10 Raza Unida Party

In the 1970s, the Raza Unida Party (RUP) formed in Texas through a number of spontaneous grassroots political organizations. While nobody knows exactly when and where the party started, RUP filed as a political party in several Texas counties in January 1970. RUP politicians wanted autonomy and nationalism for the Chicano population of Mexican Americans. Anybody could join the party, regardless of ethnicity, but everyone was committed to the party goals of bilingual education, equal pay, more oversight over police forces, and increased self-determination for the Chicano population. Over time, RUP goals drifted more toward revolutionary ideals. With the influx of illegal immigrants, RUP representatives favored loose control and began to talk about communal living, ideas that were more in line with the far left of the 1960s. Although many Texans were not happy about RUP and opposed its ideals, many RUP candidates ran for political office during the 1972 state elections. Despite the initial excitement of RUP representation, no RUP candidates won their elections. Undeterred, RUP ran in gubernatorial races in 1974 and 1978. However, the party was hurt by laws that required filing fees and by voter apathy toward RUP. The excitement of 1972 died down quickly, and the 1978 race was RUP’s last major political move. On a national scale, RUP remained relatively unknown, but its influence was big on younger Chicano activists.

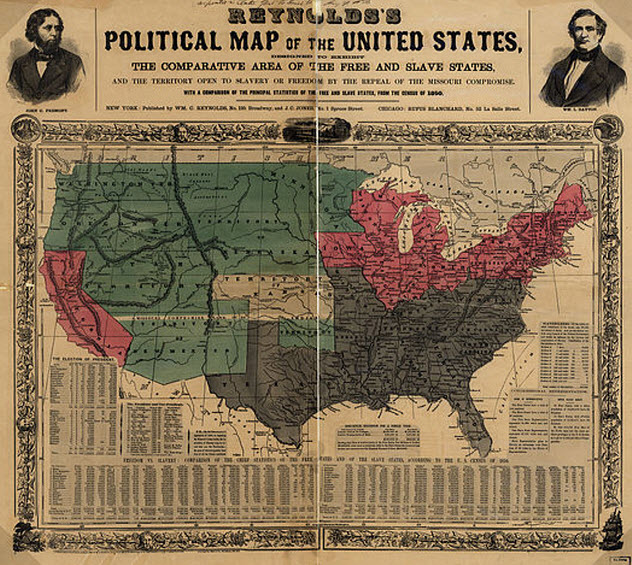

9 Anti-Nebraska Party

In 1854, the US created the new territories of Kansas and Nebraska, expanding slavery into these areas in a shocking reversal of earlier decisions. Instantly, this energized the country into taking sides in a new antislavery debate. With the Whig Party rapidly disintegrating, it was obvious that the Southern-influenced Democrats held nearly unlimited control over the US government, which allowed slavery to expand into new territories. At first, the anti-Nebraska activists formed a loose coalition that united over disagreement with the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Eventually, politicians—including a young Abraham Lincoln—realized that they would need to organize into a political party to have any say on the national level. To do this, they began to hold debates and publish tracts about the need to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the Whig Party, the Anti-Nebraska Party embarked on a campaign to bring as many Whigs to their side as possible. They also made appeals to Northern Democrats who opposed slavery but were uncomfortable with the federal government. With these groups coalescing, the Anti-Nebraska Party combined with the Free Soil Party, another third party whose only platform was to stop the spread of slavery. Together, they became the chief opponents of the Democrats on a local level. Once they got a foothold, they renamed themselves the Republican Party and completely pushed the Whigs out of the national scene.

