10The Great Bed Of Ware

The Great Bed of Ware was originally built sometime around 1590, and it was first installed in an inn in the town of Ware. The first record we have of it is in the travel records of a German prince who stayed at the inn, which had gotten quite a name for itself thanks to its massive, four-poster bed. The bed was so well known for a very obvious reason that Shakespeare even used it as a rather tongue-in-cheek way to describe something of a huge size. In 1689, the huge bed became even more notorious with the story that it was once host to 26 people—butchers and their wives—although just what went on that night has been lost to history. While that was thought to have been done on something of a dare, its maximum occupancy was usually limited to around four couples. Acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1931 and recently loaned to a museum back in its old hometown, the Great Bed of Ware wasn’t just another bed—it was a tourist attraction. The entire thing is covered with elaborate carvings of leaves, animals, and other designs typical of the Elizabethan period. Along with those are carvings of the initials of the people who slept in the bed during the centuries it was in use. The bed’s designs are scarred by declarations of love we’d recognize today, and parts of it are still smeared with the remains of red wax seals left behind by amorous couples. The Great Bed of Ware was first given its official name by Ben Jonson and is still popular among tourists.

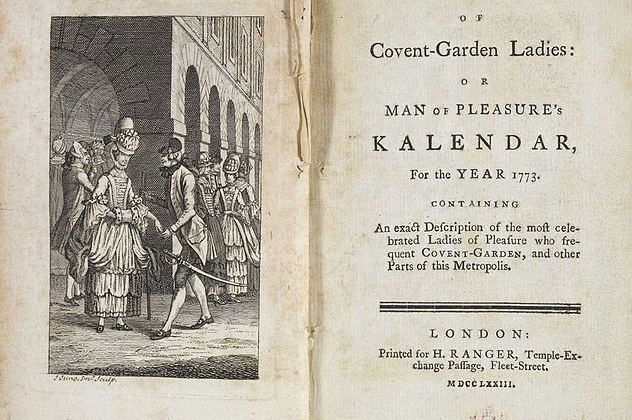

9The Guidebooks To Nighttime Entertainment

London has always attracted people from all over the world. Today, we can hop online and find out everything we need to know about what we want to do while we’re there, but in the 18th century, they needed something a little more low tech. The result was a series of guidebooks that would give the visiting young man all the information he needed to make an educated choice about which lady he was going to spend his evenings with and his money on. Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies was one of the most popular guidebooks, selling thousands of copies every year. The book featured reviews of the different ladies that were up for hire, told what their specialties were, what they were—or weren’t—willing to do, and it even told which ones should be steered clear of, as they were likely to be carrying some kind of disease. The book didn’t pull any punches and gave pretty straightforward assessments, like that of Miss Emma Ell-tt of Gray’s-Inn-Lane. The book stated that she was very attractive . . . until she spoke, at which point “she pours forth such a torrent of blackguardism that shall destroy every attracting feature.” It went on to say, “Our damsel is therefore the most agreeable looking girl when asleep.” Harris’s wasn’t the only book out there, either. There was also Swell’s Night Guides, which described the best places to find prostitutes (as well as reviews of pubs and nightclubs), and it also gave the addresses for “introducing houses,” which were usually labeled as something more innocent for the uninitiated. Behind the sign for the dressmaker or the doctor were houses where the lonely could knock on the door and be matched with a woman for the night. And, if that wasn’t your thing, the book also specified which clubs would allow you behind the scenes to meet the dancing girls. Unfortunately, there aren’t many copies of the books left—they were meant to be used, after all, not saved.

