The French celebrate Bastille Day with fireworks, military parades, dancing, live music, and food. But while the Bastille itself is long gone, the notorious building is far from forgotten. Here are 10 facts about the Bastille that every lover of liberty should know.

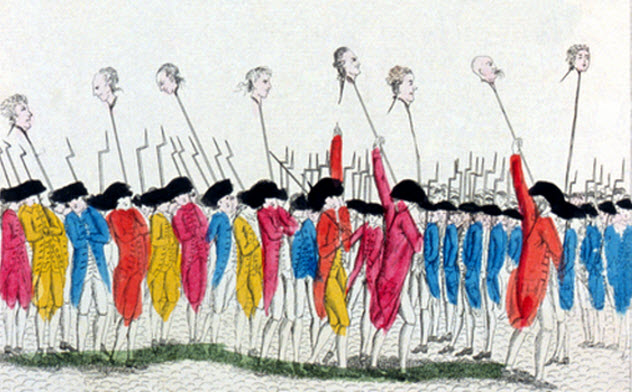

10 The Bastille Only Held Seven Prisoners On July 14, 1789

The popular image of the Bastille as a bastion of tyranny is only partially true. In its heyday, the Bastille was notorious due to the lettre de cachet, a royal order under which those who displeased the king could be locked up indefinitely without a trial. In 1726, for instance, the French philosopher Voltaire was locked up for insulting a powerful young nobleman whose family had the ear of the king. Voltaire was released only after voluntarily agreeing to go into exile in England. Contrary to popular belief, however, the Bastille was not stormed because it was a prison or even a symbol of absolute power. The revolutionaries simply wanted the 250 barrels of gunpowder that had been moved there two days previously from the more vulnerable Paris Arsenal. As it happened, the Bastille at the time held just seven prisoners. Four were forgers, two were madmen, and one was a young nobleman put there by his own family for practicing incest. Rather than freeing him, the mob promptly had him moved to an insane asylum.

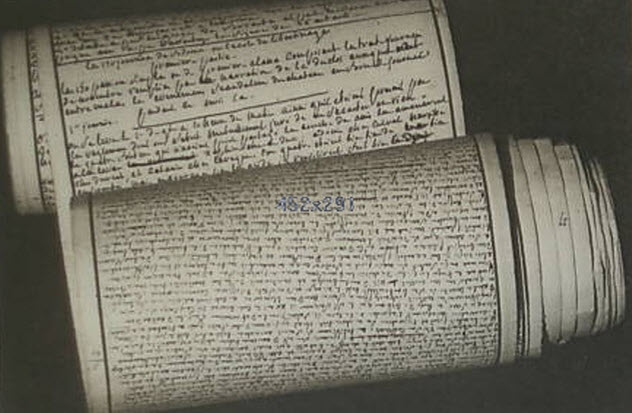

9 The Marquis de Sade May Have Helped Inspire The Storming Of The Bastille

In the weeks before July 14, 1789, the Bastille held one additional prisoner: Donatien Alphonse Francois, better known as the Marquis de Sade. A French aristocrat and author whose name has become synonymous with sexual cruelty, Sade was originally imprisoned under a lettre de cachet issued at his mother-in-law’s request. In April 1789, however, rioting broke out in the neighborhood surrounding the Bastille. When the unrest grew more serious in June, the governor of the Bastille curtailed the prisoners’ daily walks on the towers. Objecting to this further encroachment on his liberties, the Marquis de Sade made a crude megaphone out of a pissing tube. He used it to shout to the people outside the Bastille: “They are massacring the prisoners; you must come and free them.” Rather than let Sade stir up trouble, the governor had him transferred to Charenton in the middle of the night on July 4. Charenton was an insane asylum notable for its relatively humane treatment of the mentally ill. Before being removed, however, Sade had time to hide his recently completed novel, The 120 Days of Sodom. He’d written it in tiny script on sheets of parchment joined together to make a 12-meter (40 ft) scroll. When the Bastille was stormed, the revolutionaries found the novel, which has since become infamous for its graphic depictions of sexual torture and brutality. Sade’s original scroll was recently acquired for almost $10 million by investment fund Aristophil (a company under investigation by French and Belgian authorities for fraud and money laundering).