8 Liberal Party (Utah)

When Mormon settlers founded Utah in the mid-1800s, they set up a governmental system focused on church authority. In the early settlements, religion and politics were intertwined, and there were few political contests about the laws and leaders of the territory. That began to change when William Godbe left the church in the 1860s. With Godbe and his followers establishing political opposition to the government of Brigham Young, the territory faced political rivalry for the first time. Initially, this group was known as the Godbeites, but they eventually renamed themselves the Liberal Party. Their platforms were stridently anti-Mormon but mostly from a political and economic angle. Liberal Party members opposed the hegemony of the Brighamite government and wanted Utah to become more integrated with the American mainstream. By the time that the Liberal Party officially organized, Utah politics had broken down along religious lines. Mormons supported the pro-Mormon People’s Party; everyone else sided with the Liberal Party. Liberal politicians always did poorly in state elections because Mormons far outnumbered the non-Mormons in Utah. Notwithstanding their lack of electoral success, the Liberals were key to increasing the separation between Mormon leadership and territory politics. Still, party membership declined rapidly as Utah approached statehood. When the US added Utah as a state, the Liberal Party and the People’s Party survived for only a short while. Mormon leaders encouraged members of the People’s Party to join national parties to get Mormons more involved in national politics. Before they could make an impact on the national scene, the Liberals followed suit and were absorbed into the national Democratic and Republican Parties.

7 Home Rule Party

The Home Rule Party of Hawaii, another local third party, organized with the goal of representing Hawaiian concerns more effectively on a national scale. In the early 1900s, the Hawaiian people did not believe that the national Democratic and Republican Parties represented them. Robert William Wilcox, a Hawaiian politician, led the organization of the Home Rule Party to offer an alternative for Hawaiian voters. Wilcox led the Home Rule Party in a strict nationalistic platform. During their first election, the party won a plurality in the territorial government. Soon, the US decided to give Hawaii one nonvoting representative in the US House of Representatives. In 1901, Wilcox won election as the delegate and went to Washington, DC, to represent the island chain. In the House of Representatives, Wilcox had little influence on his fellow politicians. As a third-party delegate, his role in crafting legislation was limited, and his difficulty with speaking English complicated his problems. His lack of results in Washington made the Hawaiian people skeptical about the Home Rule Party, causing the party to suffer crushing electoral defeats in the 1902 elections. In 1903, Wilcox died of hemorrhages. By 1912, the Home Rule Party had fallen apart.

6 Christian Freedom Party

The Christian Freedom Party (CFP) was the brainchild of politician Thomas Harens, who became dissatisfied with the traditional political parties in 2004. He felt that progressive, moderate Christians were not properly represented in the US. According to Harens, the Republicans had moved toward a version of Christianity that was too extreme for his taste, and the Democrats spent too much time vilifying good Christians. A key aspect of the CFP was contained in Harens’s statements that belief in God should transcend politics and that good Christians should support godly policies regardless of their political leanings. With that in mind, the CFP held many mismatched positions. They believed in universal health care but wanted to ban abortions. They favored small government but still believed in strict environmental protection and the government’s participation in a cure for the AIDS epidemic. During the 2004 election, some political commentators felt that Harens was attempting to pull votes away from George Bush to ensure a John Kerry victory. Unfortunately, Harens barely made a dent with his party. However, he felt that any votes for the CFP would give people a chance to talk about his policies, which became his measure of success. The CFP fell apart after Harens’s electoral loss.

5 Youth International Party

Antigovernment counterculture movements were the face of the radical left during the 1960s. Fueled by societal upheavals and antiwar sentiment, counterculture groups attempted to bring about important changes in the world around them. One of the strongest groups was the Youth International Party (aka “Yippies”), a far-left organization of young political demonstrators that became an American third party. The Yippies held the hallmark beliefs of 1960s counterculture. They advocated looser restrictions on drugs, strict antiwar policies, and sexual liberation. Yippies were unique in the way they broadcast their messages. They participated in street art, counterculture performances, and mischievous pranks. Their pranks and theatrics earned them the nickname “Groucho Marxists.” Although the Yippies did not run real political candidates for office, their theatrics influenced the US politicians and citizens of the time. Their biggest moment came during the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention when Yippies spread rumors that they had laced the Chicago water system with LSD. The Yippies also nominated a pig named Pigasus as their presidential candidate during the convention. Following a riot, the police arrested key Yippie leaders. Although they were put on trial, the Yippies didn’t stop their antics. The group died out in the 1970s as the counterculture movement lost steam. As a result, Pigasus never got to sit in the White House.

