An ancient tooth can be used for more than identifying its owner. It can provide a window into a lost world. Teeth reflect lifestyle, diet, and environment, including pollutants, diseases, and also the remedies taken to combat them. For our ancestors, teeth were tools and a front line to the world. Their secrets are legion.

10 The Real Paleo Diet

The Paleo Diet is all the rage these days. But does this low-carbohydrate, high-protein trend actually reflect what our ancestors ate? Rotten teeth among the Paleolithic inhabitants of Morocco’s Grotte des Pigeons suggest otherwise. The culprit: sweet acorns. Dated to 15,000 years ago, the teeth reveal that humans were carb-loading long before agriculture. Over half the individuals from Grotte des Pigeons show signs of tooth decay. Cavities plagued all but three. Previously, experts believed that dental health issues related to cavities emerged with the advent of agriculture around 10,000 years ago. It is possible that the inhabitants of Grotte des Pigeons were the exception rather than the rule as previous studies showed dental disease ranging from 0 to 14 percent in pre-agrarian cultures. Curiously, more than 90 percent of the Grotte des Pigeons remains are missing their incisors, leading many to believe that they were ritually removed.[1]

9 Mystery Ape Of The Ur-Rhine

In 2017, researchers from the Museum of Natural History in Mainz, Germany, announced the discovery of a hominid tooth so ancient that it could shatter the out-of-Africa theory of human evolution. Dated to 9.7 million years, the tooth was unearthed in the ancient riverbed of the Rhine and belonged to an Australopithecus-like species similar to the famous “Lucy.” This “Ur-Rhine” site is a hotbed of fossils that has led to the discovery of 25 new species in 15 years. So far, two mystery ape teeth—an upper left canine and an upper left molar—have been discovered in this 10-million-year-old level of sediment. First unearthed in September 2016, the teeth baffled experts, so they waited a year to release their findings. The implications are staggering. Similar species are known to have lived in Africa. However, these southern analogues would not emerge for another four million years.[2]

8 Secrets Of The Gunk

Earlier this year, researchers compared tooth gunk recovered from Belgium’s Spy Cave and Spain’s El Sidron site to shine light on the lost world of Neanderthals. Analysis of these ancient teeth revealed that the Belgian Neanderthals’ diet consisted heavily of meat from wild sheep and woolly rhinoceroses. However, this was not uniform across the Neanderthal world. The teeth from El Sidron indicated a vegetarian forest diet consisting of mushrooms, pine nuts, and moss. Researchers discovered that shifts in diet reflected different communities of microorganisms in the dental plaque. What’s more, one El Sidron specimen shows evidence of self-medication for a tooth abscess and a parasite known as Microsporidia. Researchers discovered poplar bark, a natural source of aspirin, among the Spanish specimen’s tooth gunk. Evidence of Penicillium in his dental calculus suggests that he may have intentionally eaten rotten, moldy vegetation to access its naturally occurring antibiotic—the precursor to penicillin.[3]

7 Prehistoric Pollution

In 2015, researchers discovered one of the earliest examples of man-made pollution in 400,000-year-old dental plaque. Investigating remains from Israel’s Qesem Cave, they found ancient tartar containing traces of respiratory irritants—most notably, charcoal from indoor fires. Qesem is one of the first known examples of regular use of fire. Blackened soil lumps, charred bones, and a 300,000-year-old hearth attest to the cave’s long relationship with controlled conflagration. Most experts believe that humans first harnessed fire about a million years ago. However, when they began using it regularly for cooking has long been shrouded in mystery. The evidence at Qesem suggests that the practice has been going on for at least 300,000 years. The teeth reveal damage from smoke inhalation that resulted from indoor fires used for daily meat preparation.[4] Progress is a paradox. As technology increased, the air quality of Qesem diminished. Fire came with a cost.

6 Hobbit Teeth

Discovered in 2003, the remains of an 18,000-year-old diminutive hominid from the Indonesian island of Flores have long puzzled anthropologists. Was this “hobbit” a deformed human? Or was Homo floresiensis an unknown species? The answer was in the teeth. In 2015, researchers reported that the hobbit’s teeth were “most similar” to those of Homo erectus. Experts proposed that Homo floresiensis had evolved from larger-bodied H. erectus populations from Java. It is likely that they arrived on the island due to a cataclysmic event—like a tsunami. Isolated on Flores, the modern human-sized H. erectus experienced extreme island dwarfism. Between 95,000 and 17,000 years ago, the hobbits’ approximate average height declined from 165 centimeters (5’5″) to 110 centimeters (3’7″) while their brain capacity dropped from 860 cubic centimeters (52 in3) to 426 cubic centimeters (26 in3).[5] These hip-high hominids lived well into the period of modern man and may have been the last non-human hominid species to go the way of the dodo.

5 The Chompers Of Chaucer’s Children

In 2016, researchers used 3-D microscopic imaging of teeth to determine the diet of English children who lived between the 11th and 16th centuries. Teeth were extracted from 44 children between the ages of one and eight who had been buried within St. Gregory’s Priory and Cemetery in Canterbury. The biological anthropologists discovered that the children were weaned around age one.[6] For the first several years of life, they consumed very simple foods—pap, a simple porridge, and a bread soup called panada. Fruits and vegetables were noticeably absent in this medieval child diet. While bland, the diet lacked processed sugars, thus causing significantly less tooth decay than found in modern children. One of the most intriguing findings was that there were no differences between socioeconomic classes in the children’s diets. Adult diet was determined by social status, but this was not true for youngsters. Poor children ate the same as upper-class children.

