10 Edward Palmer And The Boston Stocks

In colonial America, rapidly growing villages were required by law to have facilities to control the most unruly of their citizens. If not, the villagers could be subject to a fine. In the early days of Boston, town officials imported their implements of restraint from England, bringing over iron bilboes, device which were little more than iron bars with shackles affixed to them. A bilbo held the guilty party by the feet, resulting in the common sentence of public display and humiliation. But bilboes were expensive. Iron was a hot commodity at the time, and colonial bookkeepers started weighing their options. As Boston grew, they knew they would need to import more bilboes. But even though iron was pricey, wood was cheap. And it was everywhere. The authorities decided to build a set of stocks so they could phase out bilboes. In 1636, they hired a carpenter named Edward Palmer to build the stocks, which seemed like a good idea until he handed the young city a bill they considered to be outrageously high. The magistrates wasted no time in charging Palmer with extortion. He was found guilty, fined £5, and sentenced to spend an hour in the stocks he’d just finished building.

9 Captain Thomas Kemble’s Lewd Kiss

Thomas Kemble was a major player in the shipping industry, a well-off merchant who imported household goods and necessities into Massachusetts. He also exported lumber to England from his New England lumber mills. Kemble was held in such high regard that he was sent a group of Scottish rebels, with orders to deal with them as he saw fit, most likely selling them into indentured servitude. In the 1650s, Kemble’s work took him away from home for long periods of time. When he returned from a three-year business venture one Sunday in 1656, his wife met him at the door to their home. Unfortunately, he kissed her, which was ruled “lewd and unseemly behavior” under Puritan law. As it was a Sunday, his crime was considered to be doubly bad. Kemble was sentenced to two hours in the public stocks for indecent actions. When it came to displays of affection, single men faced almost as many rules and restrictions as married ones. In some communities, a single man had to receive special permission from the town to live there. If the man settled down without getting the necessary approvals, he had to pay a weekly fine.

8 Captain John Underhill’s Banishment

After his family participated in a failed plot to overthrow the queen of England, John Underhill and his wife became part of a group of Puritan exiles living in the Netherlands. In the 1620s, he and his wife immigrated to the new colonies in America. There, Underhill became an upstanding member of his community. He was hired to train the Massachusetts Bay Colony militia, and he held powerful offices. However, Underhill made the mistake of supporting the teachings and beliefs of a reverend whom mainstream Puritans had decreed to be a heretic. When the reverend was thrown out of the colony, Underhill was removed from his positions and accused of adultery. Whether or not it was true, Underhill was excommunicated from the church as well as the community. In 1640, he returned in an attempt to beg his way back into acceptance. The governor escorted him into the church. After the pastor’s lecture, Underhill confessed his sins in front of the people who had been his neighbors. His list of sins included adultery, hypocrisy, pride, contempt, persecution of God’s faithful, and a fall into the grip of Satan. He told of how God had sent him all kinds of terrors and visions until he couldn’t sleep or function, driven to despair lamenting what he’d done. He begged, he cried, and he sighed. Finally, he was accepted back into the church and the community. But his adultery wasn’t forgiven so easily. For that, he also had to admit that it had taken him six months to persuade the woman to give in to him, and then he had to beg the forgiveness of her husband. According to the records, the husband freely forgave Underhill.

7 Dishonoring The Sabbath

Historical records are filled with the names and misdeeds of people found guilty of dishonoring the Sabbath in colonial America. Some individuals were arrested, fined, or both for violations like picking apples or peas, catching eels, or even putting a bit of old hat in a shoe. Supposedly, the latter protected the foot during hard labor. But if the piece of hat was placed in the shoe on the Sabbath, it clearly showed the intent to work. One couple was put on trial for sitting under an apple tree on the Lord’s Day. Other offenses included washing and hanging clothes, driving a yoke of oxen, and racking hay. In 1658, a man named James Watt was publicly humiliated for writing a business-related note on the Sabbath. Even though he’d waited until evening to do it, the court believed that he hadn’t waited long enough. In Vermont, actions like riding, dancing, jumping, or “hallooing” on the Sabbath meant a fine and a whipping but not more than 10 blows. New Haven was even stricter, with laws that punished profanity on the Lord’s Day with corporal punishment, imprisonment, or death. Even people with the best intentions ran afoul of these extreme laws. A Maine man was fined for “unseemly walking.” Only after he produced several witnesses to testify that he’d been running to save a man from drowning was his fine returned to him. In an even stranger case, a Norwich man named Samuel Sabin turned himself in to the courts after he visited some relatives on a Sabbath night because he was so consumed with guilt that he wanted to make sure he wasn’t violating any laws.

