Despite their popularity and usefulness, postage stamps aren’t exactly the most exciting thing in the world. In fact, most people, besides dedicated philatelists, might even consider them boring. But is that really the case? Dig deep enough, and you’ll see that the world of stamps has had more than its fair share of controversial moments.

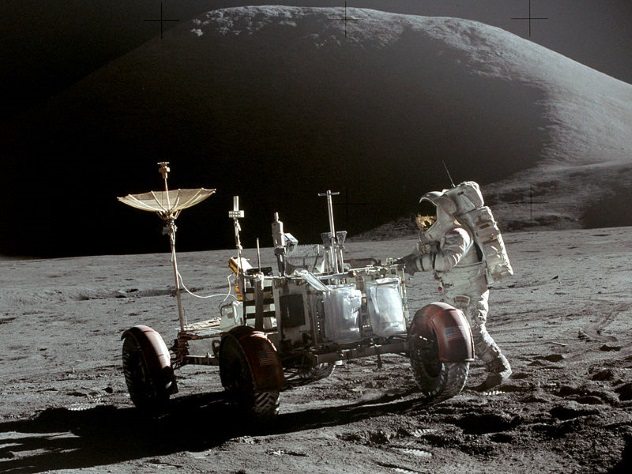

10 Stamps On The Moon

Probably the most famous postage stamp incident occurred in 1971, when the crew of Apollo 15 took hundreds of first-day covers to the Moon without authorization from NASA. According to Apollo 15 commander David Scott, the astronauts were introduced to a man named Walter Eiermann, who, at first, suggested they make some money on the side by signing stamps. Afterward, he went a step further and proposed that the astronauts take 400 commemorative covers to the Moon. They would keep 300 of them as souvenirs while the other 100 went to a German stamp dealer in exchange for a $6,000 trust fund for each individual. The crew agreed, with the caveat that the dealer would hold onto his stamps and sell them at a later date, after the Apollo program ended. This didn’t happen, though, as the dealer put his covers on the market soon after the mission. Technically, the astronauts didn’t break any rules. However, unbeknownst to them, NASA was already in hot water with Congress over the previous Apollo mission. A similar bargain was struck with the Franklin Mint, which involved carrying silver medallions to the Moon and bringing them back to be melted and sold as souvenirs. As a result of this, there was an overreaction to the Apollo 15 incident. Scott said a “witch hunt” ensued and that NASA “hung them out to dry” to appease Congress.[1] None of the astronauts involved went into space again.

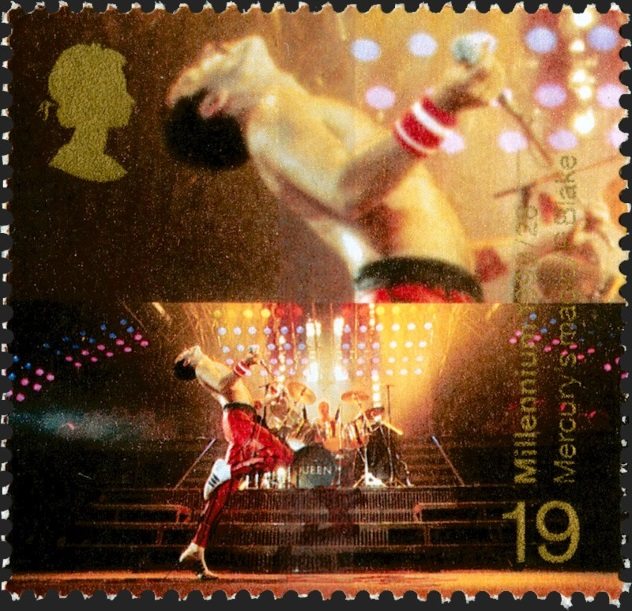

9 Sex, Stamps, And Rock & Roll

A millennium stamp is, as its name suggests, a commemorative postage stamp issued to celebrate the millennium, often depicting notable people or events from a certain country’s history. In 1999, several postal services issued such stamps, including the British Royal Mail. They launched a special series recognizing some of the most notable Britons of the past 1,000 years, divided into subgroups they called “tales.” One of the most notable stamps came from the Entertainers’ Tale, and it depicted Queen front man Freddie Mercury. It was launched in June and caused a stir almost immediately, with many people criticizing the rocker’s appearance. You would assume this happened because people protested Mercury’s lifestyle . . . and you would be partially right. Some people did take issue with that, but far more were angered by a design issue with the stamp itself which broke unofficial guidelines. The Mercury stamp showed the vocalist onstage doing what he did best. However, in the background, you could also vaguely see Queen drummer Roger Taylor. Stamp collectors argued that, according to convention, the only living people who can be depicted on stamps are members of the British royal family. The Royal Mail admitted to a rare rule breach but kept the stamp in circulation, as it had been approved by the queen.[2]

