But fantasy wasn’t born the day Middle-earth was first created. Tolkien himself drew inspiration from older works, as well as his close friend and fellow author C.S. Lewis. In fact, the two once planned a collaboration that Lewis began working on.[1] Here are ten tales that inspired Tolkien in his own work and gave birth to the legendarium we know and love.

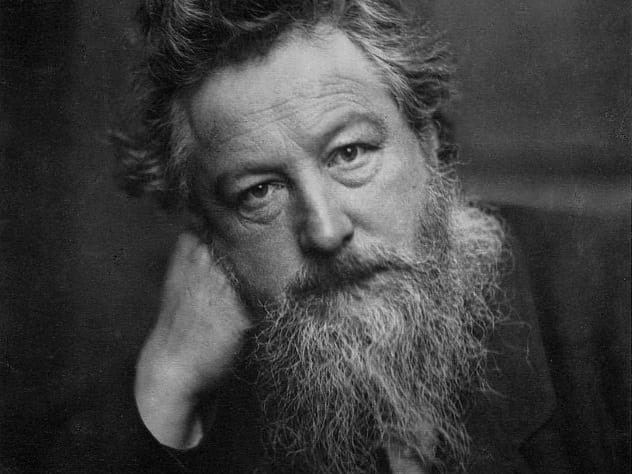

10 The Roots Of The Mountains By William Morris

One of Tolkien’s favorite stories as a child was The Story of Sigurd. This came from The Red Fairy Book by Andrew Lang. More on that later, though. Right now, it is the anthology’s preface that we want to look at. There, Tolkien was introduced to the name William Morris, as The Story of Sigurd was actually a shorter version of Morris’s The Volsunga Saga, which he had translated from Old Norse. William Morris was a very important influence on the professor while growing up, though not many of his biographers have mentioned it. Tolkien attended King Edward’s School in Birmingham from 1900 to 1911. While there, he was introduced by his form master to an English translation of the Anglo-Saxon tale Beowulf (which will also come up later). Nobody knows for sure anymore, but some scholars think that this translation was by Morris and A.J. Wyatt. In 1911, during his senior year, Tolkien read a paper about the Norse sagas to the school’s Literary Society. And a few months later, he published a report about The Volsunga Saga in the school’s chronicles. In it, he used the name of a translation by Morris, as well as words and phrasings that echoed Morris’s own. Years later, in 1920, Tolkien read his essay “The Fall of Gondolin” to the Exeter College Essay Club. The club president wrote in the minutes that Tolkien was following a tradition “in the manner of such typical romantics as William Morris.” Even though there is a lot of evidence of Morris’s influence on the professor, very few scholars have talked about it so far. Maybe it’s because Tolkien only seems to have mentioned this influence once, in a letter to Professor L.W. Forster in 1960. Speaking of the Dead Marshes, Tolkien wrote that, “They owe more to William Morris and his Huns and Romans, as in The House of the Wolflings or The Roots of the Mountains.”[2] But it’s become clear that The Roots of the Mountains was the foundation upon which Tolkien built his own mythology of Middle-earth.

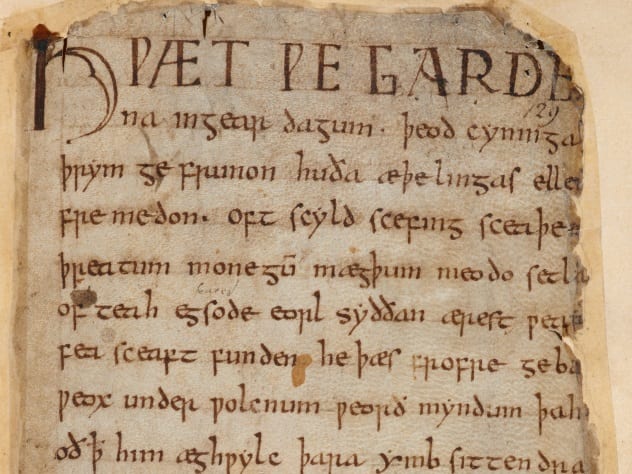

9 Beowulf

This story was so important to the professor that he changed the way we think about it. In 1936, Tolkien wrote an essay called “Beowulf : The Monsters and the Critics,” where he said that it was important as literature. Thanks to Tolkien, we now see Beowulf as a part of fantasy’s foundation. Its theme of light vs. dark has become the theme of modern fantasy, including Tolkien’s own stories. Tolkien didn’t think that the dragon in Beowulf was “frightfully good,” as he told Naomi Mitchison in a letter he wrote in 1949. But the story was near the top of his list. In 1938, the professor told the Observer that, “Beowulf is among my most valued sources.”[3] John Garth, who wrote Tolkien and the Great War, even said, “If you took Beowulf away, Tolkien would not be the writer he became.”