8Elizabeth Needham

While the term “risque” might have a certain connotation, it definitely doesn’t always mean the stories have a happy ending. One of the most famous—or infamous—brothel madams of the 18th century was Elizabeth Needham. While most respectable brothel owners and prostitute-keepers valued experience, Mother Needham valued something else: virginity. Her preferred method of recruitment turned into something that was universally disdained once it came to light. She’d scope out all the coaches that were bringing in young girls who had come to London to seek their fame and fortune, and she would approach them with an innocent offer of work. It was only when she had taken her pick of the prettiest girls and returned them to her brothel that she revealed what she really did, and there’s no doubt that quite a few girls found their innocence ending thanks to Mother Needham. Needham catered to a certain class of people that included members of the military and of the aristocracy. But when it was decided that London was due for a spring cleaning in 1731, her brothel was raided. Mother Needham was arrested and ordered to spend two sentences standing in the pillory of Park Place. She only made it to one. When her sentence was amended to not stand in the pillory but to lie in front of it, she was confronted with a crowd that was livid about the way she’d been recruiting her girls. It was a crowd that was also armed with bricks and rocks; she was stoned, and she died of her injuries on May 3, 1731.

7One Of The First Comics

Mother Needham was also the inspiration for what became one of the first examples of a story told in pictures—the early comic strip. The 1730s marked something of a turning point in the way in which prostitutes were viewed in London. Prior to the crackdown on prostitution, they were often seen as jaded, morally corrupt women, and after the 1730s, there was a gradual swing toward their depiction as women who had fallen into the life because they had no other choice. When William Hogarth published A Harlot’s Progress, he was telling the story of one of these later types of women. The work, which tells the story of Moll Hackabout in six scenes, begins by showing the scene we just talked about—a young, innocent country girl, just arrived in London, is approached by Mother Needham. Ending up the kept woman of a wealthy Londoner, the rest of the work shows her fall to the level of common prostitute, her confinement to prison, and her ultimate death from a venereal disease. A Harlot’s Progress wasn’t just a popular social commentary; it also meant that Hogarth was ultimately credited with bringing the idea of captioned prints that told a complete story into the modern era. The newly found status of this burgeoning art form is one that we recognize today—a credible storytelling medium that’s not quite traditional art and not quite traditional literature, but something in between.

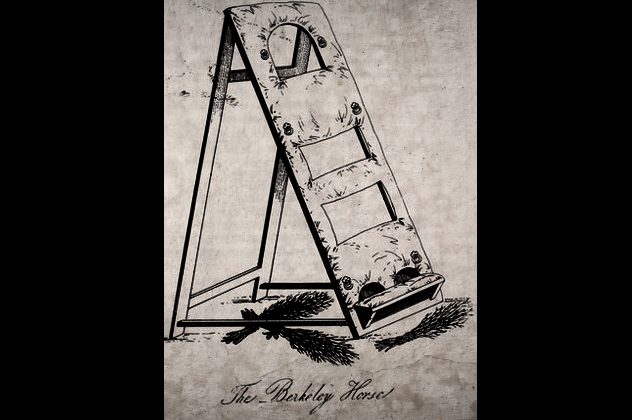

6Theresa Berkley And The English Vice

BDSM has recently been thrown into the spotlight with books and movies that attempt to make it more mainstream, but it’s definitely nothing new. In Victorian England, the practice of flagellation was so common that it even had a name—Le Vice Anglais, or The English Vice. Many of the brothels of London weren’t just your ordinary, run-of-the-mill brothels; instead, they came complete with whips and birch branches. The evolution of flagellation is a strange one. It’s thought that what started out as a religious punishment branched out to become the punishment of choice for school-age children, and when those children grew up, it became something much more erotic. Rather than being an era where people were sexually repressed, the Victorian era—and Theresa Berkley—started an era of BDSM. It was such a lucrative trade that Berkley became known as one of the premiere specialists in flagellation, running a specialized brothel from her establishment at 28 Charlotte Street, Portland Place. Reviews of her place talk about her varieties of whips, the birch branches that she always kept wet and pliant, and the tools with which she could work the skin of even those people who had grown callouses from years of being whipped. Berkley is also credited with the creation of the Berkley horse (pictured above), a particularly long-lived example of her innovative tools.