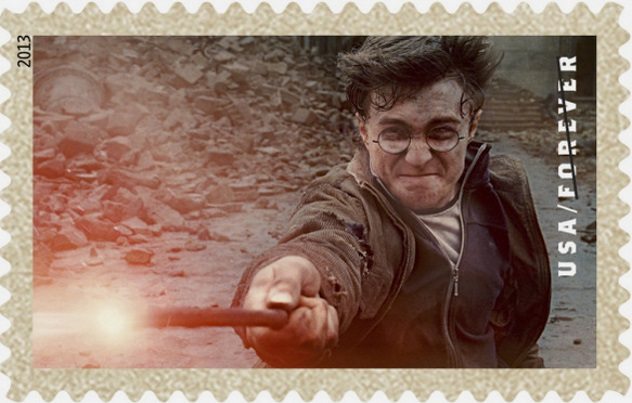

8 Selling Out For Harry Potter

It shouldn’t be surprising to find out that stamps aren’t exactly a hot commodity these days thanks to the Internet. That is why, in recent years, the United States Postal Service (USPS) shifted its focus toward making stamps more commercial in an attempt to boost sales. In 2013, this resulted in the release of 100 million Harry Potter–themed stamps featuring various characters from the beloved franchise. This immediately prompted an angry response from the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC). A division of the USPS established in 1957, the CSAC is a panel which reviews thousands of proposals from the American public for new stamps on a yearly basis and makes official recommendations to the postal service. The group was angry with the decision for two reasons: They did not appreciate the USPS completely bypassing them when releasing the new stamp series. More importantly, they were against using Harry Potter as a theme because it was foreign and was blatantly commercial.[3] They argued that stamps should tell part of the American story, regardless of how well they will sell.

7 Operation Cornflakes

Stamp forgeries were used during wartime as propaganda tools or ways of depriving the enemy of revenue. They were employed during World War II by both sides, most notably by the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Operation Cornflakes. The OSS was America’s intelligence agency that specialized in espionage and subversion. In 1944, they got the idea of dropping letters and other propaganda materials into enemy territory that were so convincing that the German postal service would deliver them to their targets. In order for the plan to succeed, the parcels had to look like genuine German mail. The OSS interrogated POWs who used to work for the postal service in order to get the packaging, sealing, and cancellation markings correct. They had spies collect samples of stamps, mail sacks, and envelopes to duplicate. They used real names and addresses pulled from German telephone directories. Certain stamps, typically stuffed inside the envelopes, were altered to show Hitler’s exposed skull alongside the inscription “Futsches Reich” (“Ruined Empire”) instead of the typical “Deutsches Reich.”[4] The packages were airdropped onto derailed trains immediately following the bombing runs that targeted them. That way, German authorities assumed the letters came off the trains and delivered them without being any wiser about their origins or purpose. The operation took place in the last months of the war. During that time, 20 mail drops were executed, totaling over 96,000 propaganda materials. Although successful from a strategic standpoint, it is difficult to say if Operation Cornflakes had any significant psychological effect.

6 Nobody Wants The Graf Zeppelin

Zeppelin airships were all the rage during the 1930s, at least until the infamous Hindenburg disaster. However, flying a zeppelin, especially over the Atlantic Ocean, was expensive. Travelers paid steep prices to voyage aboard the airship, but a zeppelin could only accommodate 20 to 25 passengers at a time. That is why most of its revenue came from delivering mail. Multiple countries commissioned special postage stamps which could only be used to send mail by zeppelin. They also agreed to give 93 percent of the proceeds to the Zeppelin Airship Works in Germany.[5] At first, the US was hesitant to commit to these terms but eventually conceded, mainly as a sign of goodwill toward Germany. The Graf Zeppelin series came out in 1930 in three variations: the 65-cent, $1.30, and $2.60 postage stamps. The United States Post Office printed one million of each type but was hoping that most of them would be purchased by collectors, thus keeping all the profits. As it turned out, the Post Office overestimated the allure of the stamps and severely underestimated the effects of the Great Depression. At the time, the whole set, which totaled $4.55, was roughly 50 times the price of a loaf of bread. They only sold seven percent of the stamps, and most of the rest were destroyed. This only served to further enrage collectors—they were first angered by the steep cost and later accused the post office of artificially driving up the price by creating scarcity.