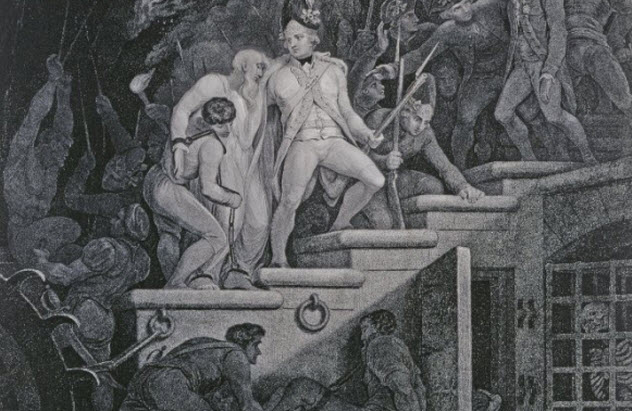

8 The Builder Of The Bastille Was Its First Prisoner

The Bastille started life in 1357 as a fort called the Bastille Saint-Antoine. The word “bastille” itself is a corruption of the French bastide, meaning “fortification.” Over time, the residents of Paris began to refer to the structure simply as the Bastille. In the mid-14th century, France was at war with the English in the Hundred Years War. King Charles V (aka Charles the Wise) decided to turn the Bastille into a massive, eight-towered structure to guard the eastern approach to Paris. Ironically, Hugues Aubriot—the provost (mayor) of Paris responsible for overseeing the building of the Bastille—had the dubious distinction of becoming the Bastille’s first prisoner. Convicted on charges that included heresy and sodomy, Aubriot’s real crime was trying to protect Paris’ Jewish population. Aubriot was given a sentence of death, but the king commuted it to life imprisonment on bread and water. Then, in a move that foreshadowed the French Revolution by 400 years, a mob broke into the Bastille and set Aubriot free. When they asked him to be their leader, Aubriot told them what they wanted to hear—and promptly hightailed it out of town in the dead of night.

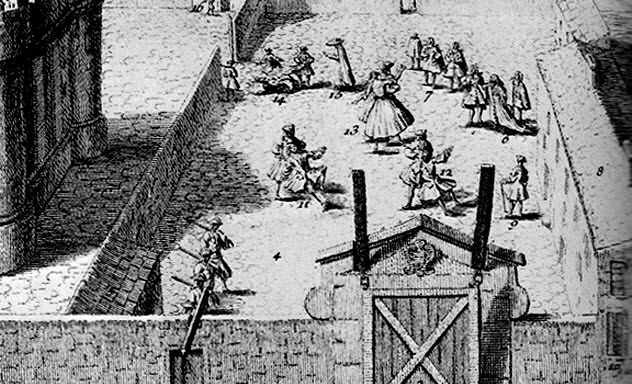

7 People Frequently Drowned In The Bastille’s Moats

The Bastille consisted of eight closely-spaced towers, each more than 22 meters (73 ft) tall and 2 meters (6 ft) thick, connected by curtain walls that were 3 meters (10 ft) wide. The towers had nicknames—often referring to a notable feature or function—such as the Chapel, Treasure, Well, and Corner Towers. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the suburb of Saint-Antoine was built around the prison. The townspeople were permitted to sell their wares in the prison’s outer courtyard. Barbers, cobblers, food sellers, and other merchants plied their trades during the day. People were welcome to come and go at their leisure as long as they didn’t loiter. The outer courtyard also contained a large clock, which was held up by sculpted figures representing prisoners in chains. The entire structure was surrounded by moats, which were originally filled with water from the nearby Seine. There was no railing between the walkways and the moats, and people frequently fell in and drowned. In later years, the moats were dry.