5Teresia Phillips’s Apology

When Teresia Phillips wrote and released her serialized autobiography, it made a lot of people very nervous. She was one of the most notorious—and prolific—courtesans of the early 18th century, and the book was called An Apology for the Conduct of Mrs. T.C. Phillips, which is one of the most epically passive-aggressive titles we’ve ever seen. The contents had the potential to be so scandalous that no respectable publisher would touch it, and she was forced to print and distribute it herself. Released in several parts, it detailed things like the likes and dislikes of her favorite rakes—including information on which men preferred married women, who could use their marital status to escape the disgrace of an accidental pregnancy. The first volume was released in 1748, and by then, she had several decades of living and prostituting to draw from. One of the first people named in the book was the man who would become the Earl of Chesterfield, whom she accused not only of liking young virgins, but of keeping her as his mistress when she was little more than 13 years old, taking her virginity by force. Over the next few years, she told about her illegal marriages, the men who spent money on her, and her trips and travels. When she released her autobiography, she also took advantage of her reputation to cement her foothold in a very particular field: the establishment of a reputable sex shop. Called The Green Canister, it was set up in what was then Half Moon Street (now Bedford Street) in the notorious Covent Garden. Unfortunately, there aren’t any stock records left, but we do know that she hired some young boys to hand out printed advertisements for her wares. These included condoms made from sheep intestines, which were also distributed in bulk to area brothels.

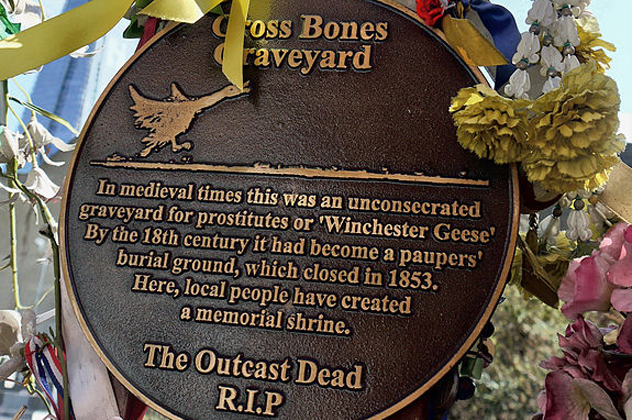

4The Winchester Geese

In death, the women who were known as the Winchester Geese were denied the right to a church burial. Instead, they ended up in unconsecrated ground and in places like Cross Bones Cemetery. But in life, they had something of an odd, almost religious aura. Covent Garden wasn’t the only place in London associated with some of mankind’s baser pleasures; Southwark has operating brothels that dated back to Roman and Viking occupations of the area, and by the time London Bridge was built, Southwark was under the control of the Bishop of Winchester. One of the richest dioceses in England, their wealth was cemented in 1161 with the establishment of 39 rules that governed the work of the area’s prostitutes. These women became known as Winchester Geese because of their pale chests, and they were protected by laws that allowed them to come and go as they pleased, called for worker registrations, and prevented them from working on religious holidays or for free. (If they were caught performing their services for a personal lover, the “fine” was a dunking in raw sewage and banishment from the fold.) Because they were registered workers, that meant they were taxed by the Bishop of Winchester. The church was also the organization that was responsible for enforcing the regulations and getting rich off the girls’ work, but when they died, they weren’t allowed to be buried on church property. The result was something only a little less formal than a mass grave, but bizarrely, not all the names of the women buried there have been forgotten. Recently, excavations have been going on at cemeteries like Cross Bones, and in 2010, the remains of a young woman who died around the age of 19 from advanced syphilis were identified as belonging to Elizabeth Mitchell, who was admitted to the nearby St. Thomas’s Hospital in 1851 and died on August 22.

