10There Are Different Types

We hear most about the bubonic plague, but that’s actually just one of three plague varieties. The bubonic plague is distinguished by swollen lymph nodes, called “buboes,” which give the disease its name. This type is spread only through the bites of fleas and blood contact with the infected insect; there is no way that bubonic plague can spread from one person to another. Similarly, septicemic plague is spread only through breaks in the skin and by blood contact. It worsens as bacteria multiply in the blood stream. Septicemic plague has many of the same symptoms as bubonic plague, including fever and chills, but it lacks the bubonic plague’s telltale nodes. The third type is the only one that can transmit from person to person. Pneumonic plague is airborne and can pass from one person (or animal) to another just by breathing in close proximity to someone. The different types of plague can mutate into one another; pneumonic plague and septicemic plague are often complications of untreated bubonic plague. Because the different types have similarly devastating effects, we’ve long thought that bubonic plague was the disease that swept across Europe during the Black Death. New research supported by DNA evidence suggests the Black Death wasn’t bubonic plague after all but the faster-spreading pneumonic plague.

9It Originated In China

Researchers have successfully traced the presence of bubonic plague back to its origins in China, more than 2,600 years ago. Different strains of the plague have different bacterial structures. By looking at each strain’s distribution, researchers have traced bubonic plague backward along the Silk Road, isolating 17 different bacterial strains. All these mutations trace back to a single type of bacteria that only started spreading outside of China in the last six centuries, carried by rats on ships leaving Chinese ports. In 1409, ships carried the plague into East Africa. It also spread outward both east and west, through Europe and through Hawaii. It eventually came to the United States in the late 1800s after an epidemic swept through the Yunnan province.

8The Village That Sacrificed Itself

In 1665, a tailor from the village of Eyam in Derbyshire, England ordered cloth from London. When the delivery came, the village received much more than just cloth—it became infected with the plague, which was already laying waste to the capital. People started dying, but they knew the plague hadn’t spread to nearby villages. So, led by clergyman William Mompesson, the villagers decided to quarantine themselves, staying in the plague-stricken town to prevent the disease from spreading. The quarantine began in June 1666. From that point onward, no one could enter or leave the village. Neighboring towns left food at designated places well outside of the village proper. Pre-quarantine, 78 died, and by the end of the plague, that number climbed to 256. Before the townspeople opened their village once again to outsiders, they burned furniture and clothing, hoping to eradicate any traces of the disease that might still lie dormant. The sacrifice was a success. None of the neighboring villages had a single case of the plague. Mompesson lost his wife Katherine to the disease, but he himself survived.

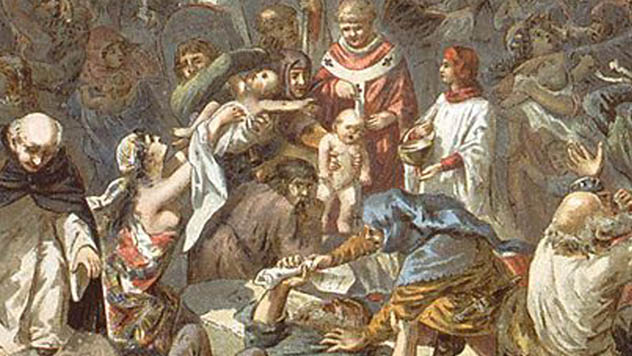

7Conspiracy Theorists Used It To Persecute Jews

With the plague decimating Europe during the 14th century, Christians and Jews started playing the blame game. An estimated 25 million people died in the first part of 1348, and a rumor soon began that the plague was a Jewish conspiracy to wipe out Christianity. Supposedly, the conspiracy had begun in Toledo, Spain and spread throughout Europe. The Count of Savoy started arresting and interrogating Jews, determined to find his version of the truth. His brutal torture elicited many confessions of responsibility, mostly people confessing to poisoning town and city water supplies. The count sent these confessions to other towns as a warning, but the people there took them more seriously. Hundreds of Jewish settlements were burned to the ground, and countless people were murdered. In Strasbourg, nobility and city authorities clashed over whether to massacre their Jewish citizens. The nobles figured doing so could remove the threat of plague and their creditors in one go. On Valentine’s Day 1349, around 2,000 Jews burned on a massive wooden platform in Strasbourg, their wealth seized and redistributed among the Christian nobles. The plague still came to Strasbourg. It took 16,000 lives.

