However, for most people, Prohibition was a merry period marked with increases in drinking, gambling, and corruption. Above all, Prohibition encouraged high levels of creativity in attempts to get around the law at all levels of society.

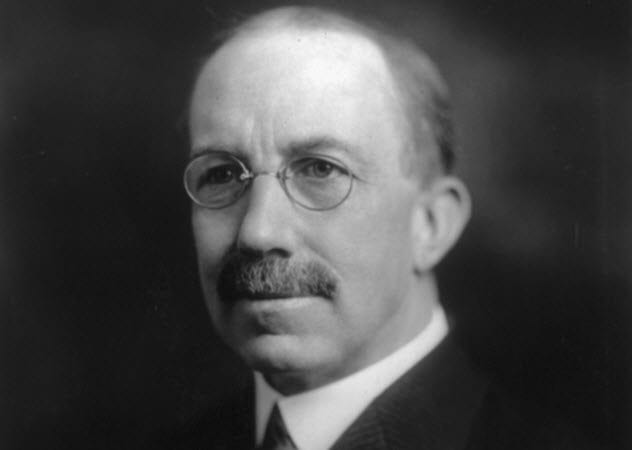

10 The ‘Dry Boss’ Who Pushed Prohibition Through

Wayne Wheeler was born in 1869 on a farm in eastern Ohio. One day, a drunken farmworker accidentally speared young Wheeler’s leg with a pitchfork, an incident that likely pushed him toward an almost evangelical antipathy for drinking. In 1894, Wheeler was offered a full-time position at the Anti-Saloon League where he quickly became admired for his pressure politics (aka “Wheelerism”). Unlike other temperance groups, the Anti-Saloon League didn’t stray from its main objective—the abolition of alcohol from American life. The league worked extensively through churches and supported or opposed government candidates depending only on their position regarding Prohibition. Due to his influence and power, Wheeler became known as the “dry boss.” Wheeler insisted on strict enforcement of Prohibition. He also opposed the use of soap and other harmless substances in denatured alcohol, instead opting for poisonous chemicals by arguing that “the person who drinks this industrial alcohol . . . is a deliberate suicide.”

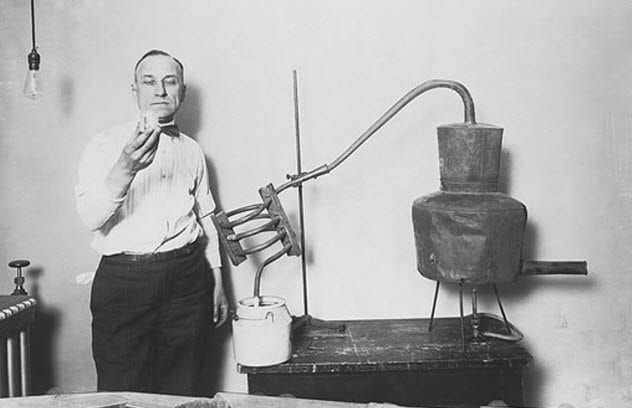

9 Prohibition Agents Were Paid Less Than Garbage Collectors

Contributing to Prohibition’s failure was the fact that most Prohibition agents were heavily underpaid. In fact, most Prohibition agents earned less than garbage collectors. The average national income was $3,143 in 1922 and rose to $3,227 in 1923. In comparison, the salary of Prohibition agents ranged from $1,200 to $2,500 for 98 percent of the Prohibition Bureau. In 1930, the entry-level salary of a Prohibition agent was $2,300, two-thirds of the national average. The Coast Guard earned even less. Men enlisted in the Coast Guard earned only $36 dollars per month, although that included accommodations and free uniforms. As one can imagine, underpaid agents often took bribes from bootleggers and sometimes even moonlighted as chauffeurs for their supposed targets. As a result, more than one-tenth of the agents were dismissed from the Prohibition Bureau.