6 William And Dorcas Hoar

In his hometown of Beverly, Massachusetts, William Hoar, 33, drew the attention of the authorities in 1662 for inviting some townsfolk to his house to celebrate the Christmas season with a few drinks. That’s all we know about the incident, but the Hoar family’s rebellion against the leaders in their community was legendary. The Hoars disliked their local minister so much that they often broke into his house when he was gone and helped themselves to his belongings. In 1678, William’s wife, Dorcas, was arrested for leading a burglary ring that included her own daughters as thieves in training. A search of their house uncovered some stolen goods, but the records are unclear on what happened in that case. By 1680, William was in charge of caring for the town’s meetinghouse, while Dorcas was gradually becoming more witchlike. Documents from 1689 describe her as being dressed like a witch, and by the winter of 1692, William had mysteriously died. The investigation into his death was canceled because of Dorcas’s impassioned protest. But in May of that year, Dorcas became a defendant in the Salem witch trials. For years, Dorcas had proudly proclaimed herself to be a fortune-teller and palm reader. She also did everything she could to imply that she was a witch. As a result, William’s mysterious death was used as evidence against her. She was sentenced to hang that September—not for the crime of killing her husband but for witchcraft.

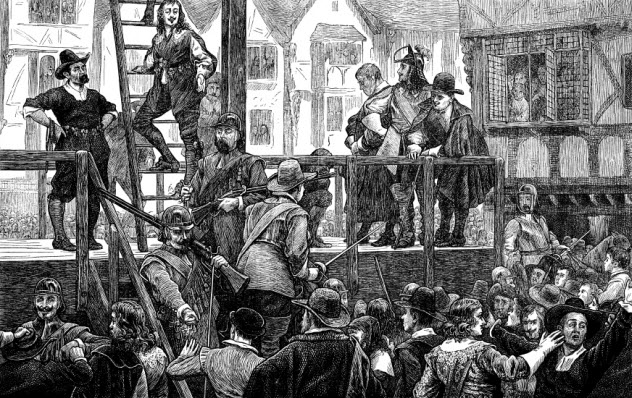

5 The Puritans vs. Mary Dyer And The Quakers

Many of those who moved to the colonies for religious freedom wanted it only for themselves. When the Quakers started showing up, they were rejected by earlier settlers, especially in Boston. Any ship bringing Quakers into the port was fined. In at least one case, the captain had to return the Quakers to England where he’d picked them up. In addition, the Quakers were strip-searched, jailed, starved, and relieved of all their worldly possessions. Between 1656 and 1661, around 40 Quakers made a stand against the persecution of the Puritans. They were a nonviolent group, but that didn’t make them any less annoying. They set up in public places, gave speeches, and returned every time they were arrested and kicked out of town. In 1633, Mary Dyer arrived in Massachusetts with her husband. She became a Quaker on a return trip to England and realized it was her life’s mission to spread the Quaker word. When she came back to the colonies to rejoin her family, she was jailed in Massachusetts with two other Quakers. Later, she was freed and left for Rhode Island, her family’s new home. But Dyer returned to Massachusetts to visit her fellow Quakers as they sat in Puritan jails. In 1659, she was also jailed and sentenced to hang with two friends. Those two met their end on the gallows, but Dyer was pardoned at the last moment. She promptly refused to get off the gallows until the laws governing the treatment of Quakers were changed. Needless to say, they weren’t changed, and she was carried off. She left through the winter months but returned in the spring. She was arrested and sentenced again. However, she did have one last chance. The governor promised to free her if she renounced her beliefs, but she refused. Dyer was hanged on Boston Commons and buried in an unmarked grave. When word of her death got back to King Charles II, he banned Quaker executions.

4 The Obligation To Arms

In early America, it was generally the law that all men older than 16 bear arms. In some areas, exceptions were made for certain ethnic groups or people whose loyalty and trustworthiness was in doubt. But for the most part, men were expected to carry a gun everywhere. In 1619, Virginia enacted a statute that ordered everyone to come to church on the Sabbath with their guns. If they didn’t, they would be fined three shillings. In 1643, Connecticut law stated that everyone was expected to come to church with “a musket, pystoll or some peece, with powder and shott.” The Massachusetts Bay Colony had similar laws in place, designed to help protect the town’s population from the constant threat of attacks. These laws also applied to town and public meetings. In Rhode Island, anyone who showed up without a gun and ammunition would be fined five shillings. Most of the earliest laws specified that each weapon needed to have at least one charge, but by 1657, a Plymouth law raised that to six charges. In the 1630s, there were also laws requiring people who traveled through particular areas to be armed. Rhode Island law stated that anyone traveling more than 3 kilometers (2 mi) out of town had to carry a gun or pay a five-shilling fine. No one was allowed to travel the road between Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony alone or unarmed. Maryland’s vaguely worded law stated that no one was allowed “any considerable distance from home” without a weapon prepped to fire at least once.

