10 John Henry18-Year-Old Convict

The story of railway steel driver John Henry is a testament to American grit and determination. Faced with replacement by a mechanical drill, his only option was to prove that he was better than a machine. He did—and died of exhaustion just after he proved that he could drive a spike as fast and as well as any machine. He was one of those characters from history who always seemed like a bit of a tall tale, but a professor from the College of William and Mary thinks he’s found the real John Henry. He really did work on building the railways, and he really did die laboring on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. But there’s more to the story. In the 1870s, work on the railway was done in large part by labor conscripted from the nearby Virginia State Penitentiary. In 1992, excavations at the old prison uncovered around 300 sets of remains belonging to prisoners from that era. Among the records, one name in particular stood out—John William Henry. According to the files, he was 18 years old when he was convicted of theft after stealing from a grocery store. His sentence was 10 years in prison, and when the prison started leasing their inmates to the railroad, Henry was one of them. Some intriguing evidence seems to support the idea that this was the John Henry of folklore. The ballad written about him says, “They took John Henry to the white house, and buried him in the san’.” That’s an accurate description of the white penitentiary building where he served his time. He also worked on the Lewis Tunnel in West Virginia. As historians know, steam drills were tested against human labor there. Then there’s the tragic end to the story. When steam drills first came on the scene, they often broke down. An experienced team of men could easily beat the drills but working alongside them had deadly consequences. The drills spit clouds of silicon dust into the air. By breathing in that dust, the workmen were at high risk of developing silicosis, a lung disease that quickly killed countless workers.

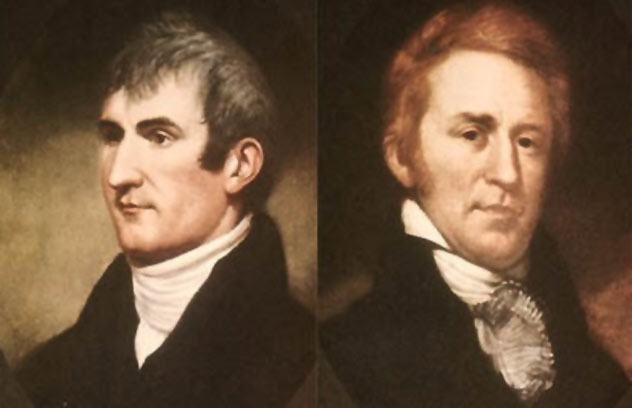

9 Meriwether Lewis And William ClarkMedical Budget

Few American explorers are as firmly entrenched in the spirit of westward expansion as Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who braved the unknown wilderness far from civilization. It was surely a noble endeavor, but a look at their medical training—and how Lewis decided to spend their medical budget—sheds a different light on the expedition. At that time, there were almost no doctors in the country. Even in New York City, a newspaper proclaimed that the city’s 40 doctors were “mere pretenders” and “entirely ignorant.” Lewis’s mother was a practicing herb doctor (aka a “yarb”), which may have given him some knowledge of herbal remedies. In preparation for the expedition, Thomas Jefferson also sent Lewis to study medicine in Philadelphia under the guidance of Declaration of Independence signer Dr. Benjamin Rush. Of his total budget, Lewis allotted about $55 (around $855 in 2014 dollars) for medicine. By comparison, he set aside $696 ($10,813 in 2014 dollars) to buy gifts for the native people they might encounter on the trip. We know what medicines were purchased for the expedition because all of them came from an apothecary in Philadelphia. Ultimately, Lewis went over his medical budget, with most of the funds spent on Peruvian bark, which was used for controlling fevers and malaria. He also bought 600 of Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills, which mainly contained laxatives. The pills did their job so well that they were dubbed “thunderbolts.” Lewis also bought 700 doses of other laxatives, like magnesia and rhubarb. Lewis stocked up on cures and treatments for venereal disease, which may have been a wise decision. During the expedition, they encountered many tribes who believed in offering their wives to white explorers as a way to absorb the strength of those explorers through sex. So Lewis’s store of questionably safe venereal disease treatments—including mercury pills—came in handy. He also brought along one clyster syringe, which was designed for enemas and for alleviating the symptoms of gonorrhea by flushing out the urethra.

