10 The Black Codes

In the years after the Civil War, the Freedman’s Bureau provided some much-needed support for slaves who had been emancipated but not given the resources that they needed. Not everyone agreed with the idea, of course, and individual states instituted the so-called “Black Codes” in order to continue to restrict the freedom of those that had just been granted it. The Black Codes were so restrictive that they were practically slavery. Freed slaves weren’t allowed to vote, travel freely, or even marry. Slavery was turned into “labor contracts” that had so-called “servants,” who worked for “masters” and were subject to all the regular whippings and confinement that they had supposedly just gotten freedom from. The codes also forbade the possession of firearms. Mississippi’s Black Code read, “No freedman, free Negro, or mulatto not in the military service of the United States government . . . shall keep or carry firearms of any kind, or any ammunition, dirk, or Bowie knife.” The punishment for getting caught with any of those was a fine and arrest. The same punishment was doled out to any white citizen who provided the restricted parties with guns or ammunition. The same section also forbade things like organizing riots, making speeches designed to cause an uproar, or providing the services of a minister without being licensed by a church. The codes echoed earlier sentiments that prohibited slaves from owning so much as a staff or club. Those laws, written in Virginia as early as 1705, were a part of the slave code. The continuation of the slave codes as Black Codes was about as popular as you’d imagine. At the same time that women were writing of having no way to defend themselves as they were attacked, beaten, and raped by the ex-Confederate soldiers who lived near them, Ida B. Wells wrote, “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for the protection which the law refuses to give.”

9 The Miller Act

In 1927, Washington State politician John Miller took aim at a practice that even today seems a little strange—selling and sending guns through the mail. His biggest issue was with small firearms like pistols, which he claimed were the weapon of choice for the criminal element. He also said that the practice made it much easier for minors to get their hands on a gun. The idea that there needed to be controls put in place was started largely because of the violence that was going on in connection with Prohibition and bootlegging. Gangsters were getting bigger and better guns (and more of them), and sales of pistols were skyrocketing. He drafted a bill that’s also known as the Mailing of Firearms Act, which is still in effect. Signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge, it bans the mailing of any small firearm that could be concealed on a person, and it received huge support from the National Association of Post Office Clerks. The debate on whether or not the bill was going to do any good had been raging for several years by the time it was finally signed into law. Some government representatives went on record as saying that it was going to do nothing to keep guns out of the hands of the criminal element, and that it wasn’t going to decrease gun crime in the least. The Southern and Western states had plenty to say when it came to opposing the bill. When it was signed into law, they turned out to be somewhat right. In the end, the law only prohibited the mailing of guns through federal channels, and people simply started sending their small firearms through privately owned carriers.

8 The Gunpowder Incident

Even before the US was officially the US, guns—and gunpowder—were the stuff of legendary disputes. On April 21, 1775, British troops were ordered to the Williamsburg magazine (pictured above) to seize barrels of gunpowder. Between 3:00 AM and 4:00 AM, they successfully requisitioned 15 barrels with only one loss reported—a bayonet scabbard. When the Williamsburg residents woke up the next morning, they were, of course, outraged. The city demanded an explanation, and as word of the troops’ movement spread, so did the gathering of Virginia militias. With Patrick Henry at the head of the movement, thousands of men started to march toward Williamsburg with every intention of either getting their gunpowder back or making the British pay for what they took. Tensions had already been running high, and the theft came on the heels of Henry’s famous “Liberty or Death” speech, which had already made it clear how things were going to be going under British rule. Peyton Randolph, president of the Continental Congress and mayor of Williamsburg, went straight to the source of the orders in an attempt to sort things out before the militia got into the city, and things went sideways. Lord Dunmore, the governor of Virginia, claimed that the move had been made after he had become aware of plans being made for a slave-led uprising. Not thinking that the gunpowder was secure enough where it was, they simply moved it to a more secure location—a British 20-gun man-of-war. And they had to do it in the middle of the night, he claimed, to prevent chaos and alarm from sweeping through the city. Randolph accepted the explanation and convinced Henry and his militia to stand down. Dunmore paid for the gunpowder he’d taken, but the truth of his explanation was highly suspect. While there had been numerous reports of unrest growing among Williamsburg slaves, others argued that taking gunpowder out of a city’s magazine in the dead of night had absolutely nothing to do with putting down a slave uprising.

7 The First Laws Against Concealed Carry

Whether or not it should be legal to carry a concealed weapon has long been a hot-button topic—since at least the early 1800s. The first legislation that made it illegal to carry a concealed pistol came from Kentucky in 1813. Indiana, Georgia, and Arkansas were close to follow their example, but it wasn’t for another 100 years until the idea would become common. It wasn’t long before the law was challenged in court as unconstitutional. In 1822, Bliss v. Commonwealth took a look at a case that wasn’t even about firearms but rather a sword cane. Bliss had been found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon and was fined, while his attorneys argued that the stipulation went against the state’s constitution, which allowed for an individual to “bear arms in defence of themselves and the state.” Since the wording on that was pretty vague, and another part of the constitution ruled that laws in opposition to any part of said constitution were void, it was argued that he had every right to carry the sword cane to defend himself. The ruling was that the indictment for carrying a concealed weapon and the law it was based on was in complete opposition to the guidelines laid out in the state constitution. The matter was rectified later, with a concealed weapons clause making it into Kentucky’s new Constitution of 1850.