6 Someone Should Have Told Prisoners To Avoid The Basement

Each of the Bastille’s towers had four stories containing suites of rooms approximately 5 meters (15 ft) across and 4 meters (13 ft) high. The top story of each tower had an octagonal room known as a calotte. The height of the calottes diminished rapidly at the sides of the room, making it possible to stand upright only in the center. Worse, they were unbearably hot in the summer and cold in the winter. Other than the calottes, however, the prisoners’ rooms in the Bastille were quite comfortable. They had whitewashed ceilings, brick floors, and large windows, with three steps leading up to each. Each room also had an open fireplace or stove to keep them warm. In the basement of each tower was an underground room. Although we would probably call these the “dungeons,” they were known simply as the “cells” at the Bastille. The cells were damp and noxious and far worse than the calottes. By the late 18th century, use of them had been banned entirely, save when necessary to temporarily restrain insubordinate prisoners. The cells’ grim reputation stems primarily from the memoirs of a tax official named Constantin de Renneville, who’d been imprisoned for 11 years on charges of spying for the Dutch government. He claimed that he had been forced to sleep on damp straw in a bitterly cold, rat-infested cell while being fed only bread and water. However, Renneville’s claims are difficult to confirm. As a condition of being let go, the Bastille’s prisoners were required to pledge an oath of secrecy. It is possible, therefore, that Renneville’s claims were exaggerated, meant merely to shock the public into buying more copies of his story.

5 The Bastille Wasn’t Used For Torture

In the first half of the 17th century, Cardinal Richelieu (on behalf of Louis XIII) turned the Bastille into an official state prison. Prisoners were, for the most part, members of the nobility who had committed high treason, espionage, or other offenses against the king. Despite the ban on speaking about the Bastille, many contemporary accounts of the Bastille have survived. Even the ones that talk about the “cells” contain no mention of torture chambers or “murder rooms.” One prisoner noted: “It sometimes happens that prisoners die in the Bastille by secret means, but the instances are rare.” By the time of the French Revolution, King Louis XVI had explicitly prohibited torture—along with use of the cells—in the Bastille. And when the prison was stormed in 1789, the revolutionaries found no instruments of torture or skeletons or even men in chains. They did find two men in the cells. However, these were the two madmen who had been placed there for their own safety during the raid.

4 Most Prisoners Lived Quite Well At The Bastille

Even destitute prisoners lived well at the Bastille. Rather than clothing and feeding them directly, the king would grant them a pension from which they could buy whatever they wanted. Some saved the money and became quite well off. Others who had more to begin with bought chests of drawers, portraits, desks, armchairs, books, atlases, mirrors, folding screens, and other personal items. The Marquis de Sade added “long and brilliant” hangings to his cell. One 17th-century prisoner founded a library at the Bastille, to which were added books donated by the governors, other prisoners, and a wealthy Parisian who sympathized with the prisoners’ plight. To amuse themselves and decorate their rooms, some prisoners drew designs or verses on the walls with chalk. One painted his walls so artfully that the Bastille’s governor kept changing his room so that he could paint those, too. Most prisoners were allowed to entertain visitors and take walks along the towers. Some were allowed day leave to the nearby town. Many had live-in servants while others kept pets. Prisoners dined with the governor and filled their days making music, embroidering, weaving, or knitting. They also played cards, backgammon, or chess. Some engaged in carpentry. One even had a billiards table in his rooms. Prisoners—including those without money—dined on gourmet food and enjoyed wine, brandy, beer, coffee, sugar, and tobacco. Records for the Marquis de Sade show that on one occasion in 1789, he was served chocolate cream, a chicken stuffed with chestnuts, and pullets with truffles, among other delicacies.