4 Proletarian Party Of America

The US has had a variety of socialist and communist political parties during its history. The Proletarian Party of America (PPA) emerged from the better-known Communist Party USA. Specifically, the PPA formed from a smaller socialist party in Detroit after World War I and quickly became influential in American left-wing politics. PPA leaders attempted to ally with the Communist Party, but the two parties disagreed on key issues, especially the method by which a communist revolution should occur in America. While the Communist Party followed a more revolutionary concept of Marxism, the PPA focused on educating the masses. The PPA believed that communism would only take hold in the US if workers were sufficiently educated about the tenets of communism, after which they would decide for themselves to undertake a communist revolution. From the start, the PPA suffered internal schisms and disagreements. Most party members stubbornly refused to align with other American communist parties. This distanced the PPA from the mainstream of American communism. Even so, the PPA survived into the 1970s. But they eventually fell apart when the head of the party died with no clear successor.

3 New Party

Now defunct, the New Party was once a moderately successful political party that ran on the platform of reinventing the electoral process. New Party politicians believed that the US voting system heavily favored the two major parties and did not give third parties a reasonable chance to have their candidates win elective office. To combat this, New Party leaders proposed that the US engage in electoral fusion, in which a candidate could run on the ticket of more than one party. Total votes across parties would then be counted for that politician. This was expected to give third parties more representation in the US government and increase voter participation. The New Party strategy was to get as many candidates into the public spotlight as possible. In addition to electoral fusion, the party endorsed mainstream progressive politics and often placed Democratic candidates on their ballots. The New Party also introduced the idea of candidate contracts. If a candidate wished to get a New Party endorsement, they would sign a legally binding contract, agreeing to uphold the values and ideas that they espoused when they received the endorsement. Throughout the mid-1990s, the New Party was mildly successful. But they did not have enough influence to make a huge difference on the political scene and died out before the turn of the 21st century. Oddly, New Party ideals may still be influential today. During Barack Obama’s first run for state senate, he signed a New Party voter contract and may have even joined the party briefly to give himself an edge in the election.

2 Anti-Masonic Party

Most people have heard of the Freemasons but do not give them much thought. Besides a few conspiracy theorists, most people don’t have much of an opinion about the Freemasons. However, during the 1820s, that was not the case in the US. Most Americans believed that the Freemasons were a secret, insidious society that would undermine the principles of the US constitution. In that atmosphere, politicians created the first American third party, the single-platform Anti-Masonic Party. The Anti-Masons began when William Morgan died under mysterious circumstances after leaving the Freemasons and threatening to write a book exposing their secrets. Outraged by the incident, citizens of upstate New York actively worked to keep any Freemasons from taking public office. Eventually, this became a full-blown political platform, with Anti-Mason candidates running for and winning local elections. Politicians published their own newspapers, and Anti-Mason fervor soon swept the country. With interest in their party increasing, the Anti-Masons held a national convention in 1831 to decide who should run for president on their ticket. Anti-Masons continued to run for the White House until their party fell apart in 1840. Most Anti-Masons merged into the new Whig Party to challenge the Democrats, spelling the end of the Anti-Masons as an independent party. Although short-lived, the party was influential in American politics. They were the first “third party” in American history, the first party to hold a national convention to choose a presidential candidate, and the first party to issue platform statements.

1 American Vegetarian Party

Another third party with a single platform was the American Vegetarian Party (AVP). Formed in 1947, the AVP ran their first presidential candidate in 1948 and continued to do so until the party died out. Throughout its history, the AVP championed progressive ideas of the time, including equal rights. Of course, the AVP focused on ending meat consumption in the US but also favored strict control of alcohol and tobacco. Party officials were concerned about the overuse of medicine, too. In 1948, the AVP ran 85-year-old Dr. John Maxwell for president, but they hardly siphoned any votes from the main Democratic and Republican Party candidates. For most of the 1950s and ’60s, candidates ran on the Vegetarian ticket in US elections, but a lack of support eventually killed the party. Although they didn’t have much political influence on the national scene, the AVP normalized vegetarianism in the US and educated people about the meat industry. Recently, some people have attempted to revitalize the AVP as a political party, but their efforts have been unsuccessful so far. Zachery Brasier is a physics student who likes to write on the side.