6The Plague Wasn’t A Guaranteed Killer

Many of us imagine that the plague was a certain death sentence. That belief comes from the massive, widespread devastation the plague caused rather than its effects on individual sufferers. Many stories actually tell of people simply immune to the plague, and others record those who contracted the disease but survived. Marshall Howe was one such individual. Howe lived in the village of Eyam during its quarantine, and after recovering from the plague, he helped bury those who died from it. He was reportedly carrying one man to his grave when the corpse spoke and asked for something to eat. The supposed dead man eventually recovered. Another Eyam resident, Margaret Blackwell, recovered from the plague after being so overcome with thirst that she drank a pot of melted bacon fat. Studies of Black Death victims’ skeletal remains reveal a telling tale. Most already suffered from some other ailment, such as disease or malnutrition, before contracting the plague. The plague did kill previously healthy individuals, but it’s now thought that many who were healthy stood a chance at survival.

5A Teenage Nostradamus Became A Successful Plague Doctor

Nostradamus is today largely remembered for his vaguely worded prophecies. But in 1518, he was traveling the French countryside acting as a plague doctor—and he was a mere 15 years old. After living this way for several years, he reenrolled in university (he’d started at 14 but had dropped out to become a traveling apothecary) and earned his degree in medicine in 1522. He continued to work as a plague doctor, as he was seemingly immune to the disease himself. According to his writings, Nostradamus felt he was doing little good in treating the afflicted because his remedies only made victims comfortable rather than curing them. In actuality, he was one of the first doctors to get it right. Instead of typical medieval treatments like leeches and bleeding, Nostradamus pushed for curing the plague with cleanliness. Patients were encouraged to go outside and to get fresh air. He kept those patients and their surroundings clean and disposed properly of infected corpses. He also subscribed to the notion that the plague was caused by bad air, and he developed a spice and rose lozenge that would ease sufferers’ symptoms. At one point, he had such success curing people of the plague that he was comfortably supported by donations from individuals who lived in the city of Provence.

4It Changed World Culture

The plague’s spread left survivors in a world forever changed. It brought a new awareness of death and mortality, and the artists of the time turned to painting what they saw around them. In eras of plague, particularly the 14th and 16th centuries, art got much darker. Religious paintings often featured the dead. Hell was depicted more often than heaven—and oftentimes, it was a hell on Earth. One of the eeriest styles of art to come out of the 16th century was a change in tomb and gravestone design. Before, people were often shown at rest. Now, artists introduced the transi, a form of sculpture that more accurately showed the dead rotting flesh and skeletal form. The plague had another strange effect on the world’s art and literature, and that wasn’t just a change in content but in style and quality. When the plague struck, it attacked without heed to a person’s standing, status, or occupation. Many great masters died in the midst of teaching their proteges. That in turn led to a dynamic shift in the quality and techniques present in art from the time.

