie, [ . . . ] I was sort of embarrassed of the book, because the movie had streamlined the plot and made it so much more effective and made connections that I had never thought to make.”

3 Casablanca

Casablanca is a classic love story, one in which the turmoil of emotions within the characters echoes the tumultuous landscape of the city during World War II. The plot revolves around Rick and Ilsa, two characters who had been in love and run into each other again many years later, Ilsa on her husband’s arm. Rick and Ilsa’s passionate reignited affair comes to its head when the two stand on an airstrip. Inside the plane waits Ilsa’s husband, safety, and the chance to continue the noble work of fighting the spread of Nazism. Outside waits Rick, passion, and danger. Ilsa is unable to make the decision between the two men and the two lives they promise. She’d previously told Rick, “You’ll have to think for both of us, for all of us.” Watch this video on YouTube Ingrid Bergman, who played Ilsa, did not know the ending of the movie when she began filming. In fact, no one did. When the project began, they only had half a script. Toward the end, scenes were being written the night before. In the final few days, scripts were being written on-set minutes before the scenes in question were to be shot. Frank Miller, author of the book about the making of the movie, Casablanca: As Time Goes By, noted that “the major issue with Ingrid Bergman was her uncertainty about how the film would end [ . . . ] she didn’t know which man would win her. [The director] kept telling her to play it ‘in-between,’ which is what she did. And it made the film work better than if she’d known the ending.”[8]

2 The Empire Strikes Back

It’s a moment that has stunned audiences across generations. Legions of Star Wars fans have sat slack-jawed as they heard the iconic line: “I am your father.” In an interview with Rolling Stone, George Lucas said, “[The movies are] really about mothers and daughters and fathers and sons. The early films are about Luke redeeming his father, so Luke’s the focus. But it’s also about Princess Leia and her struggle to reestablish the Republic, which is what her mother was doing.” And that is one of the reasons the famous plot twist is so iconic: It’s representative of the larger theme of the movies as a whole, themes that make the twist believable enough so as not to leave an audience scoffing. Indeed, the theme of parents and children is reflected in the name of the iconic villain himself. “ ‘Darth’ is a variation of ‘dark.’ And ‘Vader’ is a variation of ‘father.’ ” Lucas revealed. “So it’s basically ‘Dark Father.’ ”[9]

1 Citizen Kane

“Rosebud.” It is one of the most iconic film quotes, from the movie whose name has become synonymous with the idea of a classic. “Rosebud” is the last word of newspaper magnate Charles Foster Kane before his death, and a reporter’s search to decipher its meaning is at the root of the movie. As the audience is taken through the life of Citizen Kane, the man is deeply examined, though the meaning of his final word becomes no more clear. It remains a mystery until the final moments of the movie, when Kane’s childhood home is being cleared out. We see his childhood sled being thrown into a furnace, and as it gets consumed by the flames, we see the name of the sled: Rosebud. The screenplay was a collaboration between Orson Welles, who starred in the movie as Kane, and screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz. Rosebud was Mankiewicz’s idea, and Welles was quick to deny credit for it. “It’s a gimmick, really, and rather dollar book Freud,” he said of the whole affair. Gore Vidal had a story that seems to confirm the lack of true meaning in the word “Rosebud,” claiming that “Rosebud” was Randolph Hurst’s nickname for his mistress’s clitoris, and Mankiewicz put it in the movie as a private joke. Frank Mankiewicz, Herman Mankiewicz’s son, could not let that story stand: “It is time Vidal’s story be put to rest and the truth be told,” he said. “Rosebud was a bike. It was my father’s bike.”[10] Rosebud was the name of a bike Mankiewicz had owned when he was little. It was stolen from him while parked outside a public library. As punishment for his carelessness, Mankiewicz’s parents refused to buy him a new one. Rosebud, as a bike or a sled, stolen or burned, remains to this day an emblem of childhood innocence and happiness.