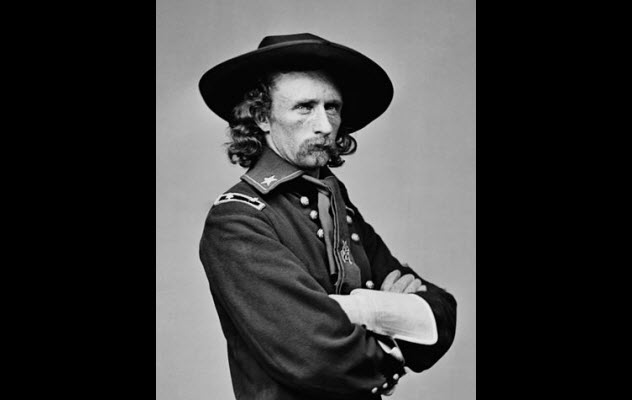

8 General George Armstrong CusterHorse Thief

Best known for losing the Battle of the Little Bighorn, General George Armstrong Custer was recently outed as a horse thief, too. At least, that’s what documents from the National Archives and the library of the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument suggest. In the months after the Civil War, Union troops were openly seizing Confederate horses, mostly for military purposes. But Custer’s involvement with the thoroughbred bay stallion Don Juan was more than a military seizure. Custer wanted to profit from the horse, and he stopped at nothing to take the animal from the real owner, Richard Gaines. Throughout the South, Don Juan had a reputation as a valuable racehorse, estimated to be worth about $10,000 in 1865 (about $153,000 in 2014 dollars). Technically, Custer bought the horse from the US military for $125. But he also had a pedigree for Don Juan, which wouldn’t happen with a horse seized through standard military procedures. In a letter from that time, Custer asked his father-in-law to keep secret how little Custer had paid for Don Juan. He also detailed his plans to profit from the war by selling the horse for thousands. However, he couldn’t do that without the pedigree. But his possession of the pedigree proved that the horse was not a military seizure. So Custer’s story about buying the horse after a military seizure didn’t make sense. Gaines was vocal about his claim to the horse, which had been taken from his groom by soldiers who had demanded both the horse and the pedigree. Within two weeks, Custer used his military clout to possess the horse and the paperwork. The matter went as high as Ulysses S. Grant, who ordered Custer to return Don Juan to his rightful owner as it was a clear case of abuse of power and theft. However, General Philip Sheridan testified that the horse was simply taken for military use by Union troops. Custer established ownership of Don Juan with some public appearances, while any shady dealings were swept under the carpet. After he showed off the animal at the Michigan State Fair in 1866, Custer prepared to sell him. But karma kicked in, and the horse died a month later after a blood vessel burst.

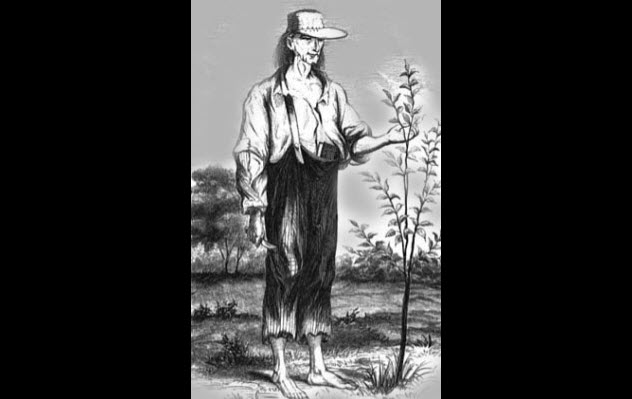

7 Johnny AppleseedTrue Mission

In school, we all heard the story of Johnny Appleseed (whose real name was John Chapman), the kindly man who wore a tin pot for a hat and walked across the country planting apples. Although it’s true that Chapman planted apple trees throughout the country, he didn’t do it for eating purposes. He actually did it for alcohol—and profit. Trying to get settlers to move west, the government promised each settler a patch of land. However, families had to prove they were going to stay and improve the property. One way to do that was to plant 50 apple trees. But that was hard work, and the trees had to be planted within a certain time frame. So many families chose to outsource the work to John Chapman. But it was against Chapman’s religion to plant and graft trees that produced apples that were good for eating. Instead, Chapman’s trees yielded small, sour apples which were great for making hard cider. For years, his apple trees formed the backbone of America’s alcohol production, which didn’t fall out of fashion until government agents took axes to the trees during Prohibition. However, the American tradition of making cider has made a comeback recently, and so have Chapman’s trees. Cuttings from Chapman’s last tree, found on the Harvey-Algeo Farm of Nova, Ohio, have been grafted onto other apple rootstock and replanted.