6 Nazi Gun Control Theory

One of the go-to rallying cries for pro-gun, anti–gun control enthusiasts is the idea that gun control in Nazi Germany led to the Holocaust and made German citizens helpless, unwilling participants in the Third Reich’s evil deeds. There’s even an often-repeated quote that goes along with that rhetoric: “This year will go down in history! For the first time, a civilized nation has full gun registration! Our streets will be safer, our police more efficient, and the world will follow our lead in the future!” Sounds terrifying, right? The idea of Nazi-era gun control has even been mentioned in official, legislative literature . . . so how true is it? According to a paper written by the Law School of The University of Chicago, it’s shady at best. When they investigated just when Hitler might have uttered the above-mentioned quote, they found nothing at all. There were no witnesses, no credible dates, and no credibility whatsoever. The date usually given in reference to the quote is 1935, but gun control was already in effect in Germany. It had been for some time, and it had been started in part to control the out-of-hand street violence that was already associated with the Nazis. Most of the early gun control legislation itself didn’t come from the Nazis, either, it came from the Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919. Decades later, the idea of Nazi gun control is one that’s spewed all over the US as a reason why gun control shouldn’t be a thing. In October 2015, Ben Carson repeated the story, much to the ire of groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, which both said that representing gun control in such a way was inaccurate and insulting to victims of the Holocaust. In a series of laws eerily like the Black Codes, there were a whole host of restrictions placed on Jews living in 1930s Germany. Among those restrictions was a ban called The Regulations Against Jews’ Possessions of Weapons, which covered not only firearms but cutting weapons as well—a law that was instituted in 1938, several years into the Nazi reign.

5 Making Gun Ownership Mandatory

At a time when many places—especially those outside the US—are suggesting that fewer people have guns, there are a few towns in Georgia that went in the completely opposite direction. In 2013, Nelson, Georgia, council members unanimously voted to pass an ordinance that made it mandatory for every person designated as a head of household to own a gun and ammunition, in order to be able to protect that household and in case of a city emergency. The ordinance was largely symbolic, with exceptions allowed for people with mental or physical disabilities or for those that simply didn’t want to own a gun. There were no penalties for not having a gun. While the council members said that the ordinance was simply meant to make a strong statement toward a government that was considering gun control, some citizens felt that the idea of an ordinance that wasn’t meant to be enforced was a dangerous precedent to set. It wasn’t long before the motion was overturned, when one of those citizens sued on the basis of the idea that it was, ironically, an unconstitutional demand to make. That’s not exactly what happened when another Georgia town, Kennesaw, which made gun ownership mandatory in 1982. According to Kennesaw’s police department, crime not only went down, but stayed down. They also report that it’s been hugely popular, with the town growing from about 5,000 people to 30,000 people (as of 2007). The president of the Kennesaw Historical Society had this to say about their pro-gun town: “People in Europe feel they need to be protected by the government. People in the US feel they need to be protected from the government.”

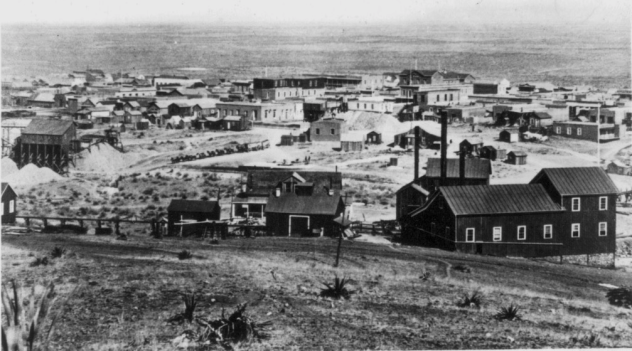

4 Gun Control In The Wild West

Listen to someone like Rick Santorum, and you’ll hear the opinion that the crime rate of the Wild West was low because everyone had the right to bear arms. That wasn’t exactly the case. He’s partially right; records show that the murder rates in some of the most notorious of the Wild West cattle towns, like Tombstone and Deadwood, only averaged about two per year. Mining towns, like Bodie, California, boast a contrasting rate of murder by gun of about 29 per year. (That’s proportionately higher than 1980s Miami.) So, what’s the difference between the cattle and mining towns? Cattle towns like Tombstone had a strict no-guns-allowed policy. In fact, a fine levied against certain people for wearing their guns into town illegally is what kicked off the infamous OK Corral gunfight. And we all know how that one ended. Technically, most of the cattle towns let people wear their guns in, but their first stop had to be the town’s main hotel or the sheriff’s office, where they were expected to check their weapons until they left town again. Other towns, like Bodie, didn’t have the same policy of disarmament and had far more shootings. While that seems to seal the deal for argument that gun control lessens deaths, it’s not that simple. Researchers from Ohio State University did some more digging and found that those who lived in the Wild West had a pretty good chance of being murdered, whether they were in a town that banned guns or not. In Dodge City, which had a ban on carrying guns in town, people had about a 1 in 61 chance of ending up a murder victim. Gun homicides became more rare when guns were taken away, but people still had a good chance of dying of something other than natural causes.