3The Floating Brothel

At the end of the 18th century, Britain had started shipping its undesirables off to Australia. In July 1789, the Lady Julian was loaded with around 240 of Britain’s female convicts. Ranging in age from 11 to 68, the women were sent abroad with the hopes that they would help populate the new colony. It wasn’t long before things went exactly as you might expect. Most of the women had been in jail for crimes that were then capital offenses, which meant that many were in for nothing more than shoplifting. Once on board and out at sea, the steward of the ship broke their chains and enslaved them in a completely different way. Every crewman on the ship was allowed to take a “wife” from among the lot. John Nichol, the steward, claimed a girl named Sarah Whitelam for his own. She had been convicted of petty theft. The only record we actually have about what went on during the journey comes from Nichol’s own memoirs, and it’s pretty dire stuff. Every time the ship docked at a new port—including Rio de Janeiro and the Canary Islands—they opened the doors and had the women ply their trade. Nichols was thought to have acted as a facilitator, heading out into the city and to other ships to let them know that there were women waiting for sailors that had been out to sea for way too long. We know that there were at least a handful of births on the ship, but we don’t have a lot of names. Whitelam was one of those who gave birth, and weirdly, it was deemed one of the only ways for the women condemned to the life of a pioneer to make enough money to have a chance at something more.

2Holland’s Leaguer

Sadly, a lot of the details of Holland’s Leaguer have been lost, but what we do know is pretty epic. The brothel was one of the most famous brothels of Bankside, run by an enterprising madam named Elizabeth Holland. Far from your ordinary establishment, it was a former manor house completely surrounded by a moat and accessible only via a drawbridge, a feature that would eventually prove useful. The term “leaguer” refers to a military camp, although the brothel was probably only given the name during the winter of 1631–1632, when it withstood a famous “siege.” Local law enforcement had arrived to shut the brothel down and evict the residents, probably after a new landlord purchased the lease. But Elizabeth Holland lured the soldiers onto the drawbridge and then dropped it beneath them, depositing them in the moat. According to the most popular version of the story, they not only ended up taking an impromptu swim, but the women of the brothel took the opportunity to empty all of their chamber pots onto them. Naturally, the authorities weren’t pleased, and Elizabeth Holland was summoned before the infamous court of Star Chamber. Prudently, she seems to have decided to skip town instead. Shortly afterward, the residents of the brothel started a successful petition to get government protection from rioting apprentices who plagued the area every Shrove Tuesday. As part of the petition, they swore that Elizabeth Holland had vanished six weeks ago and nobody had seen her since. Since there is no record of a trial, we can conclude that Elizabeth successfully escaped the long arm of the law. Perhaps she even returned to London and appears in the historical records under a different name.

1Nell Gwyn And Orange Moll

While the vast majority of England’s prostitutes had incredibly hard lives and died young, Nell Gwyn’s story is proof that it’s all about getting noticed by the right people. For the young, low-born girl, it all started when she was selling oranges at Drury Lane. Mary Meggs, otherwise known as Orange Moll, was in charge of concessions for some of the most highly visible theaters of the area and would employ a handful of girls to “sell oranges.” While they certainly did sell fruits and candies to theater-goers, they did much more than that, too. They were often the go-between when wealthy theater patrons needed a way to get messages back to the actresses who had caught their eye. While Orange Moll had troubles that kept her in and out of court, Nell soon caught the eye of actor Charles Hart. It wasn’t long before the little orange seller had become his mistress, and he recognized her for her talents on stage as well as backstage. By the time she was passed along to Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst, Hart had become known affectionately as Charles the First. Buckhurst became Charles the Second, and her Charles the Third? The real King Charles II. Nell was one of at least a dozen of the king’s mistresses, but she had a trait that the others didn’t—the public liked her. By the time she retired from the stage, she was pregnant with the king’s child, whom she managed to acquire a title for in spite of never having one herself. Her methods were simple and straightforward—whenever the king was around, she’d refer to the boy as, “You little bastard.” Needless to say, Charles was a little horrified at this completely accurate name for his son, who was given the title of the Duke of St. Albans. Nell would only outlive the king by a few years, but she also never forgot where she came from. She’s now credited with a plaque in Hereford that names her as the founder of the Chelsea Hospital. Read More: Twitter