5 The Work Of Jean De Sperati

The stamp world is plagued by forgeries. Some of these philatelic fakes are so skillfully done that they fool even the most experienced authenticators. Even among other high-class fraudsters, Jean de Sperati sat in a league of his own. His work was so well-done that even when he presented his stamps as forgeries, experts didn’t believe him. Born in Pistoia, Italy, in 1884, Sperati learned the trade from his mother and two older brothers. He used a common forgery method which involved bleaching genuine, cheap stamps and then creating the image of a more valuable version. Although the British Philatelic Association found out about his forgeries in 1932, they decided to keep the information under wraps in order to avoid damaging confidence in the stamp trade. This lasted for another ten years before Sperati was forced to come clean under unusual circumstances. Living in Aix-les-Bains, the forger sent some of his stamps to a dealer in Portugal. However, his parcel was intercepted by French customs agents, who charged him with illegally exporting valuable goods. An expert valued the stamps at 234,000 francs.[6] That’s when Sperati admitted the stamps were actually worthless counterfeits. Two new sets of experts were brought in, and none believed him until he replicated his own work. Sperati spent the next few years in court proceedings, but afterward, he began selling his stamps as reproductions. They became quite desirable and, in rare cases, were even more valuable than the originals they copied. In 1955, the British Philatelic Association bought out his entire stock and released a booklet of his work titled “The Work of Jean de Sperati.”

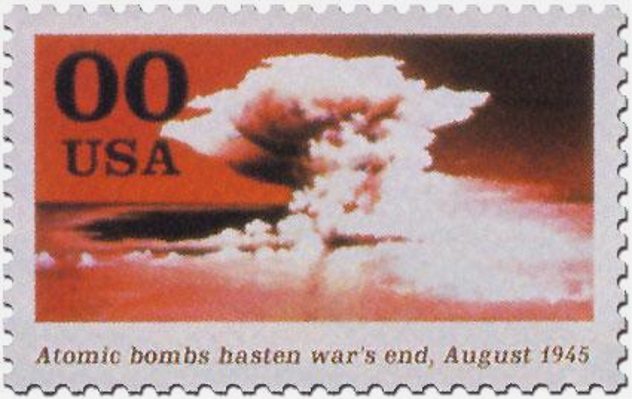

4 Remembering The War

World War II commemorative stamps have occasionally caused controversy due to the nature of the events they try to immortalize. This was the case in England in 1965 with the release of a set of stamps marking the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. There were two issues that people had with the designs. First off, the artist, David Gentleman, initially created the so-called “headless” designs, which omitted the queen’s head from the pictorials because it took up too much space. Other people took issue with a particular stamp which displayed a swastika on the tail fin of a German bomber. In more recent times, the USPS came under fire in the 1990s for the announced release of a stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. It displayed the mushroom cloud following a nuclear explosion with the caption “Atomic bombs hasten war’s end, August 1945.”[7] Many people decried it as insensitive, with the mayor of Nagasaki calling it “heartless.” The stamp threatened to reignite tensions between the United States and Japan. Specific criticism was targeted at the caption, which was seen as justification for the bombing. This was not a universally accepted position, as multiple historians opined that Japan was on the verge of surrender, anyway. The design was reprobated by the White House and US State Department and, in the end, replaced with a portrait of President Truman.