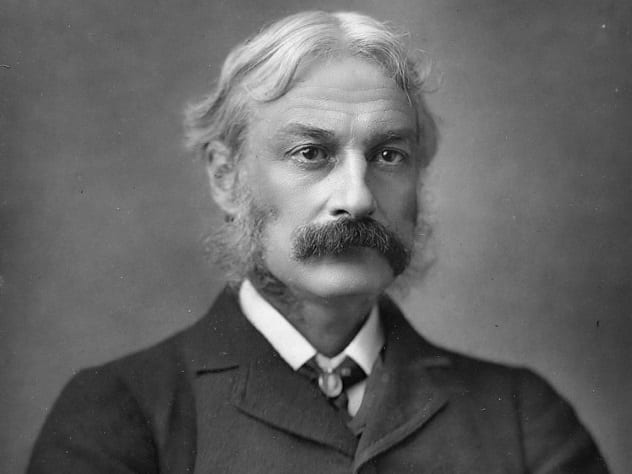

8 The Story Of Sigurd By Andrew Lang

The Red Fairy Book by Andrew Lang was one of Tolkien’s childhood favorites. One of the last stories in there was The Story of Sigurd. Humphrey Carpenter wrote a biography of the professor, in which he said that The Story of Sigurd was the best story Tolkien had ever read. Tolkien also once said that he was one of the children Lang was talking to with his stories. The Story of Sigurd comes from the Old Norse stories. Sigurd, the hero, wins fame and fortune by killing the dragon Fafnir and taking its treasure. The sword Sigurd uses was broken when his father died but is made again from the pieces. Tolkien used the same idea for Aragorn’s sword, which was broken when Elendil, Aragorn’s ancestor, fell to Sauron. The professor also thought that Fafnir was a better dragon than the one in Beowulf. In his letter to Naomi Mitchison, he told her that Smaug is based on Fafnir.[4]

7 The Book Of Dragons By Edith Nesbit

While we’re speaking of dragons, did you ever read The Book of Dragons by E. Nesbit? Nobody knows for sure if Tolkien read it, but Douglas A. Anderson believes that he probably did. The stories in The Book of Dragons were first published in The Strand in 1899, when the professor was seven. Tolkien told W.H. Auden in a letter that he once wrote a story when he was that age. All he could remember was that there was “a green great dragon,” which his mother said should have been “a great green dragon.” Maybe it was only coincidence, but in one of Nesbit’s stories, there were a lot of green dragons. One of them had gold wings and a “great green scaly side.” And the dragon in Farmer Giles of Ham is a lot like the one in another of the stories from The Book of Dragons, too![5] As the professor said in a letter to Roger Lancelyn Green, “One cannot exclude the possibility that buried childhood memories might suddenly rise to the surface long after.”

6 The Golden Key By George MacDonald

George MacDonald was another childhood favorite of Tolkien’s. In his book, Humphrey Carpenter says that the professor enjoyed the Curdie books. And in his essay “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien also mentions The Giant’s Heart, Lilith, and The Golden Key. In 1964, Pantheon Books asked Tolkien to write a preface to their new edition of The Golden Key. The professor wrote back saying that, “I am not as warm an admirer of George MacDonald as C.S. Lewis was; but I do think well of this story of his.”[6] And in “On Fairy Stories,” he called it “a story of power and beauty.” But Humphrey Carpenter says that after the professor reread The Golden Key, he found it “ill-written, incoherent, and bad, in spite of a few memorable passages.” Tolkien did start writing the preface in 1965, but instead, it became Smith of Wooton Major. The Curdie books inspired Tolkien’s orcs and goblins. The Golden Key includes a magical woman who is thousands of years old. The way MacDonald described this character is very similar to how Tolkien described Galadriel many years later: “She was tall and strong, with white arms and neck, and a delicate flush on her face [ . . . ] not only was she beautiful, but [ . . . ] her hair [ . . . ] hung loose far down and all over her back [ . . . ] it was white almost as snow. And although her face was so smooth, her eyes looked so wise that you could not have helped seeing she must be old.”

5 ‘Puss-Cat Mew’ By E.H. Knatchbull-Hugessen

In a letter to Roger Lancelyn Green, Tolkien remembers being “read to from ‘an old collection’—tattered and without cover or title-page.” One of the professor’s favorite stories was in that book: “Puss-cat Mew” by E.H. Knatchbull-Hugessen. Tolkien thought the “old collection” might have been compiled by Buwer Lytton. He was never able to find it again, but we think it was probably Stories for my Children, Knatchbull-Hugesson’s own collection. You can easily see the inspiration Tolkien drew from “Puss-cat Mew.” Most of the story takes place in “a large and gloomy forest” that sounds a lot like Mirkwood, Fangorn, and even the Old Forest. In it, there are ogres, dwarfs, and fairies. And in the original old collection, there was a picture of an ogre disguised as a tree. The professor at one point denied that he had been inspired by pictures but admitted to the opposite at others. But as noted in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment (edited by Michael D.C. Drout), this picture of the ogre as a tree calls to mind Tolkien’s Ents.[7]