3 Dorothy Talby’s Orders From God

In December 1638, Dorothy Talby was one of the first women to die by court order in the colonies. Originally, Talby was a godly woman, but by the early 1600s, neighbors began reporting a certain amount of mental instability in her. In 1637, she was chained to a post as punishment for abusive acts toward her husband. When her abusive behavior continued, she was excommunicated and then whipped. In December 1636, the Talbys baptized a daughter named Difficulty. With Difficulty’s arrival, Dorothy Talby sank further into a melancholy depression. According to her, she was visited by the voice of God who commanded her to kill her child. Doing so would save Difficulty from a future of misery, so Talby broke her daughter’s neck. She never denied her actions but insisted that it was done under the guidance of God. When she refused to issue a plea in court, she was told that she would be pressed to death. She asked to be beheaded instead. However, the sentence was based on England’s law, and two days after she was convicted, she was hanged in Boston. She didn’t go quietly, though. She fought the hangmen the entire way. After her death, Talby was written about in different regards. Nathaniel Hawthorne considered her to be a wrongly persecuted wife who was originally chained to a post in the hot sun for standing up to her husband. Much later, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that Talby had been suffering from a mental illness that should have been addressed long before the death of Difficulty.

2 Mary Latham And James Britton

In 1640s Massachusetts, Mary Latham was 18 when she was rejected by a man with whom she’d fallen in love. Following through on a promise to marry the next man who approached her, she quickly married a man three times her age. Shortly afterward, she met James Britton, who was reportedly charming but had a reputation as a womanizer. During a gathering with friends, Mary and James went off to have sex in the woods, where they were observed by many of the partygoers. When the gossip got back to Weymouth authorities, they arrested both parties, who admitted to the affair. The case was escalated to the Boston courts, but there was only one witness who testified to seeing the actual act of adultery in the woods. That made sentencing difficult. With only one witness, there might not be enough evidence to justify the death penalty. However, when the confessions of Mary and James were taken into account, the sentence was handed down based on Leviticus 20:10, which specified that adultery was a capital offense against God. On March 21, 1644, Mary Latham and James Britton each made speeches to the assembled crowd, warning them of the dangers of sexual indiscretions. Then they were hanged. However, their cases are unusual. Even though the death sentence could be handed out for adultery, it rarely was. More often, the hanging was symbolic, with a woman sentenced to stand on the gallows with a noose around her neck. But Mary Latham had confessed to a series of extramarital affairs, which hardened the judges’ resolve to put her to death.

1 Thomas Morton, Merrymount, And The Maypole

In 1624, Thomas Morton left England for the colonies. As a senior partner in a trading company backed by the Crown, he had the means to do well in the New World, where he originally settled in Quincy, Massachusetts. He and his partner, Captain Wollaston, eventually parted ways when Morton learned that Wollaston was selling their indentured servants as slaves to tobacco plantations in the South. As Morton didn’t like the Puritan way of life, he took the remaining servants, organized a rebellion, and set off to found his own settlement with their help. Morton called the settlement “Merrymount” and himself a “host.” It was a fun place, but they committed an especially serious sin in the eyes of the Puritans: The inhabitants of Merrymount mixed with the nearby Algonquin tribe. The trade partnership with the Algonquins meant that the people at Merrymount were able to live much more comfortably than the Puritans, who were largely starving at the time. Partially to attract some Algonquin women to their community, Morton decided to throw a big party at Merrymount, with lots of alcohol, music, dancing, and a maypole. This was the last straw for the Puritans. Led by Myles Standish, a Puritan detachment stormed the party and arrested Morton. No one resisted because everyone was drunk. Morton, who still had friends in high places in England, was dumped on the Isles of Shoals until he was rescued by a ship on its way to England. By the time he returned to Merrymount, a plague had all but wiped out his Algonquin friends, and his own people had fled. When the Puritans got wind of his return, they arrested him again, sent him packing, and burned down what was left of Merrymount. Back in England, Morton sought revenge against the Puritans, eventually getting the charter for their Massachusetts Bay Colony revoked. Unfortunately, the English Civil War was starting, and the Crown couldn’t afford to send troops to America to carry out the order. Morton returned to Plymouth by himself and was arrested as an agitator. He was granted clemency and released from prison, spending the rest of his life in Maine. He died in 1647. The former Merrymount settlement became Wollaston, home of Anne Hutchinson, another thorn in the Puritans’ side, and later the birthplace of John Hancock. Read More: Twitter