8 ‘Cow Shoes’ Were Worn By Bootleggers To Cover Up Their Footsteps

To evade Prohibition agents, many bootleggers devised inventive ways to smuggle alcohol. One of the most unusual inventions was “cow shoes,” which were used to cover footprints in the woods where moonshine brewery sites were often hidden. The “cow shoe” was a strip of metal tacked with a wooden block that was carved to resemble the hoof of a cow. When strapped onto a human foot, the device left a trail resembling that of a cow. Supposedly, this confused and deterred agents tracking criminal operations. It was believed that the idea for “cow shoes” came from a Sherlock Holmes story in which the villain’s horse was shod with shoes that had imprints of a cow’s hoof.

7 Wine For ‘Sacramental Purposes’ Was On The Rise

The Volstead Act, which was passed in the year before Prohibition began, granted federal agents permission to investigate and prosecute anyone who violated Prohibition liquor laws. But wines used for sacramental purposes were exempt, which meant that a limited amount of wine could be made at home and in wineries. To acquire sacramental wine, some people went as far as to pose as priests and rabbis. In 1925, a study found that the demand for sacramental wine in the US increased by 3 million liters (800,000 gal) in a two-year period.

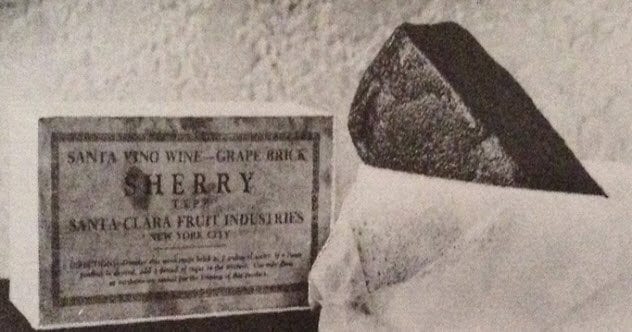

6 Wine Bricks Saved Many Vintners From Bankruptcy

No longer able to make wine on the premises, many vintners started producing “wine bricks,” which were bricks of concentrated grape juice. The target market was home brewers who could dissolve and use these wine bricks in the privacy of their own homes. Since grape juice was not illegal under Prohibition laws, wine bricks were truly an ingenious idea for vintners who did not have the heart to tear down their vineyards. The law could do nothing because the bricks came with warnings that they were for nonalcoholic consumption only. The packaging for wine bricks contained a note explaining how to dissolve the concentrate in 4 liters (1 gal) of water. Then the instructions helpfully “warned” the consumer not to leave the jug in a cool cupboard for 21 days or it would turn into wine. Wine brick makers also included the flavors (such as Burgundy or claret) that a person might encounter if they “accidentally” left the juice to ferment.

5 ‘Medical Beer’ Campaign Was Almost A Success

In 1921, a group of brewers, physicians, and avid alcohol consumers tried to convince the US Congress that beer—a substance that temperance leagues had associated with laziness, abandoned wives, and unemployment—was actually vital medicine. The so-called “beer emergency” was understood both by supporters and opponents to be a referendum on Prohibition itself. Advocates of beer pointed to its relaxing qualities and nutritional value. One writer even suggested that beer was so full of vitamins that it actually saved the “British race” from extinction during the plague years. Much to the annoyance of temperance league advocates, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer declared that the “beverage” clause in the 18th Amendment allowed doctors to prescribe beer at any time, under any circumstance, and in any quantity necessary. However, a few months after Palmer’s decision, Congress took up the beer emergency bill and banned beer completely. By the end of 1921, the bill had become law, much to the dismay of avid beer proponents.

4 Prohibition Administrators Often Drank Booze Themselves

Some Prohibition administrators did not adhere to the law themselves. For example, Colonel Ned Green, the administrator of San Francisco, was suspended from his duties in 1926 after Alf Oftedal, the assistant commissioner of Prohibition in charge of enforcement, came upon Green serving seized liquor at private parties. Later, Green amiably told reporters that he should have been suspended long ago. Following Green’s imbroglio, every administrator was asked to sign a pledge of abstinence. Prohibition officials also helped bootleggers to withdraw whiskey from bonded warehouses. In fact, two Prohibition administrators were accused of issuing withdrawal permits for $1 million of booze in just one day.