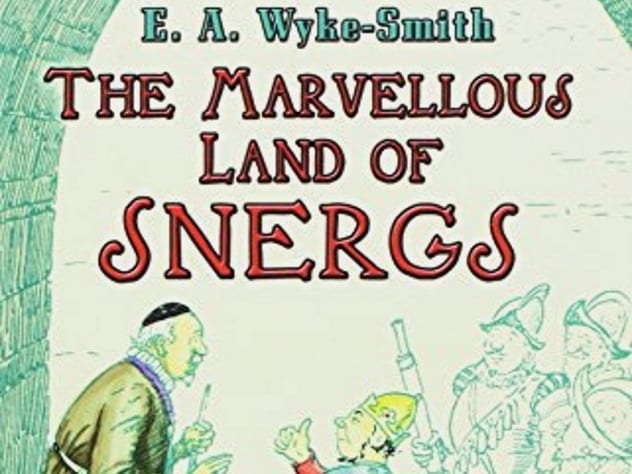

4 The Marvellous Land Of Snergs By E.A. Wyke-Smith

“I should like to record my own love and my children’s love of E.A. Wyke-Smith’s Marvellous Land of Snergs,” wrote Tolkien in his notes for “On Fairy Stories,” “at any rate of the Snerg-element of that tale, and of Gorbo the gem of dunderheads, jewel of a companion in an escapade.” Later, in his letter to W.H. Auden, the professor downplayed the influence of the stories when he said it “was probably an unconscious source-book for the Hobbits, not of anything else.” When Tolkien first began telling the story that would soon after become The Hobbit, it was to satisfy his children’s want for more stories about the Snergs. The Snergs are indeed very similar to Hobbits. Middle-earth and especially the Shire are also similar in many ways to the Land of the Snergs. One chapter, “Twisted Trees,” inspired the story of Bilbo and the dwarves in Mirkwood. In the earliest drafts of The Lord of the Rings, a Hobbit named Trotter helped Frodo from the Shire to Rivendell. Trotter was very much like Gorbo, the main Snerg character in The Marvellous Land of Snergs, who travels with two human children through the land.[8] Aragorn eventually replaced Trotter, but many of the similarities remained.

3 H. Rider Haggard

Tolkien was fond of H. Rider Haggard’s stories as a child. The professor supervised the revision of Roger Lancelyn Green’s thesis in 1943, and Green said that Tolkien ranked Haggard very high on his list of authors.[9] And in an interview with Henry Resnick, the professor also said that, “I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything.” But King Solomon’s Mines is easily the book that inspired Tolkien the most. The J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment points out that the inclusion of a map, details of the narration, and the adventure for ancient treasure all come out in The Hobbit. Even Gollum, the Glittering Caves of Helm’s Deep, and Gandalf’s difficulty choosing the right path in Moria seem to be inspired by scenes and characters in King Solomon’s Mines. Green lent Tolkien a book by Haggard, but the professor never mentions it. It doesn’t look like Tolkien ever revisited these stories as an adult. But that was probably a good thing—just look at what happened when he reread MacDonald’s The Golden Key!

2 The Night Land By William Hope Hodgson

C.S. Lewis once said that William Hope Hodgson’s novel The Night Land had an “unforgettable sombre splendor” in its images. He also complained that it was “disfigured by a sentimental and irrelevant” romanticism and flat writing in a poor attempt at a style older than itself. Douglas A. Anderson agrees with Lewis there but also points out that, “The Night Land is still a kind of masterpiece.” There’s very little evidence to suggest that Tolkien ever read any of Hodgson’s stories himself. But if you read The Night Land or even “The Baumoff Explosive,” you’ll find similarities all the same. Hodgson evokes the powers of darkness in a way that Tolkien does in the mines of Moria. This has caused Anderson (who wrote The Annotated Hobbit and compiled Tales Before Tolkien) to speculate that Tolkien probably did read The Night Land in the 1930s.[10] Perhaps his friend C.S. Lewis introduced him?

1 The Book Of Wonder By Lord Dunsany

Last but not least, we come to Lord Dunsany. Tolkien was interviewed by Charlotte and Denis Plimmer in 1967. They sent him their first draft of the article that was eventually published in the Daily Telegraph Magazine the next year. In it, they quoted the professor saying, “When you invent a language you more or less catch it out of the air. You say ‘boo-hoo’ and that means something.” Tolkien was not impressed. In his reply, he told them it seemed odd for him to have said anything of the sort, because it went completely against his own opinion. But he also said that if he gave any meaning to the phrase “boo-hoo,” it would be inspired by Lord Dunsany’s story “Chu-bu and Sheemish”: “If I used ‘boo-hoo’ at all it would be as the name of some ridiculous, fat, self-important character, mythological or human.” “Chu-bu and Sheemish” was published in 1912 as part of The Book of Wonder. Tolkien remembered the story fondly, but not the author’s style. The professor once said in a letter to his publishers that Dunsany failed to invent names coherently. But he did enjoy “The Hoard of the Gibbelins” enough to mimic it later in life when he wrote The Mewlips, which has a lot of similarities.[11]