6 John BrownDomestic Terrorist

Usually called an “abolitionist,” John Brown led the failed raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 to secure weapons for an armed slave revolt in the fight for freedom. Seventeen people died that night. Although his ideals sounded noble, his methods horrified as many Northerners as Southerners. Born in Connecticut to an extremely religious family, Brown suffered many tragedies. His mother died when he was young, his first wife died in childbirth, and nine of his 20 children died before him. At age 55, Brown finally found his calling, guerrilla warfare in the name of abolitionism. After states were given the right to choose whether they would allow slavery, Kansas turned into a battlefield. Brown moved there to better wage his own brand of war. In May 1856, proslavery fighters sacked the town of Lawrence. Although only one person died—a proslavery man killed when a brick fell on him—Brown decided to seek retribution. Dubbing themselves the “Army of the North,” he and seven other men (including four of his sons) headed into proslavery Pottawatomie Creek a few nights later. The group stormed homes and killed indiscriminately. Dragged into the streets, their victims had their heads hacked to pieces with broadswords before they were shot. By the end of the night, five were dead. Although Brown didn’t do the killing, he decided who would live and who would die. With Brown becoming a strange mix of abolitionist hero and wanted fugitive, the Pottawatomie massacre kicked off a wave of violence that left about 200 people dead by the end of the year. When Brown was sentenced to hang after Harpers Ferry, he received a letter from the wife and mother of three victims killed by Brown’s men at Pottawatomie Creek. She wrote: With the loss of your two sons, you can now appreciate my distress, in Kansas, when you then and there entered my house at midnight and arrested my husband and two boys and took them out of the yard and in cold blood shot them dead in my hearing, you cant say you done it to free our slaves, we had none and never expected to own one, but has only made me a poor disconsolate widow.

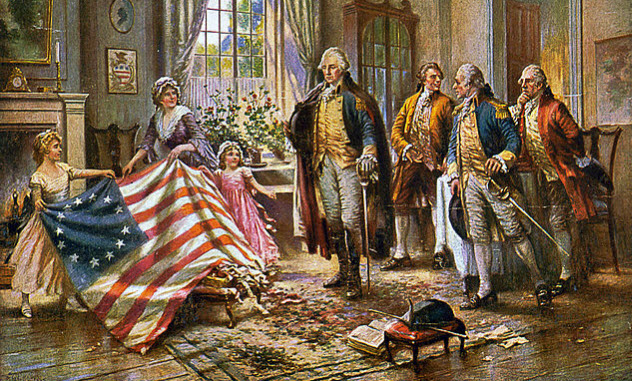

5 Betsy RossPossible Role In The Revolution

Betsy Ross has one of the biggest roles in American myth and folklore as the supposed creator of the first American flag. Although this story didn’t appear until 1870, it’s firmly cemented in the public consciousness. Sadly, it’s a myth that may obscure her more interesting role in the revolution. When George Washington made his famous Christmas Eve crossing of the Delaware River in 1776, it was the beginning of the capture of Trenton. That victory might not have happened if 2,000 soldiers had been on guard that night as they were supposed to be. Instead, their Hessian commander, Carl Emilius von Donop, delayed his troops in Mount Holly because he was infatuated with a young widow in town. That young widow is rumored to be Betsy Ross. Her husband, John Ross, had recently been killed while on guard duty for the colonists. The Rosses were friends with the Washingtons, and Betsy’s work for the revolution was well-known. Although she may not have designed the flag, she did sew uniforms. It’s also possible that she used her feminine wiles to delay von Donop and his 2,000 men as her friend marched on Trenton. It’s just a theory supported mostly by a circumstantial connection between Betsy Ross and Mount Holly, but historians are interested in the idea. Whoever the widow was, she may have played a crucial role in one of the most infamous battles of the American Revolution.

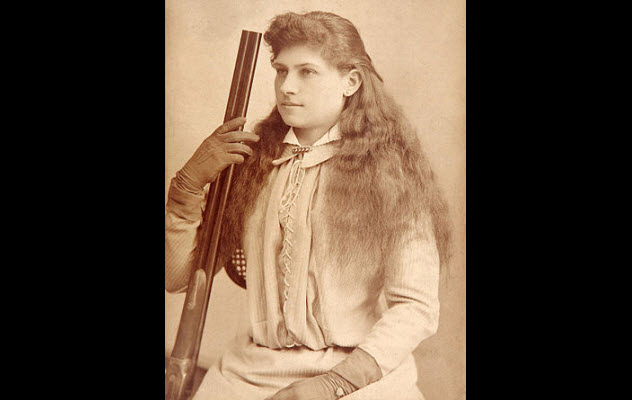

4 Annie OakleyAlleged Cocaine User

Born in 1860, Annie Oakley had all but retired from the public eye as one of the West’s most famous sharpshooters by 1901. The best at what she did, Oakley was always the product of a carefully groomed reputation. For example, she was rarely, if ever, shown killing animals in her shooting stunts, and she was always dressed like a proper Victorian lady. So when William Randolph Hearst ran a story saying that Oakley had been caught stealing to fund her cocaine habit, the country loved it. The story went turn-of-the-century viral, running in 55 papers across the country before the perpetrator was revealed to be a burlesque dancer of questionable morals who had billed herself as “Any Oakley.” In days, the bogus tale destroyed an image that Oakley had worked a lifetime to create. But she sued each newspaper for libel, traveling across the country and winning or settling 54 out of the 55 cases. It took seven years, and in the end, her defense was so expensive that she lost money despite receiving large monetary settlements. If Oakley hadn’t fought back, Hearst’s story had the potential to change the way America remembered one of the most well-known female shooters in history. In the middle of the fight, Hearst even hired some private investigators to dig up dirt he could use against her. When they came back with nothing, he—and his newspapers—were forced to pay up and admit that Oakley didn’t have a cocaine habit after all.