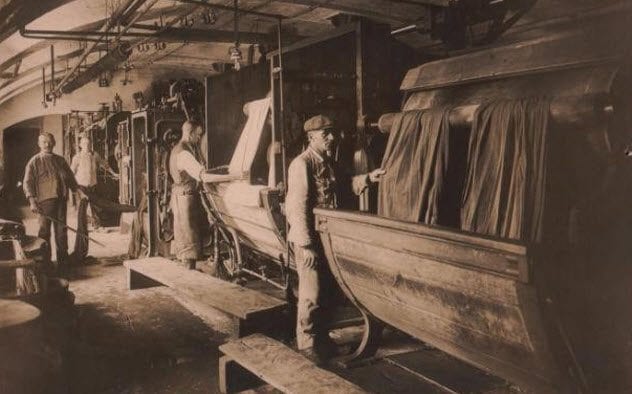

3 Breweries Found Innovative Ways To Keep Business Afloat

During World War I, the country was already moving toward a full alcohol ban. Breweries could only produce beer that did not exceed an alcohol content of 2.75 percent, better known as “near beer.” When Prohibition was put into effect, the number dropped to 0.5 percent. Not all brewers were content to stick to the production of “near beer.” Some, like F.M. Schaefer Brewing Company and Nuyens Liquers, decided to start making dyes. This turned out to be a successful enterprise thanks to the shortage of dye in the country at the time and the fact that brewers’ existing equipment could be converted into making dyes. Interestingly, some dye chemical plants also noticed the similarities between alcohol and dye production and started producing illegal booze. Other brewers—such as Schlitz, Miller, and Pabst—turned to producing malt extract, which was advertised as a cooking product. In reality, however, people bought it for the purpose of making their own beer or “home brew.” Still others, such as Anheuser-Busch and Yuengling, turned their attention to ice cream.

2 Children’s Menus Originated During Prohibition

Before Prohibition, children rarely ate out. In fact, a child had to be relatively well-off and a guest at a hotel to dine in public. Restaurants not attached to hotels rarely served children because they got in the way of booze-induced adult fun. When Prohibition went into effect, the owners of restaurants and other hospitality establishments suddenly changed their minds, realizing that children could help to offset the lost liquor revenue. In 1921, the Waldorf Astoria in New York became the first establishment to produce a children’s menu. Other restaurants soon followed. But these new menus meant the establishment of a new limitation: At restaurants, children could no longer eat what their parents ate.

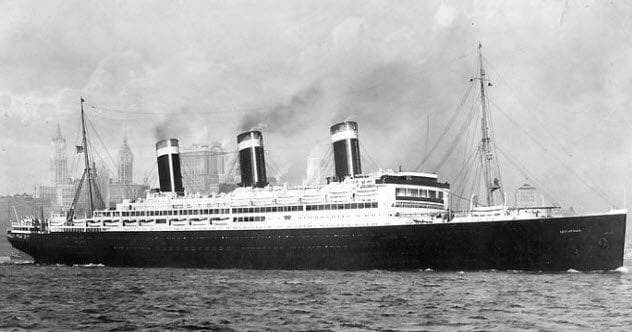

1 ‘Cruises To Nowhere’ Were Popular

During Prohibition, you could legally drink alcohol outside the 5-kilometer (3 mi) territorial limit of the United States. As a result, “booze cruises” or “cruises to nowhere” became popular. As the name suggests, “cruises to nowhere” were short cruises with no particular destination during which guests could indulge in alcohol to their hearts’ content. Famous liners like the Berengaria and Aquitania of Cunard, the Majestic of White Star, and the Leviathan of United States Lines all offered these trips. Some were simply weekend cruises into the Atlantic, while others also made stops in Nova Scotia or Bermuda. Short sailing trips to the Bahamas and Havana also became popular. There, clubs and other drinking establishments sprang up to cater to thirsty Americans. Laura is a student from Ireland in love with books, writing, coffee, and cats.