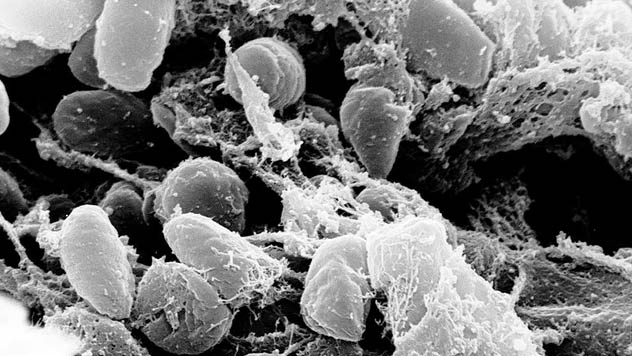

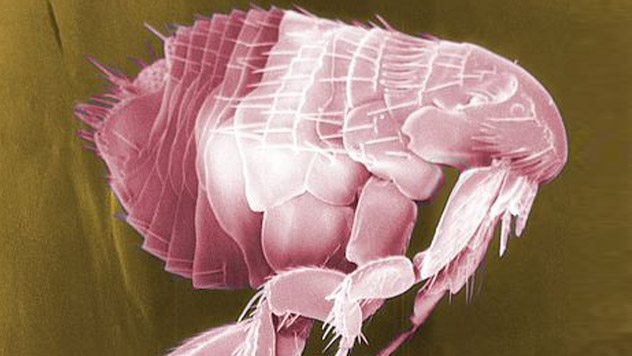

3The Plague Bacteria Starved Fleas

Bubonic plague is spread by fleas, but the whole process is actually a lot more complicated and disturbing than that description suggests. Fleas survive on the blood of animals, and so does the plague bacteria. Once a flea ingests diseased blood, the infection goes to work on the flea itself. It begins to reproduce in the flea’s stomach, living in the digestive tract of the insect and effectively blocking its digestive process. This often kills the flea, but in the meantime, it starves it. This means that the flea bites more often and looks for more animals for nourishment, spreading the disease faster than a flea with a normal life cycle. Cats and rats are particularly susceptible to the plague virus, which further helps it spread. When the flea’s usual host—rodents—start dying out in massive amounts, it seeks other hosts, pushing the disease to domesticated animals and humans. (Dogs have a natural resistance to the plague bacteria, and even if they’re bit and are repeatedly exposed, they usually don’t become sick.)

2Death-Bringing Plague Ships

As we mentioned earlier, the plague sometimes traveled from one area to another by ship, and this was actually one the quickest ways in which it spread. In 1347, Italian ships spread the plague from Constantinople to Alexandria to Marseilles and then on to Venice, Genoa, and next on to the rest of Europe. Why didn’t the trading ships just stop? Surely captains would weigh the benefits of bringing a plague-stricken crew to land against preventing the spread of the plague throughout the continent? It turns out the plague was much too sneaky to allow such precautions. It would appear on ships well before making itself known. First, it would incubate, multiply, and makes the rounds of the rat population. Then it would jump to humans, and even then, it could take up to five more days to make a person ill. A trading ship could become a death ship for almost a month before anyone on board would have the slightest idea anything was wrong. By nature, rats on a ship would largely avoid human contact. In many cases, plague-bearing fleas would find new rat hosts once ships made port or would stow away in cargo that was then taken and distributed throughout the destination city.

1Believed Causes Of The Plague

The rampant illness and the countless deaths left survivors throughout history looking for a reason for their suffering. One common idea was that mankind brought on the plague by its own evil. Supporters of this theory pointed to passages in the Bible where God used pestilence and plagues as a weapon to punish the unholy. In the Book of Revelation, Pestilence is one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and people felt that this disease surely heralded the end of the world. To the nobility and other authority figures, this idea had a practical advantage. Should the masses believe that a higher power was holding them accountable for their actions, said authorities could more easily regulate activities that they thought troublesome, like gambling and brothels. Ideas about cures for the plague were linked to possible causes. It was long thought that the balance of the humors and states of the body was crucial to staying healthy; if that was true for humans, then the same might be true for the universe. This led to a number of astrological theories on what was causing the clear imbalance of life and death on Earth. Quoting Greek philosophers and their writings on the balance of life, astrologer Geoffrey de Meaux tried to use the positioning of the planets within the zodiac to determine how long each outbreak would last, why certain cities were vulnerable, and who would die next. Read More: Twitter