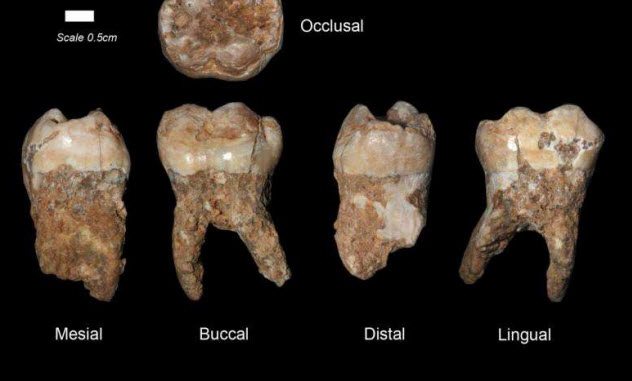

4 Prehuman Dentistry

In 2015, researchers reported evidence of Neanderthal dentistry going back 130,000 years. Using teeth discovered over a century ago from the Krapina archaeological site in Croatia, experts revealed that multiple teeth—including the premolar and M3 molar—showed evidence of manipulation. Grooves, enamel fractures, and scratches suggested use of an ancient toothpick-like device of bone or grass. Experts believe that the breaks occurring unevenly on the tongue side of the teeth suggest that the dental manipulation occurred prior to death. The evidence of ancient dental work at Krapina dovetails closely with other discoveries from the site, such as eagle talon jewelry. This revelation of prehuman body ornamentation sent shock waves through the scientific community, shattering the notion that Neanderthals were artless brutes incapable of symbolic representation. We now know that a Neanderthal would act in the same way as a modern human when faced with objects of natural beauty or dental pain.[7]

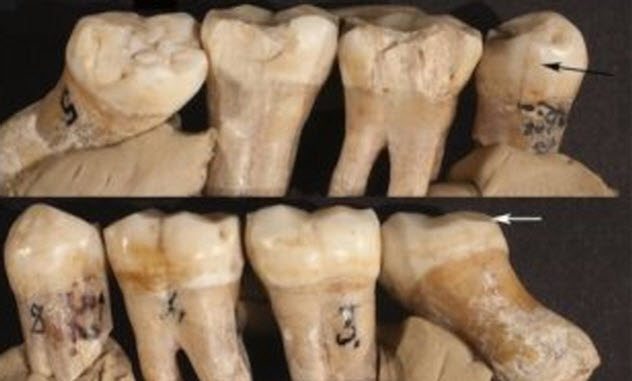

3 Daoxian Teeth

In 2015, researchers discovered modern human teeth in China that are rewriting the story of humans’ conquest of the globe. Discovered in Fuyan Cave in Dao County, the 47 teeth date back to at least 80,000 years ago—more than 20,000 years before humans were thought to have emerged from Africa. The teeth were discovered in the depths of a cave along with the remains of several other species, including an extinct giant panda. As no stone tools have been recovered, experts believe that a predator deposited the remains.[8] According to the researchers, the teeth were too old for carbon dating, so calcite deposits around the finds were used to determine age. The out-of-Africa theory, which predominates thinking today, suggests that humans spread from their ancestral African homeland between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago. The discovery of these teeth opens questions about the time and number of migrations that occurred.

2 Pompeii’s Lovely Teeth

In 2015, researchers employed CT scans to peer into the plaster casts of the victims of Mount Vesuvius’s eruption in AD 79. They were delighted to discover that the people of Pompeii had excellent teeth despite a lack of proper dental care. Not only did they have a diet high in vegetables and fruit fiber without refined sugar, but they also may have been exposed to high levels of fluorine in the air and water due to the area’s volcanic proximity. Archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli invented the technique of plaster casting the Pompeii victims in 1886. It provided a means to move the human remains without risk of degradation. Unfortunately, the technique only allowed researchers to examine the external elements. For 1,900 years, the secrets of the Pompeii victims remained entombed under plaster and ash. However, CT scans changed that by providing a window into a lost world.[9]

1 Mediterranean Missing Link

In 2017, researchers from Germany’s University of Tubingen announced that they had found the missing link—not in Africa but in the Mediterranean. Dated to 7.2 million years ago, Graecopithecus freybergi was an apelike creature believed to be the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Identified from a single tooth and lower jawbone discovered in Greece and Bulgaria, the specimen is hundreds of thousands of years older than similar species known from the East Africa “cradle of humanity.” The teeth of Graecopithecus point to its role as the missing link. Great ape teeth typically have two to three diverging roots. However, the roots of Graecopithecus converge and fuse—just like humans and early hominids. The dating potentially relocates the human-chimpanzee divergence away from Africa to the Mediterranean. Shifting weather patterns, which created grasslands in Europe, may have led to bipedalism and humanlike molars with a wide base and thick enamel.[10] A leading authority on occult music, Geordie McElroy hunts spell songs and incantations for the Smithsonian and private collectors. Dubbed “the Indiana Jones of ethnomusicology” by TimeOut, he is also frontman of the Los Angeles-based band Blackwater Jukebox.