3 A 17th-Century Death Sentence

Some of the earliest gun control legislation in America was written right after the founding of its first colonies. Beginning in July 1619, the General Assembly of Virginia sat down to draw up some of the rules and regulations that the new colonies would be governed by. After five days, they had their statutes. There were around 30 of them, including a provision that made it quite clear that anyone found giving, selling, or trading with a Native American and handing over a firearm, shot, or powder would be hanged as a traitor to his people and to his colony. For some perspective, this was about the same time that Pocahontas was acting as an emissary to the Jamestown colony. She had come into town about six years earlier, five years before the declaration that she had married John Rolfe and was sent off to England as an ambassador for her people and for life in the newly established colony. More telling of what was really going on in the colonies was the rather severe law that absolutely forbade putting guns into the hands of people who had been there before European settlers set foot on the new shores. Even more telling than that was the general opinion of the laws: They didn’t work. There were a couple reasons that even the threat of death didn’t keep early Americans from trading their guns and arming others. It was all but impossible to track and monitor, and the English settlers weren’t the only ones bringing guns to the new settlements. The Dutch and the French were bringing in firearms, too, and had no such severe restrictions, meaning that if the tribes already living there were going to get their guns from someone, it might as well be the new settlers, who took advantage of a lucrative market.

2 The CDC And Gun Research

When it comes to gun control and getting to the root of violence in the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention probably doesn’t spring to mind as being at the forefront of cutting-edge research. But what’s happened with the CDC’s research into gun violence over the last few decades is nothing short of bizarre. In 1996, the NRA accused the CDC of publishing reports and findings with a very specific goal in mind—lending support to gun control. Perhaps not surprisingly, the CDC found themselves on the side of a losing battle. Congress, in an epic, passive-aggressive move spearheaded by the Republicans, cut the CDC’s budget by $2.6 million. Does that seem like a strangely precise number? It’s exactly how much the CDC had spent looking into gun violence the previous year. The CDC clearly got the message and initiated a self-imposed policy of not looking too closely at gun violence. Over the next decade or so, the federal funding that they received for gun-related projects continued to drop, including a 96-percent drop in their funding for work in preventing firearm injuries. They’re not alone, either. There has been a distinct lack of gun-related studies done by organizations like the National Institute of Justice as well, suggesting that the message Congress delivered to the CDC was heard loud and clear by countless public and private organizations. In 2013, President Barack Obama issued a rather direct order to the CDC—to start studying gun violence again. But they haven’t. In the few years following his order, budget requests made by the CDC have continually been declined by Congress. The resulting documentation and research coming from the CDC is pretty odd, and in spite of issuing reports with titles like “Elevated Rates of Urban Firearm Violence and Opportunities for Prevention,” they’re still sticking to the well-known, widely accepted facts while still flying under the radar of Congress—and the NRA.

1 The National Firearms Act And Miles Edward Haynes

In 1938, the US enacted one of the largest, most all-encompassing gun control legislations—the National Firearms Act. The act was brought to the table because of the increased use of firearms in large-scale shootings, most of which came from crimes relating to gangs and Prohibition. The law stated that firearms now needed to be registered with the secretary of the treasury and that the information was transferable to any state government and could be used in prosecution of any crimes. It seemed like a pretty reasonable thing, but it was found to unenforceable and unconstitutional because of a weird loophole that was discovered in 1965. Miles Edward Haynes was charged with possessing an illegal firearm. It was a 410-gauge shotgun with a sawed-off stock, and it wasn’t registered as the National Firearms Act required. He was put on trial, found guilty, and sentenced to four years. The problem was that the Federal Firearms Act of 1938 made it illegal for a convicted felon to own a gun, and when Haynes was arrested for owning the shotgun, a convicted felon was exactly what he was. Registering the gun as he was supposed to would have sounded all kinds of alarm bells, and that would have been in direct violation of his Fifth Amendment Rights, namely his right not to incriminate himself. That made the act completely unenforceable. In 1968, the Gun Control Act sought to rectify the constitutional conflict, adding that it wasn’t required to register a firearm that was already in a person’s possession, and furthermore stating that the registration information was no longer valid to pass along to law enforcement agencies in prosecution of a crime—showing just how complicated the question of gun control can get. Read More: Twitter