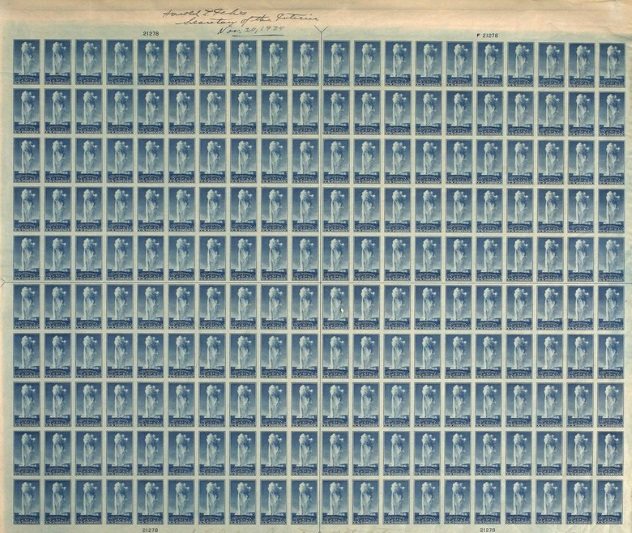

3 Farley’s Follies

American politician James Farley was touted as the kingmaker who engineered four successful elections for Franklin Roosevelt. Among the various positions he held over the years, Farley served as postmaster general between 1933 and 1940. Early on during his stint, he drew the ire of philatelists through a blunder remembered as “Farley’s Follies.”[8] Farley had a habit of taking a few stamp sheets for himself right off the printing press before they were perforated and gummed. He paid for them out of his own pocket, autographed them, and gave them as gifts to friends and family. Eventually, some of these stamps made it onto the open market, and collectors found out about Farley’s custom and decried it as an abuse of power. Even if the postmaster general paid full price for the stamps, the fact that they had his signature and weren’t perforated or gummed significantly increased their value. Since some of them were given to political acquaintances (President Roosevelt included), they could be considered bribes. Protests and charges of corruption led to a congressional investigation. In 1935, Farley found a way to appease philatelists by reissuing all of the stamp sheets in question without gum or perforations, just like the ones he took, in plentiful numbers to meet demand.

2 How Many Treskilling Yellow Stamps Are There?

When it went to auction in 2010, the Treskilling Yellow stamp was described as the most valuable object in the world by weight. We are unsure what that value is, precisely, because on the last two occasions, it was sold for undisclosed amounts. In 1996, it went for approximately $2.3 million. The item traces its origins to 1855, when Sweden issued its first postage stamps, which ranged in denominations between 3 and 25 skillings. The three-skilling stamp was supposed to be blue-green, while the yellow color was reserved for the eight-skilling variant. Somehow, an error resulted in a yellow three-skilling stamp which remained unknown to the public for 30 years. Only one Treskilling Yellow is thought to exist, and its history is well-documented ever since it was discovered in 1886 by a young man in his grandmother’s attic. However, in 2010, a Baron Jean-Claude Pierre Ferdinand Gunther Andre came forward alleging not only that he had nine other examples, but that they had been stolen. The details came to light in a lawsuit filed by the baron and his wife against Clydesdale Bank in London. The claimants alleged they deposited a trunk with the bank in 1986, which they left untouched until 2004. When they finally accessed it, they found the trunk had been broken into, and several items were missing, including rare stamps valued at around $7 million. Most of that worth came from six covers which bore nine Treskilling Yellow stamps.[9] The court dismissed Baron Andre’s claim due to “sheer inherent implausibility.”

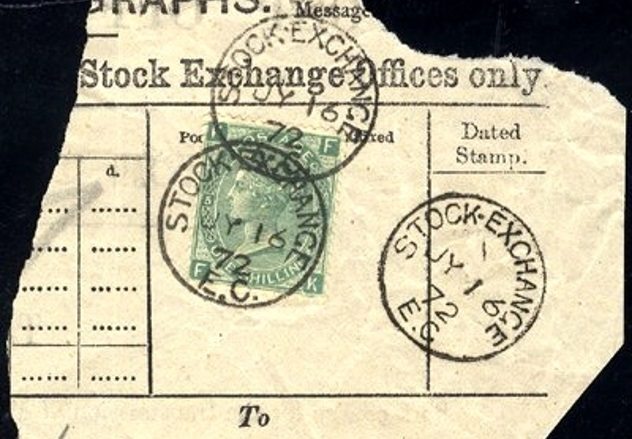

1 The Great British Stock Exchange Forgery

Back in the early 1870s, a group of conniving clerks working for the London Stock Exchange stole an unknown sum of money and got away with it using a scheme which wasn’t discovered for 25 years. The telegraph proved a very useful invention for the Stock Exchange, as it allowed people to dispatch news of the latest stock prices with unparalleled swiftness. When a trader or other agent wanted to send a telegram, the procedure involved filling out a form and affixing one or more one-shilling green stamps to it before submitting it to a clerk. They would immediately cancel the stamp using a dated postmark and send the message. Certain clerks realized they could forge the stamps. That way, they could pocket the shilling without using up the stock of real stamps, which was audited. The counterfeits weren’t perfect, but they didn’t need to be, as they were only briefly handled by the clients, who purchased them from the same clerks shortly before applying them to the telegram forms. These messages were later filed and marked for disposal. The fraud came to light 25 years later and could have remained undetected if all the forms were destroyed as they were supposed to. As it happened, some were disposed of as wastepaper and came into the hands of philatelist Charles Nissen.[10] He was immediately able to spot the fakes, as they had several imperfections and no watermark. To this day, the extent of the deception remains unknown. In one of the recovered lots, inspectors found over 100 forgeries bearing the same postmark date. That would mean a £5 daily fraud, but investigators believe the true haul could have been up to ten times that.