3 Daniel BoonePolitical Career

Daniel Boone was one of the great American frontiersmen, but he was also a politician who served several terms in the Virginia General Assembly. In particular, one incident suggests that he didn’t always put his country first. In 1781, Lord Cornwallis was moving his troops closer to the legislature’s headquarters in Richmond. It was only a heroic—and often forgotten—overnight gallop by Jack Jouett that enabled the American heads of state to escape the British . . . for the most part. According to the memoirs of Boone’s son Nathan, Jouett and Daniel Boone stayed behind to salvage some of the young government’s papers. As they were loading those papers onto a wagon, they were captured by British forces. Strangely, Boone and Jouett were released after only a few days in British captivity. No one’s sure why they were released, but Boone followed the rest of the General Assembly to reassume his position there. One theory suggests that Boone promised not to fight the British in exchange for the safety of his family. While it’s known that Boone’s wife had relatives fighting for the British, she may also have had family members serving in the unit that captured Boone and Jouett. Another theory says that Jouett fled the scene, wearing full military gear and luring the British away from Boone and potentially dangerous documents. Whatever Jouett’s role was, he did receive an official commendation from the General Assembly, presented with a set of pistols and later a sword as acknowledgment of his “activity and enterprise.”

2 Molly PitcherTruth vs. Myth

One historian found the story of Molly Pitcher repeated as fact in 18 of 22 history textbooks, with most reinforcing the idea that her real name was Mary Hayes. Other versions call her Mary Ludwig, but the story is always the same. During the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, she carried pitchers of water to the fighting men on the front lines—hence the nickname. When her husband collapsed by his cannon, Molly supposedly dropped her water, gathered her skirts, and stepped into his place. There’s also an anecdote about a cannonball that passed directly between her legs without fazing her in the least. For her actions, she was supposedly made a captain (or perhaps a lieutenant) by George Washington. However, there’s no evidence to suggest that this story is true. A woman stepping onto the front lines and helping to win the battle was never repeated in any contemporary papers. The first mention of Molly Pitcher didn’t come until 50 years later, when the story finally began cropping up in print. However, the story likely evolved from a different woman in a different battle. Mary Corbin, affectionately referred to as “Captain Molly,” did fire a cannon for her husband after he was killed. The incident happened two years earlier at Fort Washington, not the Battle of Monmouth. Another woman named Moll Pitcher shows up in history at about the same time. However, she was a fortune-teller who was regularly consulted by sailors trying to determine whether to begin their journeys. The merging of the stories seems to have happened between 1830 and 1840.

1 Black BartHorse Phobia

Charles Boles (aka “Black Bart”) was a notorious stagecoach robber in the Wild West. Between 1875 and 1883, he supposedly targeted at least 29 Wells Fargo stagecoaches, escaping with thousands of dollars. Despite being a Civil War veteran and a successful thief, he was actually a bit of a coward. Boles conducted all his stagecoach robberies without a key piece of equipment: a horse. He was absolutely terrified of them. All his holdups and getaways were on foot. He also hated the sight of blood, regardless of whose blood it was. For all his successful robberies, there were several from which he ran. In November 1880, a planned robbery on the Oregon border went bad when the driver pulled out a hatchet. Boles had a rifle, but the driver’s threats and the sight of the hatchet sent him fleeing for the hills. In July 1882, a veteran messenger whom he attempted to rob took a shot at him, knocking off his hat and grazing his head. That incident also sent him running. His absolute hatred of horses and bloodshed has never been satisfactorily explained, but it may have something to do with his wartime service. Boles was wounded three times in battle, receiving commendations and promotions for his service. Often called one of the great “gentlemen robbers” because he refused to hurt his targets or take money from anyone except Wells Fargo, that image fades when you look at his personal life. After marrying in 1854 and having three daughters, Boles left his family to serve in the Civil War. When he returned, he stayed just long enough to have another son. In 1867, Boles headed to Montana alone to try his hand at gold mining. Eight years later, he briefly visited his family during his robbery career. After abandoning his wife and children again, he attempted to reconnect with them while he was in prison. Even though his letters profess his love and devotion for his wife and family, he didn’t return to them when he was released from jail. Read More: Twitter