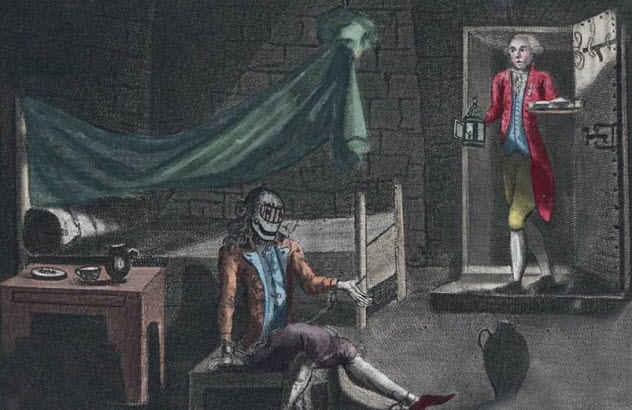

3 The Mask Of The Man In The Iron Mask Wasn’t Actually Iron

The Bastille’s most famous prisoner was the so-called “man in the iron mask.” On September 16, 1698, the new governor of the Bastille arrived with a tall, white-haired man whose face was obscured by a mask made not of iron but of black velvet. The mask left the prisoner’s teeth and lips free, and he was under orders to keep silent and never remove it. He was put in the best rooms the Bastille had to offer, and the guards were ordered to treat him well. However, they were never to let him communicate with anyone either verbally or in writing. Everything that went into or out of his rooms was to be examined for writing—even his dinner plates. If he tried to talk about anything other than his personal affairs, the governor was to threaten him with death. When the man in the mask died unexpectedly on November 19, 1703, following a brief illness, everything he owned was burned. The walls of his rooms were whitewashed and even the floor tiles were replaced, just in case he had found a way to leave writing somewhere. He was buried the following day in the graveyard of the nearby church of St. Paul–St. Louis under the pseudonym M. de Marchioly. Theories about his identity abounded. Some said he was a Marshal of France or Oliver Cromwell. Others thought he might be the playwright Moliere or an unacknowledged twin brother of Louis XIV. The last theory became the basis for the book The Man in the Iron Mask by Alexandre Dumas. A later rumor—most likely spread by Napoleon’s supporters—went so far as to claim that the prisoner had been Louis XIV himself, who had been replaced on the throne by an imposter. According to this theory, the real Louis had married and fathered one of Napoleon’s forefathers while in prison, making Napoleon a descendant of the Sun King.

2 Pieces Of The Bastille Were Made Into Model Souvenirs

By the late 18th century, the Bastille held an average of just 16 prisoners a year, mostly for short stays. That hardly justified the cost of maintaining the structure and its staff, which included doctors, chemists, priests, and a handsomely paid live-in governor. Moreover, due to the growth of the Saint-Antoine suburb, the Bastille’s use as a military fortress was minimal. For these reasons, the government was already planning to tear the Bastille down well before the revolutionaries started the demolition. However, the Bastille was only partially dismantled on July 14, 1789. As a result, the First Republic inherited the problem of what to do with the Bastille. But after the revolution, its symbolic value had changed. Many wanted to leave it standing as a memorial. However, one of the people tearing down the stones on July 14 was the savvy Pierre-Francois Palloy, who owned a construction company. He saw commercial possibilities in the people in the streets below the Bastille asking for stones from the prison as souvenirs. On July 6, Palloy convinced the new assembly to let him demolish the prison. Some of the rubble he carted across town, where it was used to complete the bridge known then as the Pont de la Revolution (today, the Pont de la Concorde). More ingeniously, Palloy also mixed rubble from the stones with plaster and formed it into models of the prison. Some of these he sold. Others he gave away as promotional gifts containing the name of his company. A number of these models still survive and can be seen in museums such as the Carnavalet Museum in Paris, along with the Bastille’s actual steel keys.

1 The Column In The Place De La Bastille Honors A Different Revolution

The bronze column in the Place de la Bastille is known as the “July Column.” It was built to commemorate the “July Revolution” of 1830, the “three glorious days” during which the middle class revolted and forced King Charles X to abdicate. That revolution resulted in the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the king’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, the last king of France. He reigned until another revolution dethroned him in 1848. Today, the column sits on an island in the middle of a busy traffic circle located approximately where the Porte Saint-Antoine stood in the Middle Ages. The names of 504 Parisians who died during the July Revolution are engraved upon it in gold while their remains allegedly lie in four vaults beneath the stone pedestal. The column itself is topped with a Corinthian capital and a gilded bronze statue called the “Spirit of Freedom.” There are no remnants of the actual prison in the Place de la Bastille today. Its outlines are marked in large white paving stones set within the smaller cobblestones in the nearby streets. To see remnants of the actual Bastille, however, you needn’t go very far. While excavating tunnels for the Paris subway, workers found the base of the Bastille’s so-called “Liberty Tower.” They dismantled and reassembled it in a nearby garden to the southwest. The only remaining in situ remnant of the Bastille is a section of the wall, now located on the platform for the number five line in the Bastille Metro station. Jackie Fuchs is a writer, speaker, and attorney whose work has been featured in The Huffington Post and Boing Boing, among others. Her media appearances include Crime Time, CBC’s Q, NPR’s The Madeleine Brand Show, Huffington Post Live, and The Insider. You can read more of her work at https://jackiefox1976.wordpress.com/.